This is the first guest post in the new monster mini-series Visual Culture in Early Modern England (read the introduction here). To begin, Adam Morton considers what historians should do with the alien and often cruel humour of past ages and in particular the subversive content of satirical prints.

Adam Morton is Reader in Early Modern British History at Newcastle University. He researches the long-Reformation in England, with a particular focus on anti-popery and visual culture. His publications include Civil Religion in the early modern Anglophone World (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) (with Rachel Hammersley), The Power of Laughter & Satire in Early Modern Britain: Political and Religious Culture, 1500-1820 (Boydell & Brewer, 2017) (with Mark Knights), Queens Consort, Cultural Transfer and European Politics, c.1500-1800 (Routledge, 2016) (with Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly), and Getting Along? Religious Identities and Confessional Relations in Early Modern England – Essays in Honour of Professor W.J. Sheils (Routledge, 2012). His current project considers the visual culture of intolerance in early modern England.

Adam Morton

Old jokes unsettle me. Not only because I don’t always get them, but because the ones I do get are often brazenly cruel. They mock, scoff, and jeer at the butt of the joke in a laughter of scorn and humiliation. This cruelty unsettles me because humour is intimate, it speaks to the most human aspects of a culture, the intimate ties, social bonds, and moral norms that glue people into a society. We laugh when something disrupts or breaks those conventions, and laughter therefore takes us close to what made people in the past tick, their assumptions about the world, their emotions, and their view of what was proper.[1]

Laughter, in short, is intuitive, something that Clive James captured succinctly. “Common sense and a sense of humour are the same thing moving at different speeds. A sense of humour is common sense, dancing”. Early modern people? Their ‘common sense’ led them to laugh at rape victims, at the disabled, at those who experienced devastating misfortune, and at domestic violence, among other cruelties.[2] Studying humour takes us closer to early modern people. I am unsettled because I don’t always like what I see.

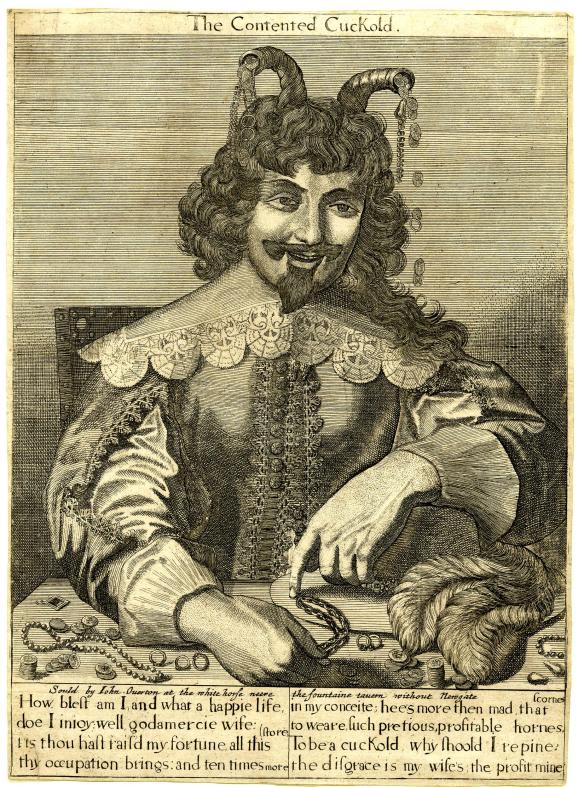

What should historians do with humour? How do we make sense of the roles it played in past societies? I wrestle with these questions when working on prints like The Contented Cuckold (1673) [Figure. 1].[3] Made by an anonymous engraver and published by John Overton, the print shows a cuckold smiling at his circumstances. This seems odd. Cuckolds – men whose wives had shamed them by committing adultery – were mocked and pitied in early modern culture, laughingstocks unmanned by women.[4] As Susan Foyster noted, ‘Cuckold’ was “the worst insult which could be directed towards a man”.[5] In the ballad ‘The Cuckold’s Complaint’ a man complains that his wife beats him if he even ‘touches her toe’ in bed. In other ballads the cuckold is beaten, scolded, or made to perform humiliating tasks for his dominant wife, tasks which captured the social death their shame had brought – “my dearest friends doe scoffe me” laments the cuckold in ‘Household Talk’.[6]

So why is The Contented Cuckold so pleased with himself? His fine clothes and the jewellery that clutters his desk tell us that he is rich, and coins falling from his cuckold’s horns show those riches to be newfound and reveal his wife’s infidelity to be their source. The verses explain:

How blest am I and what a happie life,

Do I inioy well godamercie wife:

Tis thou hast raised my fortune all this store

Thy occupation brings and ten times more.In my conceite, he’s more than mad that score

To weare such pretious, profitable hornes,

To be a cuckold why should I repine:

The disgrace is my wifes the profit mine.

