We are pleased to introduce the latest post in the Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover, by Aaron Columbus. Aaron recently completed his PhD at Birkbeck, University of London and co-edits the blog We Hang Out a Lot in Cemeteries. Aaron’s thesis is focused on the response to plague and the poor in the suburban parishes of early modern London c. 1600-1650. Find him on Twitter @columbus_aaron .

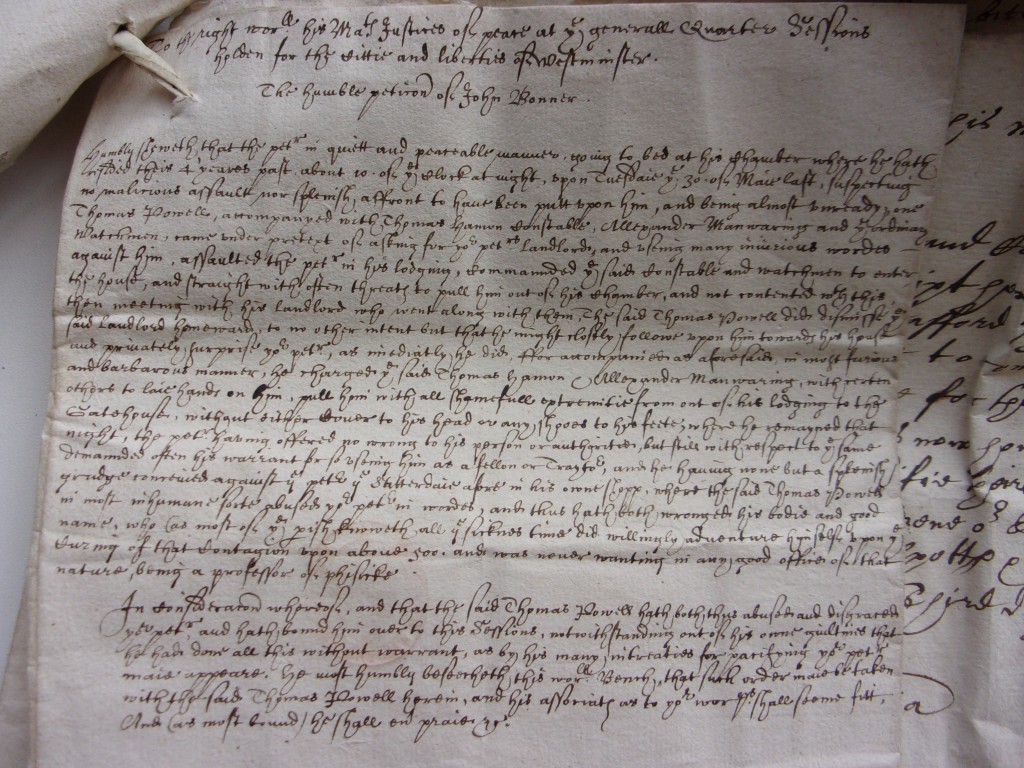

Around ten o’clock on the evening of 30 May 1626 in Westminster, Thomas Powell, accompanied by a constable and watchman, arrived at the door of John Bonner with the pretext of asking for his landlord. Many ‘injurious wordes’ were made against Bonner and he was assaulted in his lodging. Powell, in a most ‘furious and barbarous manner’, then compelled the constable, watchman and others to take him to the local gatehouse.

Bonner gives his account of the incident in a petition to the Westminster Quarter Sessions in 1626, and states that Powell was acting on a grudge that had been conceived against him in his shop the Saturday before the incident. Bonner asked the Justices to take action against Powell and his associates, as he possessed no warrant and had wronged his ‘bodie and good name’. Bonner based this on the understanding of ‘most of the parishe’ that he had, as a ‘professor of phisicke’, willingly worked to cure ‘upon 500’ people of the plague in the 1625 epidemic.[1] Bonner’s petition suggests that the experience of plague might be used as a currency of sorts to further the cause of the petitioner, in much the same way that poverty was made explicit and given focus when seeking poor relief.

