This is the second guest post in the mini-series Visual Culture in Early Modern England (read the introduction and find links to other posts here). In this post, Helen Pierce explores the lively world of London print makers and buyers and introduces us to an innovative sales technique.

Helen Pierce is Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of Aberdeen. She specialises in the visual and material culture of early modern Britain, with a particular focus on printed images as vehicles for political engagement.

Helen Pierce

The early decades of the seventeenth century saw the rise of commercial printmaking in England. Previously, both single-sheet prints and book illustrations had been primarily available through trade and exchange, arriving in London from centres of print publishing in the Low Countries, or they were the work of visiting artists, but broader social developments were now informing their production at home.[1]

During the later sixteenth century, London had become a refuge for significant numbers of Dutch, Flemish and French Protestants, seeking freedom of worship following episodes of persecution in northern Europe. Many of these ‘strangers’ brought with them notable skills in creative industries such as painting, goldsmithing, weaving and printmaking, and once permanently settled, children commonly followed their parents into the same sectors. English print sellers were now able to engage directly with professional engravers in London, rather than relying on trade with imported material.

In 1603, John Sudbury and his nephew George Humble established their print selling business at Pope’s Head Alley, just steps away from the commerce hub of the Royal Exchange. John had initially specialised in map publication, and while this continued under his partnership with Humble, they also expanded to printed pictures, both imported and published in London. Sudbury and Humble became well-known for their specialist stock; in 1622 the schoolmaster and author Henry Peacham, who considered himself to have some expertise as a print connoisseur, advised that works by the prolific Dutch engraver Hendrick Goltzius were ‘to be had in Popes head alley.’[2] Here, the customer could also purchase a range of portrait prints engraved by London-based artists including the prolific Renold Elstrack, and from the mid-1610s, Francis Delaram and Simon de Passe. These were primarily half- and full-length representations of monarchs past and present, and other significant figures associated with the Jacobean court and church.

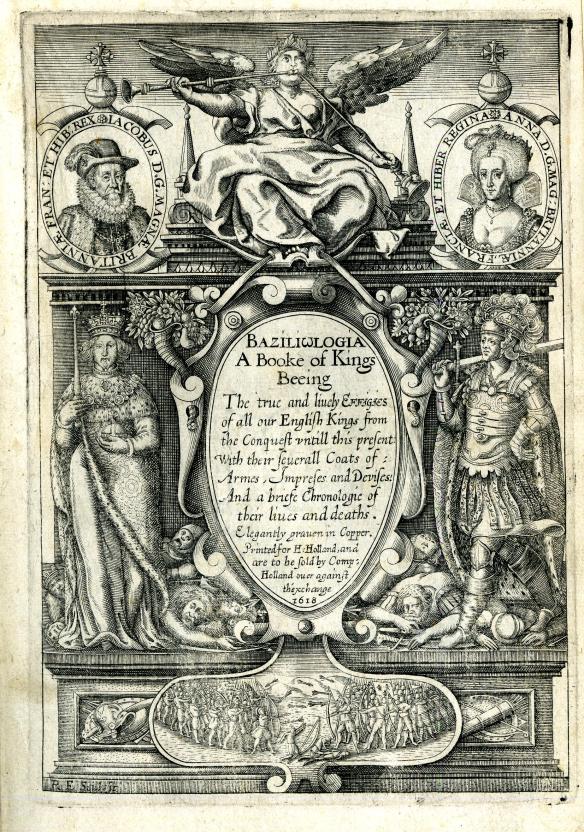

Figure 1: Renold Elstrack, Baziliologia, a Booke of Kings, published by Compton Holland, 1618. Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Sudbury and Humble’s dominance of this new market for printed images was maintained until 1616, when a further family-based print selling business was set up within walking distance of their Pope’s Head Alley premises. At the sign of the Globe in Cornhill ‘over against the Exchange’, publisher and print seller Compton Holland collaborated with his brother Henry, a printer and member of the Stationers’ Company, on a novel and commercially clever project: the Baziliologia. Taking advantage of the broader cultural interest in portraits of monarchs established by Sudbury and Humble, the Hollands also tapped into King James’s own longstanding interest in his personal genealogy; its perceived longevity back to the ancient King of the Britons, Brutus, enhanced his legitimacy as both a Scottish and English ruler.

The Baziliologia, or book of kings, promised to reveal ‘the true and lively effigies of all our English kings from the Conquest untill this present’ according to its title page, engraved by Reynold Elstrack and published by Compton Holland in 1618 (fig.1). This was not an entirely true claim. What is certain is that Holland worked primarily with Elstrack to produce a series of engraved plates, and subsequent prints of twenty individual portraits from William the Conqueror to Henry VII (fig. 2), each approximately 18 x 11.5 centimetres in size. Together, these prints formed a chronological and coherent sequence, with every individual monarch consistently placed within a scrolling frame, furnished with symbols of rule including orbs, sceptres and crowns, while maintaining distinct facial features.

Figure. 2: Attributed to Renold Elstrack, The Most Mighty and Prudent Prince Henry the Seaventh, published by Compton Holland, 1618. Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Accompanied by the title page, these engravings could be bound together as a single volume, but Compton Holland’s clientele also had further options. Together with the title page, each of these images carried Holland’s name and address, implying that they could also be bought separately according to individual choice. There was also a further level of flexibility. At the sign of the Globe, supplementary portraits of more recent monarchs, spouses, and family members, such as Anne Boleyn, and King James’s wife Queen Anna and mother Mary Queen of Scots were also available in the same dimensions as the initial series of kings. This level of choice given over to the print buyer, as to how many portraits they wished to add, or perhaps more practically could afford to add to their personal ‘book of kings’, was a novel commercial element. And not unexpectedly, every surviving iteration of the Baziliologia is different in terms of its contents and level of ‘completeness’: an early modern equivalent of a football sticker album for the seventeenth-century print collector.

