Our next post in ‘The Voices of the People’ symposium (full programme here) is by Michael Ohajuru, an art historian with an interest in the history of Black Africans in Renaissance Europe. Michael provides us with an example of the considerable potential of petitions as a source for uncovering difficult to find voices in the past, as he dissects a petition sent to Henry VIII by a black trumpter at his court.

Michael Ohajuru

It was my colleague Dr Miranda Kaufmann who introduced me to John Blanke’s Petition to Henry VIII. We collaborated on IRBARE – Image and Reality in Black Africans in Renaissance England, a joint project in which she discussed the lives of over 350 real Africans she had found in the records, while I considered the images of black Africans from the period. The star of our research was John Blanke, the black Trumpeter to the Tudor courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII, as uniquely there is both an image and supporting records of him in the archives.

I was on my way to the National Archive to study a thirteenth century image of a black African in the Archives when I had a call from Miranda. She said she had come across a reference to a John Blake, a trumpeter who had petitioned Henry VIII. His name and function were too close to John Blanke not to consider further. Once at the National Archives I ordered both items. Miranda’s petition came first so I photographed it and emailed the images to her then went off to look at my image. Before I’d completed photographing my image I had an email back from Miranda – she had transcribed the complete petition!

(1)To the kyng our soveraigne lorde

In most humble wise besechethes your hyghnes your true and faithfull servant John Blake oon of your Trompets (2) That where as his wage nowe and as yet is not sufficient to mayntaigne and kepe hym to doo your grace lyke service as other your trompeters doo. (3) It may therefore please your hyghnes in consideracon of the true & faithfull service whiche your servant dailie doeth unto your grace (4) and so during his lyf entendeth to doo to geve and graunte unto hym the same somme/ persome Of Trompete whiche Domynyc desessed late had to have (5) and enioye the said Reward to your said servant from the fyrste day of December last passed during your moost gracious pleasure which wage of xvi d by the day (6) And that this bill signed with your most gracious hand may be sufficient warrant and discharge unto John Heron treasurer of your Chamber for the payment of the said wage accordingly (7) And he shall dailie pray to god for the continuation of your most noble and royall estate longe to endure

Prior to this document we only knew of John Blanke indirectly through references to him in the courts’ household accounts. It is suggested that he came to England in the entourage of Katherine of Aragon in 1501. In 1507 he is recorded in Henry VII’s household accounts by the Treasurer of the Chamber, John Heron, being paid 8 pence a day, playing at Henry VII’s funeral in May 1509 and Henry VIII’s coronation in June of that year. He is depicted in the 1511 Westminster tournament roll where he appears twice. His last mention in the household records is an order in January 1512 by Henry VIII to the ‘great wardrobe’ for him to be given a wedding gift. That is the last reference to him we have in the royal records as he is not found in the full list of trumpeters dated 31 January 1514.

Stephen B. Whatley, Tribute to John Blanke, (2015), Charcoal on paper, A4

Those entries in the court records document facts about John Blanke: nowhere do we hear his voice or gain any sense of the personality behind the name. The petition is as close as we have come to date to having any sense of the man that was John Blanke. For, amongst the conventional language of the sixteenth century petitions written by professional scribes, we can detect the voice of John Blanke – the petitioner.

Giving an exact date to the petition is problematic. We know that both John Blanke and Dominic are recorded in 1509 as playing at both the funeral in May of Henry VII and the coronation of Henry VIII in June so the earliest date of the petition would be Jan 1510 and the latest 1514 when John has disappeared from the inventory.

The text is written in the third person perhaps for some intermediary to stand before the king and read the petition on behalf of John. This petition follows many of the conventions of early modern petitions [which will be described further in subsequent posts], such as opening with a formal acknowledgement of the king and king’s position.

(1)To the kyng our soveraigne lorde

In most humble wise besechethes your hyghnes your true and faithfull servant John Blake oon of your Trompets

John, through the scribe, elevates Henry and belittles himself, clearly establishing the importance of the king as John implores Henry to notice his request. The language is not quite what we would hear if we had met John in the street and asked him to tell us his story. Clearly we do not have power to grant him his wish so he must use appropriate language, addressed to the correct person, in this case the king, if his petition is to have any chance of success.

Here his scribe plays an important role as English was unlikely to have been John’s first language. Further, he probably could not read or write in any language, so he would have been wholly reliant on the scribe to effectively transmit his appeal to Henry using the explicit and implicit conventions and expectations of the day.

Having formally and suitably ingratiatingly introduced himself through the scribe’s conventional opening words, John Blanke then goes through a carefully structured, reasoned argument as to why the king should grant him a pay rise, closing with two conclusions: the first the conclusion of his argument for the pay rise, the second a conventional close from the scribe’s stock endings.

