This post is part of our ‘The People and the Law‘ Online Symposium, a series exploring early modern English – and now Welsh – legal sources. Angela Muir is Lecturer in Social and Cultural History and Director of the Centre for Regional and Local History at the University of Leicester. Her research focuses on gender, sex, crime, deviance and the body in Wales and England in the long eighteenth century. You can find her on X @DrAngelaMuir and Bluesky @drangelamuir.bsky.social.

Angela Muir

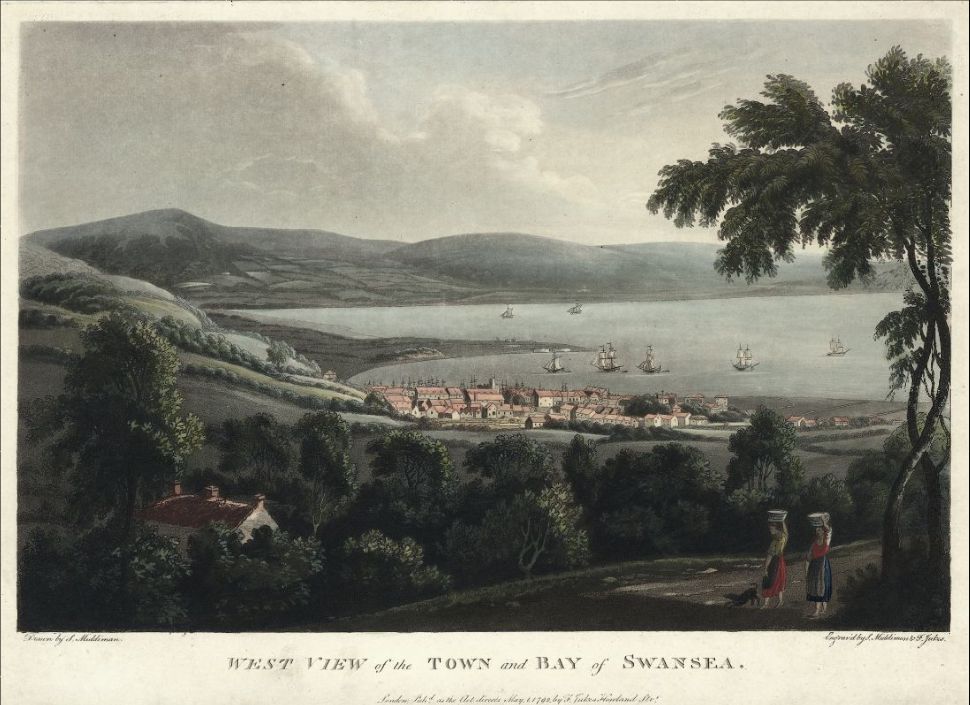

When we think about religious diversity in Georgian Wales, what typically comes to mind is the growth of Protestant Nonconformity. What we don’t typically think about is Judaism. However, Wales was home to a small but important Jewish community from the middle of the eighteenth-century, which was based primarily in the South Wales port of Swansea.

We know much about the Jewish community in Wales in the nineteenth century due to a richer and more varied range of records available, and to the work of historians like Harold Pollins, Ursula R. Q. Henriques and Cai Parry-Jones.[1] Little research has focused on the lives and experiences of the individuals who made up the earlier community. However, through my research using the records of the Court of Great Sessions in Wales, I have serendipitously come across additional evidence which helps add more depth and detail to our understanding of the lives and experiences of some Jews in Georgian Wales.

The Great Sessions were the highest court in Wales between the 1540s and 1830 when they were abolished and replaced with the Assize system. Overseeing both civil and serious criminal cases, the Great Sessions administered English law in Wales. Surviving records from the Great Sessions, which are held at the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth, provide uniquely detailed evidence not only about crime and deviance, but also about Welsh society and culture that historians can uncover by reading these records ‘against the grain’. It is in these records that we find evidence about Wales’s early Jewish community.