The Power of Petitioning project recently published transcriptions for 424 petitions to the Westminster City Quarter Sessions on British History Online. Over 150 of the petitions are dated to the period between 1620 and 1646. These mainly concern petty crime, imprisonment, apprenticeship and poor relief. I was interested to see if plague was mentioned in any of the petitions up to the 1640s.

The invocation of the plague experience, evident in the petition of John Bonner, was a tool used in some capacity by the other identified petitioners. Moreover, the long term problem of plague in London’s suburbs in the thirteen years after the 1636 epidemic is reflected in the petitions, with one lodged in 1638 and four in 1645. So too is the interconnected nature of plague and poverty in London’s growing suburbs. The petitions suggest that during times of plague, the disease might be used in the construction of a variety of rhetorical strategies, to elicit sympathy, establish social standing, or to mark out and remove ‘undesirable’ and vulnerable social groups.

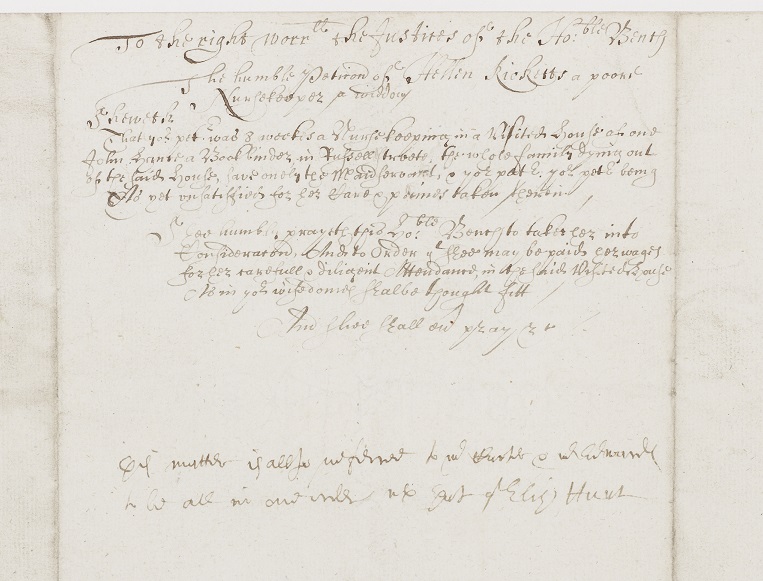

Petitioners might conflate the social problems of plague and poverty to underscore their difficult circumstances and achieve the intended outcome of the petition. John Wilde emphasised his poverty and the great charge of his wife and children and the ‘verie greate hindrance’ he had sustained when his house was visited by plague in 1638. He asked that he be granted a licence to victual in his new dwelling house for the maintenance of his family.[2] Other petitions connect to the poor circumstance of the petitioner and the leading role that women played in seeing the plague regulations implemented. Helen Ricketts was a ‘poor’ nurse keeper and widow in St Martin in the Fields. She worked for eight weeks in the visited house of the bookbinder John Hance in Russell Street. Ricketts and a maidservant were the only survivors of the household’s quarantine. She asked for the unpaid 21s for her ‘carefull diligent attendance’ in Hance’s household.[3]

Others might present the very negative edge of their plague experience to maximise sympathy for their plight and the dangers they had survived. Elizabeth Hunt was a servant in the house of John Alsoone in Crowne Court in St Martin in the Fields. Elizabeth reported in 1645 that the family had all died of the plague. After her sickness in the house and the ‘great danger undergone’ she had been ‘turned out of dores’ and was owed wages for the past year and a half. One of the parish plague examiners had locked up the household’s goods, presumably for decontamination, and she asked that she receive her unpaid wages and the 5s she owed to an apothecary for treatment during her sickness.[4] The shoemaker Richard Pemberton sought sympathy in a bid to reopen his house that had been shut up for seven weeks, to the ‘utter undoing’ of his trade and custom. Pemberton stressed his ‘charity’ in taking in and then finding and paying for lodging elsewhere for a young man that had come sick out of Dunghill Alley in St Martin’s. He complained that his two lodgers had left when the examiners shut his house, and he asked to be free of the ‘insupportable’ charge of the quarantine.[5]

