This post is part of the Monster Carnival 2022 – Why Early Modern History Matters Now. Lisa Olson is a librarian and recent graduate of the Master of Information program at Dalhousie University where she completed a thesis focussed on plague publications in seventeenth-century England. Find her on Twitter @Olson_Bochord.

Lisa Olson

Three years since the start of the pandemic seems like an apposite time to see what lessons we can learn about the experience from a closer examination of early modern history. We have seen how widespread illness can effect profound change in society, as it has many times before. We have yet to understand the lasting effects of the current pandemic, however, and may benefit from a closer examination of similar occurrences throughout history.

In 1348, the Black Death reached the shores of England, killing about a third of the country’s population. The plague became endemic, staying in the country for another three hundred years before dying out in the seventeenth century. Outbreaks became less and less common over time and by the seventeenth century, major outbreaks were relatively rare, yet for some unknown reason, particularly severe. There were major outbreaks in 1603, 1625, 1636, and finally, 1665. These instances of plague created circumstances with lasting effects and contributed to immense societal change. One of these changes had to do with the place of religion and medicine in society.

The seventeenth century was a transformative period for England. In addition to civil war, the country was dealing with the aftermath of the English Reformation and the beginnings of a medical revolution. Advancements in print also had significant impact. Texts in England had largely been printed in Latin up until the sixteenth century. The average person, however, could not read Latin and the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw an increase in texts published in English for a general audience.