Tradition has it that Jews began to settle in Swansea in the early eighteenth century. The earliest individuals who we definitively know about include David Michael, who became a leader of the local Jewish community. Michael is believed to have arrived in Swansea along with a handful of other Jewish men in 1740s, likely as refugees from Germany

By the 1760s there was enough of a Jewish presence in Wales to warrant the establishment of a Jewish burial ground, and in 1768 David Michael signed a 99-year lease with the town council for such a site. This date is commonly taken as the formal establishment of the Swansea Jewish community. In terms of worship, initially the Jewish community is said to have held prayer meetings at David Michael’s house before a purpose-built synagogue was later built.

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales

It is clear that there was a growing community of observant Jews in Swansea from the late eighteenth century onwards. Records from the Great Sessions help to fill in more details about the everyday lives of individuals such as David Michael and the early Jewish community that predates 1768 when the land for the first Jewish burial ground was secured.

For example, in April 1762, a pedlar named Abraham Nathan who resided in Cowbridge, over 40 miles to the east of Swansea, was brought before the Great Sessions on a charge of perjury. [2] Nathan was found not guilty, and really, the details of the case itself are not the most interesting for our purposes here. What is interesting is that the recognisance binding Nathan for the sum of £40 to appear at the next sitting of the court also bound ‘David Michael of the town of Swansea…Hawker and pedlar’ for the sum of £20. What this suggests is that the early Jewish community based in Swansea was not exclusive to Swansea. Connections between individuals spread across south Wales, or at least across the county of Glamorgan, and were developed enough for an individual living 40 miles away to provide surety for another person.

David Michael was named in several other cases, too. From these, we can gain glimpses of his economic activities and hints at his religious life. In 1769, three boys were accused of stealing silver goods from his shop in Wind Street at around 3pm on Friday 29 September.[3] The shop was clearly unoccupied at the time, as one of the boys broke in by prying open a door. The alarm was raised, and a man named Lazarus Moses went and fetched David Michael. When he arrived, Michael confronted the boys about how they had gained access to his shop. One of the boys said he did not know, and then offered to sell Michael some buttons, which Michael recognised as coming from his own shop. Michael also noticed that the boy’s breeches pockets appeared full, and upon inspection, found he had stolen other items including a silver nutmeg grater, looking glass and buckles.

From this case we can get a sense of the type of business Michael was running and items he sold. That his shop was closed in the late afternoon on a Friday suggests the role he played in the religious life of his community. We know that in early days the Jewish community gathered at his home for prayer, so at 3pm on a Friday in September it could very well have been that he had closed up shop to prepare for the start of Shabbat, which would have commenced at dusk that day.

Other examples include a case from 1777, when a young woman named Mary Lloyd stole money from a Carmarthenshire family.[4] Mary then went to ‘Mr Michael the Jew’ and purchased 3 guineas worth of clothes. David Michael’s brother Abraham gave evidence stating that he sold Mary 2 gowns, 2 petticoats, a cloak, some stays, handkerchiefs and stockings. He also engaged in some small talk, asking her where she came from. Abraham signed his name in Hebrew, demonstrating that his Jewishness was very much part of his identity. It is through piecing together fragmentary evidence such as this that we can gain more insight into the lives and experiences of the earliest generations of Welsh Jews. Although it is fragmentary, in reality, the evidence we have of most minority or marginalised groups in the past is always fragmentary. A lack of detailed or plentiful evidence does not mean we should relegate these histories to obscurity. On the contrary, it is the duty of historians to do as much as possible with fragments such as these so that the lives, experiences, and where possible, voices of under-represented groups in the past can be better understood and heard.

[1] Ursula R. Q. Henriques (ed.), The Jews of South Wales (Cardiff: Cardiff University Press, 2013); Harold Pollins, ‘The Swansea Jewish Community: The First Century’, The Jewish Journal of Sociology 1 (2009), 35-40; Cai Parry-Jones, The Jews of Wales: A History (Cardiff: Cardiff University Press, 2017); Neville H. Saunders, Swansea Hebrew Congregation, 1730-1980 (Swansea: Swansea Hebrew Congregation, 1980).

[2] National Library of Wales (NLW) 4/619/5

[3] NLW 4/621/7

[4] NLW 4/624/1

Pingback: The People and the Law: an Online Symposium | the many-headed monster