The humour here rests on subverting expectations. Our cuckold’s life has been enriched by his wife’s infidelity, not, as society dictated, destroyed by it. But there is darkness here, too. How has his wife made him rich? Because he is no longer supporting her or – as the term “occupation” suggests – because he has become her pimp? The latter inverts the status of the cuckold. He is not emasculated, but in control, not foolish, but shrewd. The cuckold stereotype was one half of a twin fear in early modern England, the weak man, and the dominant woman. The two appeared together in ballads and cheap print as emblems of the world turned upside down. The Contented Cuckold disrupted that stereotype. He is both a cuckold, and a master who counts his winnings.

Who were prints like The Contented Cuckold made for? And what do they tell us about early modern England? My AHRC-funded project ‘British Printed Images to 1700: Integrating Visual Sources into Historical Practice’ considers these questions. It focuses on the thousands of single-sheet prints, titlepages, and book illustrations published in Britain before 1700. Many of these images are under-researched. How might we integrate them into the history of the period? How do they complement and challenge that history? What do visual sources tell us that other sources may not?

Excellent work has been done in the previous decades to help answer those questions. The political print, for example, is now regularly used by historians. Invaluable studies have detailed their roles in the construction and contesting of authority in the seventeenth century, placing prints alongside other media, oral and textual, as aspects of a public sphere of politics. Tim Harris’s and Mark Knights’s work on Restoration politics has located prints in a partisan news culture.[7] Alexandra Walsham showed how anti-Catholic political prints were used to oppose James VI/I and Charles I, Alastair Bellany placed political prints within a libel culture against Charles and Buckingham, and in a broad study of 1600-40 Helen Pierce showed how closely prints were involved in political debates across the early-Stuart period.[8]

There have also been impressive studies of the role of political prints in advocating Stuart dynastic ambitions, in the Sacheverell affair, and in cultivating loyalty to the Hanoverian monarchy.[9] In these studies, historians use political prints not as generic indices of popular attitudes but as makers of political opinion. That political prints have become an accepted part of how historians study authority was shown most powerfully by Kevin Sharpe’s trilogy of books on politics in Tudor and Stuart Britain. Here prints were woven into the study of authority alongside more traditional sources – political treatises, state papers, pamphlets – as part of political culture.[10]

But political prints are the exception. There are no equivalent studies on images as a way into the social, cultural, and intellectual histories of the period before 1700.[11] Important surveys by Anthony Griffiths and Malcolm Jones have shown the scope and variety of printmaking in our period, exposing the sheer range of topics that prints touched on, from travel, devotion, the natural world, maps, architecture, space and place, the history of the book, the reception of classical culture, military history, the history of science, and of the senses and the emotions, to name only a few.[12] Visual sources touch on how early modern people understood their world. They show us how early modern people represented race, understood the natural world, and visualised mores, ideas, and attitudes. Prints also reveal much about early modern attitudes to gender, demonstrating how masculinity and femininity were fashioned (in portraiture) and subverted and stereotyped (in satires).

This brings us back to The Contented Cuckold, a print which played with the ambivalences and ambiguities of gender, showing an unmanned man using wit to reassert his masculinity [Fig. 1]. The print has several stories to tell.

The first is about how British this ‘British’ print was. The Contented Cuckold was adapted from a French print, Le Cornard Contant (1640), published by Ciartres François Langlois a generation earlier [Figure. 2]. From the origins of this print and other ‘British’ prints like it – a significant percentage of which were based on German, Dutch, and other continental originals – we can learn much about the marketplace of the printing press.[13] Should we see that marketplace as European rather national? Are we, perhaps, seeing elements of a culture common across the West of Europe? And how did representations of gender, race, monarchs, or ideas change when they were copied or adapted and republished in a new context? There was often a significant gap in time – sometimes spanning multiple generations – between an original print and an adaptation. To what extent was meaning inscribed in a prints iconography or shaped by the context in which it was published?