The threat posed to a parish by the non-resident poor might also be connected with the danger of plague by those wishing to remove a nuisance. In 1645, the joint petitioners’ John Battersby and Mary Parker asked for the ‘speedy removal’ of some 60 non-resident Irish poor, which included many newborns, some ‘lame blynde and impotent others sturdy beggers’ in barns and out housing in Ebury Farm in St Martin in the Fields.[6] Endemic plague exacerbated the social stress experienced in the suburbs during the civil wars. Battersby and Parker seem to use this in an attempt to arouse the anxiety of the local authorities by warning that the non-residents were likely to become chargeable to the parish and might increase ‘sicknes’ (taken as plague) and other ‘dangerous consequences’. This can be read as purposeful and aimed at supporting their quest to see the group removed. The elevations in burials above normal levels in St Martin’s in the 1640s and myriad references to plague in the parish sources make clear the ongoing presence of the disease and the more general social pressures managed by the parish. This connects to the timing of the other petitions in 1645.

A search for plague and associated terms in the other county petition sets published on British History Online returns no similar uses of plague in petitioning. Plague is referenced in two petitions submitted to the Worcestershire Quarter Sessions by the Overseers of the Poor and inhabitants of Whitstone, one in 1610 and the other in 1683.[7] The two petitions show the use of plague as a justification for requesting funds for additional poor relief and represent parochial rather than personal interests.

Was the use of the experience of plague by an individual to support the passage of a petition more likely in London’s suburbs? Further work is needed, but this would be understandable in the context of plague as a long term problem in the growing suburban parishes and its intersection with the wider problems of poverty. Plague was a feature of life in London’s suburbs in the first half of the seventeenth century. It makes sense that the experience of the disease might be used like that of poverty in petitioning, and alongside poverty, to impress the validity of the petitioner’s request on the receiving authority.

Further reading

‘Introduction’, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions, 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/introduction [accessed 6 July 2021]

Brodie Waddell, ‘Petitions in Early Modern England: A Very Short Introduction’ (10 June 2019).

References

[1] ‘Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions: 1620s’, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions, 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/1620s#h2-0025 [accessed 11 July 2021].

[2] ‘Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions: 1630s’, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions, 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/1630s#h2-0030 [accessed 11 July 2021].

[3] ‘Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions: 1640s’, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions, 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/1640s#h2-0031 [accessed 11 July 2021].

[4] ‘Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions: 1640s’, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions, 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/1640s#h2-0030 [accessed 11 July 2021].

[5] ‘Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions: 1640s’, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions, 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/1640s#h2-0029 [accessed 11 July 2021].

[6] ‘Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions: 1640s’, in Petitions to the Westminster Quarter Sessions, 1620-1799, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/westminster/1640s#h2-0035 [accessed 11 July 2021].

[7] ‘Worcestershire Quarter Sessions: 1610’, in Petitions to the Worcestershire Quarter Sessions, 1592-1797, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/worcs-quarter-sessions/1610#h2-0001 [accessed 11 July 2021]; ‘Worcestershire Quarter Sessions: 1680s’, in Petitions to the Worcestershire Quarter Sessions, 1592-1797, ed. Brodie Waddell, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/worcs-quarter-sessions/1680s#h2-0017 [accessed 11 July 2021].

Reblogged this on We-hang-out-a-lot-in-cemeteries and commented:

Aaron’s contribution to the #MonsterTakeover from a few weeks back. There are many other wonderful PhD and ECR posts to be explored on their site.

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster