Our latest Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover post is by Jordan Baker. Jordan concentrates his research and writing on the history of the Atlantic World and blogs about history at eastindiabloggingco.com.

In early modern Europe, people believed in many things that modern readers would find fanciful. One of the most striking examples of this type of early modern thought is the study, and fascination with, monsters. From three-headed beasts to strange creatures of the deep, European audiences readily consumed tales of monstrosity. But what exactly were these monsters?

Occasionally creatures called monsters were exotic species or animals with imposing figures (like whales); sometimes monsters were simply creatures from myth, like satyres or centaurs. Usually, however, what early modern people deemed ‘monsters’ were simply animals or people who suffered from a genetic abnormality.

Seen throughout the Middle Ages, and even into the Renaissance, as acts of God, monsters and monstrous births fascinated early modern Europeans. While some earlier thinkers had attempted to pinpoint what caused the occurrence of monsters, in the seventeenth century at least one author sought an explanation that did not rely on ‘the glory of God.’

Fortunio Liceti and Monsters as Natural Phenomenon

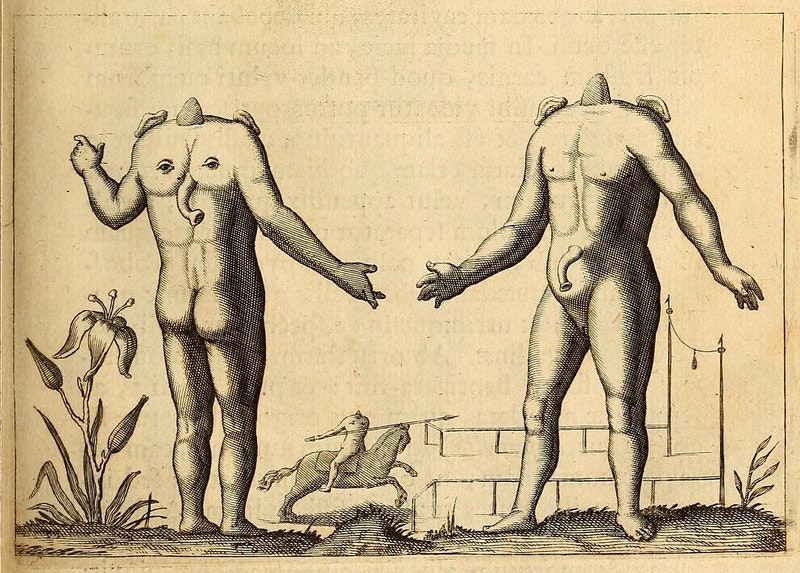

Interest in monsters had been growing for centuries when one of the men most commonly associated with these texts, Fortunio Liceti, penned his seminal work on the topic. While Liceti does not seem to have studied monsters ‘in the field,’ so to speak, he was an avid collector of the illustrations and studies made by others. And though much of his work still included elements that we would consider fantastical, like a headless person with eyes in their shoulder blades, he made the first attempts to categorize monsters as something completely natural.

De monstrorum and the Naturalizing of Monsters

Fortunio Liceti published his landmark book on monsters, De monstrorum causis natura et differentiis, in 1616.[1] The many books on monsters written in Renaissance Europe had all treated the arrival of individuals with genetic abnormalities as a sign from heaven, typically denoting God’s anger over a community’s sinful lifestyle. This tradition kept European intellectuals from seeking alternative explanations, even with the increased interest in natural philosophy that followed the rise of the Renaissance.

Licetit’s work was groundbreaking because he attempted to classify, and thus bring natural order to and systematize, the many types of monsters supposedly witnessed by previous generations.[2]

Liceti’s Monstrous Diagnosis

As the basis for his system of classification, Liceti split monsters into two main groups: “uniform” and “non-uniform.” The uniform category denoted the subject was of a single species and sex, while the non-uniform category meant the subject possessed parts from multiple species or sexes.

From here, Liceti divided the ‘uniform’ category into several subgroups: “deficient” (individuals born without a particular limb(s) or other body part); “excessive” (individuals born with multiple sets of features, for example two heads); “of two natures” (an individual who combined characteristics of “deficient” and “excessive”); “double” (conjoined twins); “extraordinary” (individuals who were considered morphologically normal, but had more superficial abnormalities, like excess hair or skin tone wildly different from their parents); and, finally, “unformed” (individuals born with broken bones, disarticulated joints, etc.).

