This is the third guest post in the mini-series Visual Culture in Early Modern England (read the introduction and find links to other posts here). As in our previous post by Helen Pierce, Malcolm Jones considers how people consumed prints – in this case by adapting them in various ways. Please click on images for enlargements.

Malcolm Jones

In my youth I worked in museums and as a lexicographer, and subsequently until my retirement in 2010, as a lecturer in the English Department of Sheffield University, the year in which my book, The Print in Early Modern England – An Historical Oversight, was published. Since then I have published various articles on early modern prints, and am currently working on a book showcasing the wealth of imagery to be found in early modern alba amicorum (‘friendship books’). These days I do most of my art history informally in maintaining my 100+ Pinterest boards, and exercise my lifelong interest in language in reading the inscriptions on late medieval metal-detectorists’ finds for the British Museum’s Portable Antiquities Scheme.

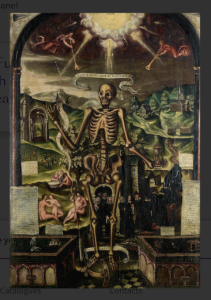

Although unknown to me at the time, just as my book The Print in Early Modern England: an Historical Oversight (London/New Haven, 2010) was going through the press in late 2009, the auctioneers, Bonhams, were selling The Chelsea Collection of Severin Wunderman. I later discovered that Lot 202 was minimally catalogued as a painting on panel, 112 x 77.5 cms., editorially entitled “An Allegory of Death”, described as “English School, circa 1600”, and as “inscribed with various verses from the Bible”. [Figure .1][1]

It was immediately apparent to me that the painting reproduced the entire print known as Death his Anatomy, with the memory of the Righteous, and oblivion of the wicked, in sentences of Scripture,[2] when issued by John Overton in 1669, but that is now only known in the form of four fragments preserved in the British Library, bearing both Peter Stent’s and John Overton’s imprints [Figure. 2].[3]

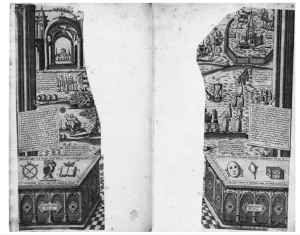

There is no helpfully datable detail on the remaining fragments of this impressively large print (‘royal’ – roughly 520 x 440mm), but we may be sure that it predates Stent’s activity as a print-publisher which began in 1642. That’s because its tombs and the church and funeral procession were cut out of another impression and pasted into one of the concordances compiled by the Little Gidding community for the gospel harmony they presented to Charles I in May 1636.[4] In fact, though not quite the “whited sepulchres” required by the Biblical verse, the two cut-out tomb sides have been butted together and stuck down by their upper edges only, so that they may be lifted up to reveal the skeletons and reptiles inside – and the words of Matthew 23, xxviii: But within full of Deade Mens Bones and of all uncleaneess [sic]. This kind of lift-the-flap paper technology – though here home-made – imitates that of many contemporary continental prints [Figure. 3].[5]

Figure 3: Flap inserted into the gospel harmony presented to Charles I by the Little Gidding community, 1636. British Library C. 23. e. 4.

Thanks to the painting, we can now see that the central skeleton missing from the Bagford fragments holds his dart (by the tip) in his other hand, and stands on a world-orb turned on its side – if not exactly the world-turned-upside-down, then a world decidedly out-of-kilter. A close contemporary parallel is afforded by a French woodcut-illustrated sheet entitled Comment la mort… parle a tous humains [How Death speaks to all humanity…], in which Death stands on the same out-of-kilter world-orb holding his dart in one hand but with which he pierces the globe.[6] Death’s hourglass is a familiar attribute, of course, and its meaning as to the uncertain duration of human life was here underlined by the banderole which – thanks to the painting – we know Death holds in his other hand, reading Watch for you knowe not at what Houre the Maister will come Mat:24,42.

Again, the painting allows us to see that the entire top quarter of the print is missing – the whole of the Heaven section above Death’s head, in which two trumpeting angels flank the irradiated sunburst labelled with the divine tetragram. Their banderols read The memoriale of the iuste shal be blesed P[roverbs]10.7 (left), and The memoriale of the wicked shall perishe Job [18].17 (right). Beneath them, down the respective sides of the print, the just and the wicked are depicted. As is traditional, the righteous are placed on the right hand [of God] (the viewer’s left), and we see them in a state of paradisial nakedness, while on the other side, we witness a funeral procession winding its way towards a churchyard in which a grave is being dug.[7] The tombs are similarly labelled QVIETNES and OBLIVION with appropriate symbols lying on top of each – on the former, positive emblems, a laurel wreath and crossed quill-pens, a helmet above a sword, and a crown and sceptre above a book; on the latter, vanities, in the shape of a mask, a mirror, and a jewel-box.

The fact that the skeleton was cut out of the Bagford impression of our print, and that its tombs were used by the Little Gidding community, demonstrates the importance of the memento mori for early modern English men and women – the ever-present reminders of mortality. It also shows how prints might be ‘sampled’ by contemporary consumers in a way which would horrify us today. Indeed, in the Supplement to her household manual, The Queen-like Closet (1674) [Wing W3287], Hannah Woolley explained how to make a sort of home-made wallpaper, by cutting individual subjects from prints and pasting them onto the wall, and her enthusiastic observation that ‘there is not any[thing] to be named, but you may find it in Prints, if you go to a Shop that is well stored’, is also interesting contemporary testimony to the availability and pictorial encyclopedicity of single-sheet prints in late seventeenth-century England.[8]

Finally, the Wunderman collection panel also points up the fact that early modern English paintings sometimes reproduce English single-sheet prints. To cite just two examples: the extraordinarily violent mass celebrated by the wolf above the slaughtered sheep labelled with the names of the Marian martyrs engraved in 1555 was closely copied on a panel sold at auction in 1980.[9]

Figure 4: John Percivall, An Allegory of the Guy Fawkes Plot, 1630. From Art UK, courtesy of the Warden and Scholars of New College/Bridgeman Images.

And the panel painted by John Percivall in 1630 and presented by Richard Haydocke to New College, Oxford [Figure 4], is copied from The Papists Powder Treason of 1612.

[1] https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/17697/lot/202/?category=list

[2] In the seventeenth century anatomy often means ‘skeleton’ – cf. from Fuller’s Worthies (1662), The anatomy of a man lying in the tombe abovesaid, onely the bones remaining.

[3] Bagford title-pages, British Library Harl. 5916, items 19-22. Alexander Globe, Peter Stent, Bookseller (Vancouver, 1985), *410. A complete impression of the print was advertised for sale in the 1920s in catalogue 244 of the booksellers Pickering & Chatto, though has not surfaced since. P&C cat.244, p.1733, no.11608.

[4] British Library C. 23. e. 4, col.412 and col.75; see Paul Dyck, “A New Kind of Printing: Cutting and Pasting a Book for a King at Little Gidding”, The Library 9 (2008), 306-33.

[5] For which, see Suzanne Karr Schmidt,Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance (Leiden, 2017).

[6] Entitled, “Comment la mort sur le propos de Republique parle a tous humains”[How Death speaks to all humanity on the proposal of a Republic], it is probably a Rue de Montorgueil production though not inSeverine Lepape, Gravures de la Rue de Montorgueil (BNF, 2016). Death is flanked by two allegorical human figures labelled BON ENTENDAMENT and MAL ENTENDAMENT [Good and Bad Intention]. Uniquely preserved in the British Library C.18.e.2[20] ), it is, in fact, part of Marot’s La Deploration sur le trespas de feu messire Florimond Robertet.

[7] The mourning figures emerging from the church to witness the burial suggest the original source print can’t have been any later than c.1600.

[8] Malcolm Jones, “How to decorate a room with prints, 1674”, Print Quarterly 20 (2003), 247-249.

[9] By Christies on 11th April 1980, lot 125.

Pingback: A new life for ‘British Printed Images to 1700’ | the many-headed monster