Having considered the formal opening I shall now analyse the petitions contents which opens with John stating his problem:

What is John Blanke’s problem?

(2) That where as his wage nowe and as yet is not sufficient to mayntaigne and kepe hym to doo your grace lyke service as other your trompeters doo.

John’s problem is that he is not being paid enough to maintain the standards expected of him by the king and in comparison with his other Court trumpeters. One can only speculate as to why John’s wages were less than others.

Why should Henry say yes?

(3) It may therefore please your hyghnes in consideracon of the true & faithfull service whiche your servant dailie doeth unto your grace

John deserves more money because daily he gives ‘true and faithful’ service to the king.

Why did he consider his petition reasonable?

(4) and so during his lyf entendeth to doo to geve and graunte unto hym the same somme Of Trompete whiche Domynyc desessed late had to have

John’s logical argument continues as he argues that he should have the same wages that Dominic had before he died, as he is doing the same job as Dominic.

How much does John want and when?

(5) and enioye the said Reward to your said servant from the fyrste day of December last passed during your moost gracious pleasure which wage of xvi d by the day

John is direct as he states how much he wants and when he wants the increase to take effect. He wants his wages to be doubled from 8d to 16d per day and back dated. We know his wages were 8d per day from the Exchequer roll of 1507 which shows the first payment to John Blanke, the Black trumpeter, of 8d per day.

What should Henry do?

(6) And that this bill signed with your most gracious hand may be sufficient warrant and discharge unto John Heron treasurer of your Chamber for the payment of the said wage accordingly

John asks respectfully for the king to sign his petition, in doing so instructing the treasurer to pay him the increase. This is John’s conclusion to his argument for the pay increase.

What does Henry receive for answering this petition?

(7) And he shall dailie pray to god for the continuation of your most noble and royall estate longe to endure

Should the king agree to John’s request than he will daily pray that the king’s reign is ‘long to endure’

Did John receive his pay back dated rise?

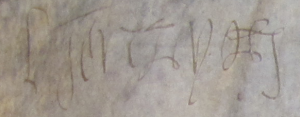

John asked the king to sign the instruction to the Treasurer of the Chamber, John Heron, and the king did just that, as his signature is seen on top left of the petition.

Having considered the petition’s contents and argument I would now like to consider what they might have meant at the time.

The first thing to note is that John was paid wages indicating he was a free man not a slave, like many of those of black African descent in other parts of Europe notably Spain and Portugal, as both had been trading in slaves from sub Saharan Africa since the mid fifteenth century. Further we can infer he was a Christian from his reference to praying for the king.

From the tone and directness of the petition, as he develops his argument we can sense that John knew his value. He considered himself the equal of Dominic so should be paid the same. Henry must have held John in some regard as he gave time to considering and granting his petition. John’s value to Henry’s court is seen not only in the time the king gave to considering his petition but two of his other occurrences in the records.

Firstly, his skill as a trumpeter was valued. As pointed out by Professor Kate Lowe, John stands out on the Westminster Tournament Roll not only on account of his skin colour but his head-gear. While all the other trumpeters are bareheaded John’s hair is hidden out of sight in a multicolored hat. That concession was perhaps on account of his skill that he was allowed this deviance in dress. This is a very rare are case of a black African in Renaissance Europe in a court setting not wearing standardised court attire, indicating his value to the court.

Secondly, Dr Miranda Kaufmann describes when John married in 1512, Henry VIII instructed the great wardrobe in a warrant dated 14 January to deliver to ‘John Blak our trompeter’ a gown of violet cloth and also a bonnet and hat ‘to be taken of our gift against his wedding’. Thus John was valued enough by Henry to be given a wedding present.

However, the ultimate proof of his value was Henry’s signature of approval on the petition!

To conclude, John Blanke’s petition gives us a unique insight into him as a character: an opportunity to hear his voice and understand more about the man and his times, reflecting the importance of petitions in helping us hear ‘The Voices of the People’.

I would like to thank Dr Miranda Kaufmann for her unselfish assistance and support in preparing this post.

Bibliography

Dumitrescu, T., The Early Tudor Court and International Musical Relations (Aldershot, 2007).

Kate Lowe, Thomas Earle (eds), (2005) Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Miranda Kaufmann, Blanke, John (fl. 1507–1512) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2014, (http://www.oxforddnb.com/public/dnb/107145.html accessed 11th June 2015).