Following Compton Holland’s death in 1622 his many printing plates passed into the hands of further publishers and print sellers. Elstrack’s monarchs reappeared six years later as the illustrations to William Martyn’s Historie and Lives of the Kings of England, and Thomas Geele issued his own edition of the Baziliologia in 1630 as a defined set. These subsequent versions were far more stable and complete from the point of sale, with Geele adding an ascending number to each image to reiterate their chronology, and new engravings enabling a complete series as far as Elizabeth I.[3] In contrast, what makes the 1618 Baziliologia particularly worthy of study is its lack of consistency, and in the case of many iterations, the inclusion of additional prints far beyond a line of English monarchs. We can’t be certain of precisely when such additions were made, either during the early seventeenth century or later periods, but they offer a valuable perspective on the historic collecting and categorising of early modern English prints.

A number of expansive iterations of the Baziliologia can be consulted in public collections today, including at the Bodleian Library and Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, the Royal Collection at Windsor and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. However, what appears to have been the largest extended Baziliologia, previously owned and added to by the Delabere family across a century and a half, was broken up and dispersed at auction in London in 1811. The catalogue for this sale details the likenesses of a range of early modern global rulers beyond England and Scotland, with many of them, from Philip III of Spain and Sigismund Báthory, Prince of Transylvania, to the Mogul Emperor Jahangir, engraved by Elstrack and sold by Compton Holland.[4]

Figure 3: Simon de Passe, Matoaka Al[ia]s Rebecca, published by Compton Holland, 1616. Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

In contrast, the engraving by Francis Delaram of Will Somers, Henry VIII’s jester, listed at the Delabere sale and present, like Pocahontas, in the expanded Bodleian Library Baziliologia, is a more curious inclusion. A print of Somers may have been produced and sold in the early seventeenth century simply in terms of historical interest, and the subject’s closeness to his king and court. A further curiosity is Mulld Sake (fig. 4), the depiction of a London chimney sweep sporting an elaborate costume. By the late eighteenth century, this character had become associated with the mythical chimney-sweep-turned-highwayman John Cottington. Mulld Sake is likely to be a satirical commentary on social climbing at the Jacobean court making its inclusion in the Baziliologia all the more interesting; like Will Somers’ portrait, it highlights the shifting rather than static interpretations of a printed image’s content over time.

Figure. 4: Attributed to Renold Elstrack, Mulld Sake, published by Compton Holland, 1616-22. Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Iterations of the Baziliologia which remain intact demonstrate something of the agency of the seventeenth-century print collector in assembling their ‘book of kings’. Yet many collections, like the impressive Delabere volume, fell victim to the craze for extra-illustration, or grangerising, of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, being summarily dismantled and reintegrated into further (scrap)books of biographical history. Engravings perceived to be rare sold for inflated prices. The British Museum’s impression of Mulld Sake, then thought to be unique, was purchased on behalf of the Marchioness of Bath at the Delabere sale for forty guineas, the-then equivalent of almost 300 days’ wages for a skilled tradesperson.[6]

The breaking up and dispersal of such volumes, however, has not been entirely permanent. Today, auction catalogues and printed resources such as Howard Levis’ catalogue of intact and broken up copies of the Baziliologia, have been joined by the ever-increasing digitisation and online availability of public print collections around the world. With a scroll and a click, it is now more possible than ever to reconstruct and reconsider the choices made in the collation of these individualised collections of faces, as we place ourselves in the position of the early modern print peruser.

All images in this post © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

[1] Antony Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain 1603-1689 (London, 1998), pp. 13-14. See also the first volume of Arthur M. Hind’s Engraving in England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Cambridge, 1952-64).

[2] Henry Peacham, The Compleat Gentleman (London,1622), p. 108.

[3] On the complex publishing history of the Baziliologia, see the slightly different interpretation offered by Howard C. Levis, Baziliologia, A Booke of Kings: Notes on a Rare Series of Engraved English Royal Portraits (New York, 1913), Hind, Printing in England, vol. II, pp. 115-120, and Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, pp. 49-52. Levis concludes that the 1618 Baziliologia was made up of twenty-six portraits plus a title page, from William I to James I/VI together with Anne Boleyn and Anne of Denmark. Griffiths’ suggestion that the series ran from William I to Henry VII is accepted here, since it plausibly explains the lack of consistency around the portraits of later monarchs.

[4] A Catalogue of A Most Singular, Rare and Valuable Collection of Portraits… Being the Contents of a Very Celebrated Book That Has Been Preserved 150 Years in the Delabere Family (London, 1811), pp. 39-42.

[5] See, for example, the engraving’s description in the online collection of the National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.77.43.106, accessed 13 October 2024.

[6] British Museum online collection, www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1863-0725-199; National Archives Currency Converter, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter; both accessed 13 October 2024.

Pingback: A new life for ‘British Printed Images to 1700’ | the many-headed monster

Pingback: A new life for ‘British Printed Images to 1700’ | the many-headed monster

Pingback: Cut, copy, paste: what people did with early modern Printed Images | the many-headed monster