Some of the illustrations included for the various uniform groups included conjoined twins, an individual suffering from an internal abdominal disorder, and animals born with multiple heads. Given that Liceti felt the need to break down the uniform category into further groupings, but didn’t do the same for the non-uniform category, these types of birth defects may have been far more common. Indeed, all books on monsters from the time included multiple images of conjoined twins, showing the different ways in which individuals could be joined together. Rather than attributing the birth of conjoined twins to the wrath of God or as supernatural omen of some sort, Liceti sought explanations such as the shape of the mother’s uterus as well as complications with the placenta. While modern science has disproved these theories on why these conditions occur, Liceti was the first to suggest purely physiological reasons for their appearance.

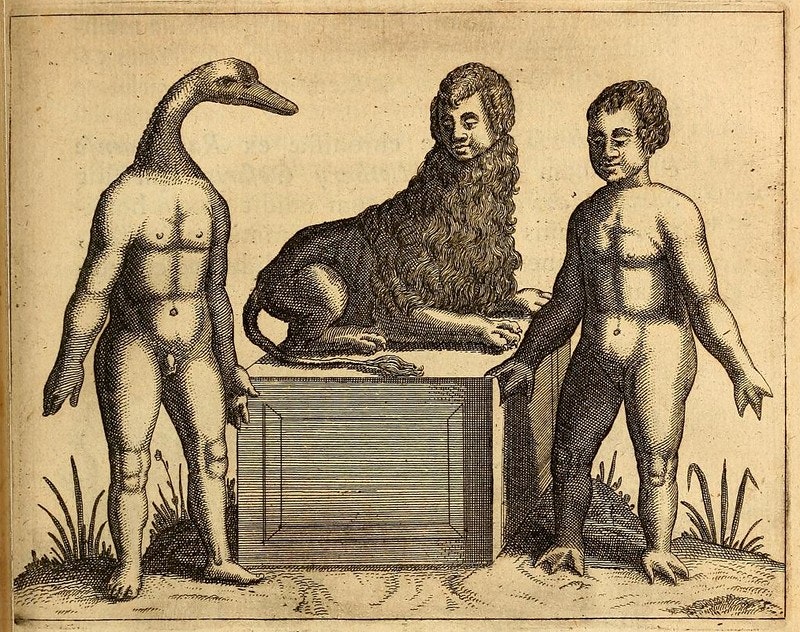

While individuals we would recognize today as inter-sex would have fallen within Liceti’s non-uniform category, when you get into the other half of that grouping, the combined species part, is when things start to get really interesting. Take the image on the left for instance. The boy on the far right seems to have had webbed fingers and toes, a common enough occurrence to not seem all that spectacular (despite the strangeness with which he was drawn). But, as we move to the left, these depictions start to go off the rails. In the middle, we see a lion with the head of a human boy, while on the far left, we see a human body with the head of a duck or goose. Obviously, people like this never existed. This image, and the other fantastical ones included in De Monstrorum, go to show how different early modern European understanding was to modern teratology, or the study of genetic abnormalities.

To Liceti, a monster was “a being under heaven [i.e. not supernatural] which provokes in the observer horror and astonishment by the incorrect form of its members, and is produced rarely, begotten, by virtue of a secondary plan of nature, as a result of some hitch in the cases of its origin.”[3]

For that reason, despite the strange and often fantastical stories from which he derived his studies, Liceti took “Demons and Devils” and “the glory of God” out of the study of monsters, and began to look at them as beings totally of this world. Though the field of teratology did not come into its own until the nineteenth century, Fortunio Liceti’s work is an eye-catching example of the steps European science was taking during his lifetime.

[1] Dunea, “Fortunio Liceti (1577-1657)–Aristotelian Teratology,” Hektoen International: A Journal of Medical Humanities

[2]Bates, “The De monstrorum of Fortunio Liceti,” 49.

[3] Bates, “The De monstrorum of Fortunio Liceti:,” 51.

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster