Laura Sangha

This post introduces our new mini-series Visual Culture in early modern England. Guest posts in the mini-series will be published over the course of the next month – we will add links to this page as the post are published. The series celebrates the re-launch of the vital online primary source collection ‘British Printed Images to 1700’. It hopes to encourage use of the BPI archive and to promote conversation about the deployment of visual sources in the study of the past more broadly.

Adam Morton, Printed Images, Laughter and Early Modern History

Helen Pierce, Building Your Own Book: Printed Images, Producers and Buyers in early modern London

Malcolm Jones, Cut, copy, paste: What People Did with Early Modern Images

Adam Morton, Teaching with Early Modern Sources

Something to remember, or more likely forget

In the distant past, time out of memory of man, when I was writing an essay as part of my Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice (teaching training), I spent a week reading lots of articles about teaching and learning History. I remember very little about that immersion in the scholarship, but strangely the one article that stuck around in my mind was a study examining what students remembered about a lecture after they had heard it. The article described an experiment where students were asked to complete a questionnaire about the content of a lecture immediately after they walked out of it, and then they were asked to complete the same questionnaire again, after two weeks had passed.

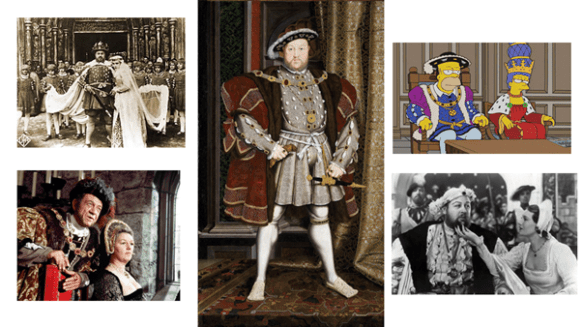

The exact details of the results escape me, but the headlines were relatively pessimistic – students remembered little content, however basic, immediately after a lecture, and this diminished to almost nothing two weeks later. The one exception was that many of them could remember some of the images they had seen in the lecture, and in some cases, why they were shown – i.e. the idea that the lecturer was communicating by showing the image. Ergo: image memory is often superior to word memory.

Theories of cognition come to similar conclusions. According to Allan Paivio’s Dual Code Theory, images elicit words (verbal labels) so that they are stored in the memory twice. By contrast words do not automatically elicit images, a relatively impoverished memory representation that may make the retrieval of words less probable. Though more recent scholarship has nuanced these findings and would allow more scope for varying results according to different learning styles, on average many people retain more from images than they do from texts.

Though it might seem somewhat arbitrary to base one’s practice on a chance encounter with one short, poorly remembered article, I took this to heart. Now I think much more carefully when putting a powerpoint together, whether for a lecture or a research presentation. If audiences are more likely to remember images, then I want my images to contain and convey information alongside the words, I want them to be another form of communication with my audience.

Early Modern Images

Happily, I work on early modern England, a place where the power of images and objects was widely accepted, understood and exploited. Increasingly, scholars of the period are also coming to realise the potential of visual and material culture. The material turn has revealed much about everyday lives and social status in the early modern period, uncovering domestic spaces and places, exploring gender identities, emotions, morality and behaviour, and telling us much about the practice of piety and the experience of life.

More recently Adam Morton’s AHRC-funded project – ‘Integrating the Visual: using printed images in early modern Britain’ – explores how non-textual sources might be further integrated into historical practice. The project considers what visual sources add to our knowledge of early modern Britain. Do they complement our understanding of the period, or challenge it? Do they ask us to reframe existing questions and debates? And what challenges (practical and intellectual) do we face in using them?

British Printed Images to 1700

Adam’s project also secured the future of a vital resource for the study of British visual culture, the British Printed Images to 1700 (BPI) database. The original BPI project ran between 2006 to 2009, led by Michael Hunter. The team worked closely with the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, and the Department of Word and Image at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Software engineering was completed by the Centre for Computing in the Humanities at King’s College London. The website and database were updated, redesigned, and relaunched in last year as part of Adam’s new AHRC project. Software and database design was undertaken by Research Software Engineering, Newcastle University.The BPI database contains almost 11,000 prints and book illustrations. It includes political satires, portraits, maps, landscapes, architectural drawings, playing cards, and titlepages of books, and includes works by the period’s leading printmakers. There are depictions of events, representations of ideas and beliefs and the natural world. There are images of places and activities, and many record the incidental details of early modern life, the clothes, objects, and wares that defined people’s place in their society. The prints have been catalogued using terms derived and adapted from Iconclass and the Library of Congress Subject Headings. They can be searched according to Printmaker, Subject, Person, or Technique.

Research Resources

Not only that, but you will find that the BPI is also home to a range of excellent resources to enhance users’ understanding of printed images and to support research in the field. These include historiographical essays, explanations of print making techniques and technical terms, information about the different genres of print, and biographical information about printmakers. As if that wasn’t enough, a users’ guide will be added soon. In the research section of the site, you can find bibliographies and advice for students intending to work on printed images for their dissertations. Finally, in the Prints in Focus section you can read a series of articles by the printed images expert Malcolm Jones, each dissecting a particular print.

Monster mini-series!

Over the next month, the monster is teaming up with Adam to celebrate the triumphant relaunch of British Printed Images to 1700. Expert posts authored by Adam himself, alongside Helen Pierce and the aforementioned Malcolm Jones will give us an introduction to the abundant, innovative and sophisticated world of printed images in the past. Join us as we try address the question at the heart of Adam’s project: how should images be used by scholars of the early modern period?

Pingback: Printed Images, Laughter and early modern History | the many-headed monster

Pingback: Building Your Own Book: Printed Images, producers and buyers in early modern London | the many-headed monster

Pingback: Cut, copy, paste: what people did with early modern Printed Images | the many-headed monster