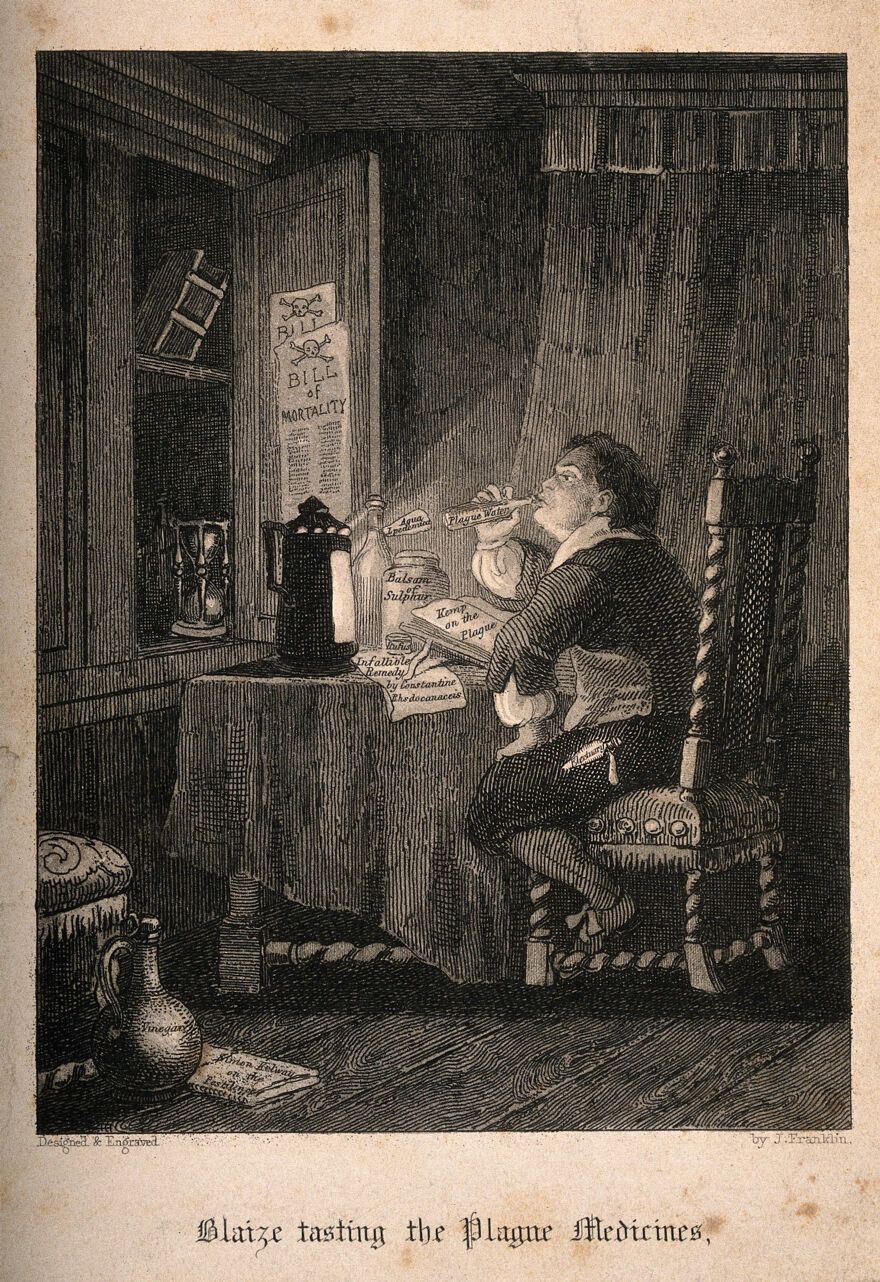

These circumstances led to both the medical and religious sectors publishing an abundance of texts for the public concerning the plague. The Church of England, as well as various religious officials, published an array of sermons and prayers while the Royal College of Physicians, as well as various medical professionals, published medical tracts focussed on the causes, symptoms, and remedies of the plague. While the country had been dealing with plague for centuries, they had never had so many resources available to consult. It was the same disease as previous centuries, but under vastly different circumstances.

Discourse stemming from the realms of religion and medicine often aligned on the most pertinent matters but could differ greatly on the minutiae. For both realms, acknowledging that the plague was an act of God was non-negotiable, as was the view that prayer was the key preventative and remedy for the disease. What was up for debate, however, was what God expected of his subjects. Did he view the use of medicines and preventatives as an attempt to circumvent his will? Or did he expect people to use the herbs, medicines, and physicians, that he created, to keep themselves safe?

Medical texts frequently ascribed the plague firstly, to God’s will and secondly, to natural causes. They believed that it was, in fact, a natural disease which was sent by God, because God controlled the natural world. While prayer was always the first, and foremost, preventative and remedy for the plague, physicians provided people with natural remedies to supplement it. They believed natural remedies to be sanctioned by God. They also believed that God had the final say in someone’s condition, however, for God’s will outranked Mother Nature’s.

Aligning with this messaging, some historians assert that religion encouraged the medical revolution since the plague and the plague’s remedies were both seen to be created by God.[1] Religious publications from this time were not always supportive, however. While religious texts rarely outright opposed the use of natural medicines, many frequently made clear that divine remedies were of primary importance. Natural remedies were often portrayed as ‘permissible’ as a supplement to prayer, but if God decided that it was your time, then nothing would save you – hence the emphasis on prayer. Reliance on natural remedies was often portrayed as foolish and publications from the Church of England in particular frequently belittled the medical profession, fighting against its rising influence.[2]

Authors of medical texts were almost pleading with the public to accept their knowledge while authors of religious texts often took on the role of defending the position of religion in society. The government supported the rise of medicine in their publications surrounding the plague, however, as did many of the people who were desperate for anything to supplement their use of prayer in staying the disease.

Whether through reading or word of mouth, these religious and medical opinions reached the masses who were forced to make their own decisions on matters of the divine versus the natural. With their own lives and those of their families at stake many admitted medicine into their lives. While religion was never going away completely, its influence in society declined as that of medicine rose.

The ways that the religious and medical sectors responded to outbreaks of plague in the seventeenth century led to remarkable changes within and between the two realms. Society was permanently altered. And for all we know, something similar may soon happen again.

[1] Andrew Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550–1680 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 31; Ian Mortimer, The Dying and the Doctors: The Medical Revolution in Seventeenth-Century England, Studies in History: New Series (Woodbridge, UK: Royal Historical Society, 2009), 208; Lucinda McCray Beier, Sufferers & Healers: The Experience of Illness in Seventeenth-Century England, Social History Series (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987), 154–55.

[2] Lisa Olson, “Plague Discourse: Political, Religious, and Medical Publications in England, 1603–1666,” Master’s Thesis, Dalhousie University, 2022, 143, https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/handle/10222/81552.