The second story The Contented Cuckold tells is about masculinity. Historians understand the relationship between cuckoldry and laughter to be hostile and have shown how cuckolds were publicly derided to reinforce the patriarchal values deemed to be necessary to maintain order. The husband was master of the household, which was the building block of society and the state. Men not strong enough for mastery – and women who mastered them – were consequently shamed as threats to society. This was the purpose of ritual humiliations like skimmington rides, in which cuckolds (either in person or in effigy) were ridden backwards on an ass through their community to the jeers of crowds and the din of pots and pans; and of the display of cuckolds’ horns in libels posted around communities to publicise transgressions. The cuckold was laughed at, scorned and belittled. The Contented Cuckold subverts those expectations, asking us to laugh with the cuckold. How are we to understand what the role of humour is in this print?

Modern interpretations of laughter incongruity, relief, and superiority.[14] Incongruity theories see laughter as joyful. They argue that we laugh when something surprises us or inverts our expectations by deviating from the norm, as in puns and wordplay, slapstick, or anything out of keeping with conventional behaviour, or decorum. Relief theories (developed from Sigmund Freud) argue that laughter’s purpose is to release pent up anxiety, as in nervous laughter, or ease tensions to allow communities to function. An example would be the exorcizing of hostilities towards elites, the law, and the church in the ritualised mockery, license, and misrule of early modern carnivals. Finally, superiority theories assert that laughter is first and foremost a malicious phenomenon provoked by our observing something – a person, event, behaviour, or idea – we deem base, ridiculous, or inferior in some way. Laughter announces our feeling superior and belittles that which is laughed at.[15] Thomas Hobbes’ discussion of laughter in the Leviathan (1651) understood humour in this way, and the superiority theory has been prevalent in historians’ reading of laughter in early modern England.[16] We find it in polemic, in satires, and in shame punishments meted out by courts.[17]

But laughter’s role in early modern society was far broader than superiority. Recent studies have shown that humour was an important part of sociability. Kate Loveman, for example, has noted that jesting and pranking were crucial to forging fraternal bonds in elite clubs and societies.[18] Other studies have stressed that the emotions expressed in laughter – anger and contempt – were as concerned with relieving tensions and salving anxieties as they were with marking superiority.[19]

The Contented Cuckold’s dark humour touches on these themes of relief and sociability. Homosociability may be a significant context for the joke here, I think. The laughter in this print was not superior – we are not meant to mock this cuckold – but incongruous, surprising viewers with an oddity, an unmanned man content, even happy, with his fate. For men concerned about the precarity of their honour and reputation, and fearful of women’s ability to damage both, perhaps the print’s incongruous depiction of a happy cuckold appealed because it was relieving, provoking a misogynistic laughter at a man’s exercising of control over his errant wife. Was it safer, even comforting, to laugh with this cuckold when in the company of other men?

Maybe, maybe not. Either way, I’m still unsettled by the joke.

[1] For this aspect of laughter, see Robert Darnton, ‘Workers’ Revolt: The Great Cat Massacre of the Rue Saint-Sevérin’ in his The Great Cat Massacre and other episodes in French Cultural History (New York, 1984), 75-107.

[2] For an excellent treatment of this material see Simon Dickie, Cruelty and Laughter: Forgotten Comic literature of the unsentimental eighteenth century (Chicago, 2011).

[3] On this print and other images of cuckolds see Malcolm Jones, The Print In Early Modern England (New Haven, 2010), pp. 340-51.

[4] Susan Foyster, Manhood in Early Modern England: Honour, Sex and Marriage (London & New York, 1999), 67-73, 86-7, 104-17, 125-39, 161-76; Martin Ingram, ‘Ridings, Rough Music, and the “reform of popular culture” in early modern England’, Past & Present, 105 (1984): 79-113.

[5] Fosyter, Manhood, p. 7.

[6] ‘The Cuckold’s Complaint’ (1689-91) and ‘Household Talk’ (1603-25) in W. Chappell, ed., The Roxburghe Ballads, vols 1-3 (London, 1871-80), vol. III, p. 431 and vol. I, pp. 441-6.

[7] Tim Harris, London Crowds in the reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration until the Exclusion Crisis (Cambridge, 1987); Mark Knights, ‘Possessing the Visual: The Materiality of Visual Print Culture in late Stuart Britain’, in Material Readings of Early Modern Culture: texts and social practices, 1580-1730, ed James Daybell and Peter Hinds (Houndmills), 185-122.

