Jonathan Willis

(For the first, introductory post in the series, click here)

After a brief mid-term hiatus, in this last post marking the publication last month of my latest monograph, The Reformation of the Decalogue, I want to explore the Tenth Commandment.

After a brief mid-term hiatus, in this last post marking the publication last month of my latest monograph, The Reformation of the Decalogue, I want to explore the Tenth Commandment.

Earlier in the series, I talked about the Reformed Protestant renumbering of the Commandments. In brief, Reformers took the traditional Catholic list, made a separate precept out of the injunction not to make or worship graven images, and reduced the number back down to ten by folding the two forms of coveting in the Catholic Ninth and Tenth Commandments (of wives and goods) into a single precept.

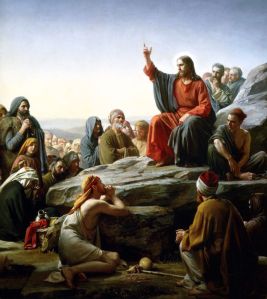

Traditionally, historians have seen the changes at the start of the Decalogue as much more significant than the changes at the end of it. The new Reformed Second Commandment spoke to important concerns surrounding idolatry and iconoclasm – the merging of two forms of covetousness into one commandment was just a case of tidying things up and making sure that there were still Ten Commandments. The historian John Bossy, for example, judged that ‘the exposition of the second table was a less controversial matter than that of the first’.[1] The idea of a commandment that forbade coveting, however, was problematic for Protestant reformers in England (and elsewhere). As the previous posts in this series have shown, Protestant authors already stressed, in line with their reading of scripture, that each commandment already forbade sinful acts not only in deed, but also in word and thought. Expositions of the Seventh Commandment, for example, took their cue from Matthew 5:28, ‘that whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart’. If the Seventh Commandment forbade lustful thoughts towards people, and the Eighth forbade covetous thoughts regarding property, then what was the point of the Tenth Commandment?

The idea of a commandment that forbade coveting, however, was problematic for Protestant reformers in England (and elsewhere). As the previous posts in this series have shown, Protestant authors already stressed, in line with their reading of scripture, that each commandment already forbade sinful acts not only in deed, but also in word and thought. Expositions of the Seventh Commandment, for example, took their cue from Matthew 5:28, ‘that whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart’. If the Seventh Commandment forbade lustful thoughts towards people, and the Eighth forbade covetous thoughts regarding property, then what was the point of the Tenth Commandment?

Even more problematic was the idea that God’s Ten Commandments, his perfect law, could contain repetition or redundancy. Each commandment had to be distinctive, or what was the point of having ten of them?

Reformed Protestants therefore broke new theological ground in their reinvention of the Decalogue, redefining sin itself in the process. Catholic authors explained that actual sin required three elements: the commission of an act that was forbidden (or omission of an act that was commanded); for the act concerned to be against the law of God; and for the act of commission or omission to be voluntary; i.e., for it to have the conscious consent of the will. Without consent, there was no sin: a man who accidentally blasphemed in his sleep had not sinned, because this was an act that could not have involved the conscious use of reason.[2]

Protestants turned this view on its head: man was inherently sinful. All Christians held that children were born with the stain of original sin, the inheritance of the fall of Adam and Even from the Garden of Eden. This was why Catholics felt it was so important to have babies baptised as quickly as possible after birth, for the souls of babies who died before baptism were prevented from entering heaven and were doomed to spend eternity in limbo. Protestant authors held that the stain of original sin – or ‘concupiscence’, to give it its formal name – remained a powerful force in the individual, and was undimmed by the sacrament of baptism.

Protestants turned this view on its head: man was inherently sinful. All Christians held that children were born with the stain of original sin, the inheritance of the fall of Adam and Even from the Garden of Eden. This was why Catholics felt it was so important to have babies baptised as quickly as possible after birth, for the souls of babies who died before baptism were prevented from entering heaven and were doomed to spend eternity in limbo. Protestant authors held that the stain of original sin – or ‘concupiscence’, to give it its formal name – remained a powerful force in the individual, and was undimmed by the sacrament of baptism.

Even more seriously, concupiscence – man’s disposition to sin – was itself an actual, formal sin, and as such forbidden by the Tenth Commandment. Sinful man broke the Tenth Commandment just by being alive – just by having sinful urges, even if those urges were never acted upon, and never received the conscious assent of the will. In redefining the Tenth Commandment, reformers redefined sin, and redefined their view of mankind as an inherently sinful creature from birth to death. This new ‘anthropology of iniquity’ (as I have termed it) was a fundamental part of the theological underpinning of new doctrines such as justification by faith alone, and predestination. These doctrines held that sinful man was incapable of contributing to his own salvation, and that therefore salvation had been ordained by and came directly from God.

The epitome of Puritan divinity, William Perkins, therefore explained in his Golden Chaine that the Tenth Commandment prohibited three things: ‘concupiscence it selfe, namely, original corruption’; ‘each corrupt and sudden cogitation & passion of the heart, springing out of the bitter roote of concupiscence’; and ‘the least cogitation and motion, the which, though it procure not consent, delighteth and tickleth the heart’. ‘And hitherto’, Perkins warned his readers’, we may referre all unchast dreames, arising from concupiscence’.[3] Catholics might be immune from sinning as they slept, but Protestants were not so safe.

The epitome of Puritan divinity, William Perkins, therefore explained in his Golden Chaine that the Tenth Commandment prohibited three things: ‘concupiscence it selfe, namely, original corruption’; ‘each corrupt and sudden cogitation & passion of the heart, springing out of the bitter roote of concupiscence’; and ‘the least cogitation and motion, the which, though it procure not consent, delighteth and tickleth the heart’. ‘And hitherto’, Perkins warned his readers’, we may referre all unchast dreames, arising from concupiscence’.[3] Catholics might be immune from sinning as they slept, but Protestants were not so safe.

English reformers’ worries about, for example, image-worship (or idolatry) did not generally stem from worries about the inherent qualities of images themselves, although some images, such as those of the persons of the Trinity, were forbidden by their very nature. Rather, their misgivings centred around the inability of corrupt humanity to respond to such stimuli in an appropriately godly way. Better to destroy the image than risk its abuse, thereby angering God and plunging the transgressor further into sin. It was the Tenth Commandment, and the new anthropology of iniquity it defined, that underscored such attitudes and behaviours.

[1] John Bossy: ‘Moral arithmetic: Seven Sins into Ten Commandments’, in Edmund Leites (ed.), Conscience and Casuistry in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: CUP, 1988), pp. 232.

[2] Jonathan Willis, ‘Repurposing the Decalogue in Reformation England’, in Dominik Markl (ed.), The Influence of the Decalogue: Historical, Theological and Cultural Perspectives (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2013), p. 193.

[3] William Perkins, A golden chaine: or The description of theologie containing the order of the causes of saluation and damnation, according to Gods word (1600), STC2: 19646, p. 101.

Pingback: Reforming the Decalogue: A Blog Series Preface | the many-headed monster