Onyeka (2013) Blackamoore: Africans in Tudor England: Their Presence, Status and Origins (Narrative Eye and the Circle with a Dot,

Richard Rastall (1964), ‘The Minstrels of the English Royal Households, 25 Edward I – 1 Henry VIII: An Inventory’ R.M.A. Research Chronicle, No. 4, pp. 1-41

National Archive

John Blanke’s Petition to Henry VIII

TNA, E101/217/2, no.150

National Archive

The king’s Book of Payments

[by John Heron, Treasurer of the Chamber]

E 36/214 f109

The Black Trumpeter at Henry VIII’s Tournament

<http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/early_times/docs/john_blanke.htm>

Westminster Tournament Roll, 1511, College of Arms, London

What a great post and rare find! Please keep posting on this topic as you find more information. Eagerly awaiting your next post 🙂

Hi Sarah thanks for the kind words, I’d love to say the next post is soon but such voices from the archives from this period are rare, but they are there! The search continues….. 🙂

Hi, I’ve come to this post a bit late, sorry! It’s really fascinating, so thank you for sharing. I also just wanted to point out that I’m pretty sure that the word which appears twice in line 5 (once towards the beginning, and again at the very end) is ‘Rowme’, while at the end of line 6 it reads ‘*with* the wage of xvjd’: so could it in fact be likely that John was asking to be given the lodgings which Dominic lately occupied, in addition to the wage of 16d per day which he was by this time already receiving?

Stephanie your observation adds a whole new layer of meaning to the text – more research and more reflection required. Thanks!

I have long had a interest in heraldry, and therefore in the Westminster Tournament Roll. I particularly noticed the trumpet banners, and the black trumpeter. I found out, only recently, that the black man was probably John Blanke.

In the transcription of John Blake’s petition, there are several minor spelling errors. Also, “soveraigne” in the heading, is more likely to be “soverain”. I cannot see “continuation” in the middle of the last line — is it possibly “possession”? These two points might be clarified by looking at other contemporary petitions. “Trompeter” (in the third line) should be “Trompete”. The word “trumpeter”, however spelled, was not generally used at that period. When Shakespeare wrote “Enter herald with trumpet”, he meant “… herald and trumpeter”.

In (4), “to have” should be part of the next clause, i.e, “to have and enioye …”. In (7), there is no suggestion that the prayers depend on a favourable outcome. Also, the inference that John was a Christian cannot be made from the reference to praying. Don’t Muslims pray to God? And, anyway, the last sentence is “a conventional close from the scribe’s stock endings”. Again, this could be checked against contemporary petitions. The hat might mean that he was a Muslim. Is there some religious requirement for Muslims to wear head-gear?

This is my attempt at transcription (to which I have added some commas for clarity):

To the king o[u]r soverain lorde

In moost humble wise besecheth yor highnes yor true and faithfull survante(?) John Blake oon of yor trompetes, That where as his wage nowe and as yet is not sufficient to maynteigne and kepe hym to doo yor grace lyke service(?) as other yor trompetes doo, It may therfor please yor highnes in consideracon of the true & faithfull service(?) whiche yor servant(?) daile doeth unto yor grace and so during his lyf entendeth to doo to ye?e [give?] and graunte unto hym the same Rowme Of trompete whiche Domynyc desessed late had, To have and enioye the said Rowme to yor said servant(?) from the furste day of Decembre last passed during yor moost grac[i]ous pleassr w[i]t[h] the wage of xvj d by the day, And that this bill signed w[i]t[h] yor most grac[i]ous hand may be sufficient warrant and discharge unto John heron tressurer of yor Chambre for the payment of the said wage accordingly, And he shall dailie pray to god for the possession(?) of yor moost noble and royall estate longe to endure

Stephanie Appleton’s suggestion of “Rowme” (room) is quite likely to be correct — but not in the sense of “lodgings”, but “position” or “office” (as in office-bearer — not four walls, a desk, a chair, a filing-cabinet, and perhaps a window). I have seen “room” used in the sense of position/office several times on documents of this period, particularly in reference to positions at the College of Arms. I cannot see any evidence that John was already receiving the wage of 16 pence per day (as Stephanie suggests).

Pingback: Addressing Authority: Petitions and Supplications in Early Modern Europe | the many-headed monster

Pingback: 8 Sites of Importance in the History of Black Music in Britain | Heritage Calling

the trumpeters would have travelled with the king when he was on progress and they were with him in Southampton in 1512-13 when the mayor paid them a fee of 6s 8d. Unfortunately the names of the trumpeters are not listed. I have a database of the people who lived in Southampton between 1485-1603 – now over 20,000 and do have a few named people of colour, though many are referenced in documents without names

Pingback: Decolonising and Black British History: a teaching resource | the many-headed monster

Pingback: Decolonising and Black British History: a teaching resource – Imperial & Global Forum