[8] Alexandra Walsham ‘Impolitic Pictures: providence, history, and iconography in Protestant nationhood in early Stuart England’, Studies in Church History, 33 (1997): 307-28. Alastair Bellany, ‘Buckingham Engraved: Politics, Print Images and the Royal Favourite in the 1620s’ in Printed Images in Early Modern Britain: essays in interpretation (Farnham, 2010), 215-35. Helen Pierce, Unseemly Pictures: Graphic Satire and Politics in early modern England (New Haven, 2008).

[9] See Catriona Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity (London: Routledge, 2017); Stephanie Koscack, Monarchy, Print Culture and Reverence in Early Modern England: picturing royal subjects (London, 2020); Brian Cowan, ed., The State Trial of Doctor Henry Sacheverell (Maldon, MA & Oxford, 2012), 153-61, 187-89; Eirwen E.C Nicholson, ‘Sacheverell’s Harlots: Non-Resistance on Paper and in Practice’, Parliamentary History, 31:1 (2012): 69-79.

[10] Kevin Sharpe, Selling the Tudor Monarchy: authority and image in sixteenth century England (New Haven, 2009); Image Wars: promoting kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603-1660 (New Haven, 2010); Rebranding Rule: images of Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714 (New Haven, 2013). It should also be noted that there is a good body of historiography which has used images to study the religious history of the period. See Tara Hamling, Decorating the Godly Household: Religious Art in post-Reformation Britain (New Haven, 2010); Margaret Aston, Broken Idols of the English Reformation (Cambridge, 2016); Tessa Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge, 1991); David Davis, Seeing Faith, Printing Pictures: religious identity during the English Reformation (Leiden, 2013).

[11] There is, however, an excellent body of scholarship on material culture. See David R. M. Gaimster, Tara Hamling, & Catherine Richardson, The Routledge Handbook of Material Culture in early modern Europe (London & New York, 2017); Tara Haling and Catherine Richardson, Everyday Objects: Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture and its Meanings (Farnham, 2010).

[12] Antony Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain:1603-1689 (London, 1998); Jones, Print In Early Modern England.

[13] Jones, Print in Early Modern England, Appendix II & Appendix III.

[14] See Mark Knights and Adam Morton, ‘Introduction’ in idem, The Power of Laughter and Satire in Early Modern England: political and religious culture 1500-1820 (Martlesham, 2017), 2-10.

[15] For a consideration of how these theories translate to the early modern period, see Lucy Rayfield, ‘Rewriting Laughter in Early Modern Humour’ in Daniel Derrin and Hannah Burrows, eds., The Palgrave History of Humour, History, and Methodology (London, 2021), 71-91.

[16] Quentin Skinner, ‘Hobbes and the Classical Theory of Laughter’, in Leviathan After 350 Years, ed. Tom Sorrel and Luc Foisneau (Oxford, 2004), 139-66.

[17] See Patrick Collinson, ‘Ecclesiastical Vitriol: religious satire in the 1590s and the invention of puritanism’, in The reign of Elizabeth I: court and culture in the last decade, ed. John Guy (Cambridge, 1995), pp. 150-69; Adam Morton, ‘Laughter as a Polemical Act in seventeenth century England’ in Knights and Morton, Power of Laughter, 107-32.

[18] Kate Loveman, Reading Fictions, 1660-1740: Deception in English Literary and Political Culture (Aldershot, 2008); See Tim Somers, ‘Jesting Culture and Religious Politics in Seventeenth Century England’, Historical Research, 95 (2022): 19-44. Chapters by Cathy Shrank, ‘Mocking or Mirthful? Laughter in Early Modern Dialogue’, in Knights and Morton, Power of Laughter, 48-66.

[19] Foyster, Masculinity, 113-4. On relief and laughter in another context see Adam Morton, ‘Laughing at Hypocrisy: The Turncoats (1711), visual culture, and dissent in early-eighteenth century England’, Studies in Church History, 60 (2024): 312-339.

Pingback: A new life for ‘British Printed Images to 1700’ | the many-headed monster

Very interesting! Early modern needlework pattern books also reprinted images from other countries, as well as reflecting similar social anxieties about social mobility, women’s roles, and luxury. From my research, I agree with your argument about considering them in a European context rather than national. In particular, I dug into John Taylor’s The Needles Excellency for my master’s thesis. Thanks for your post.