[In our series ‘A Page in the Life’, each post briefly introduces a new writer and a single page from their manuscript. In this post, Emily Vine examines the daily records of a remarkably busy woman in late eighteenth-century London.]

From 1773 to 1830, Anna Margaretta Larpent, the wife of John Larpent, Examiner of Plays, kept a diary of her daily life divided between Newman Street, London and Ashtead in Surrey. She recorded the time she woke up and went to bed each day, the meals she ate, the details of the books she read, the letters she wrote, her daily prayers, her time spent sewing and shopping, her family business, and her significant contribution to her husband’s work in theatre licensing. The delight is in the detail; even in predictable repetitions such as ‘Rose at 8. Breakfasted. Prayed’, Larpent is brought to life on every page.

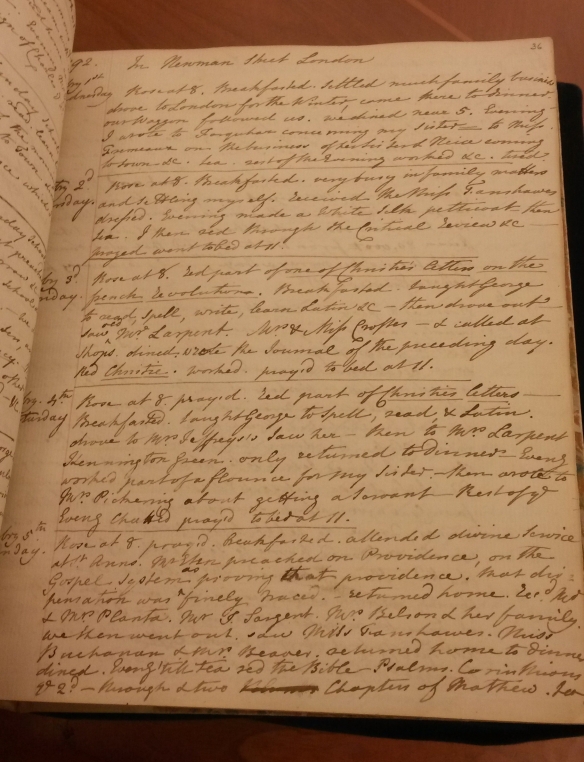

In the first week of February 1792, she recorded the following:

Huntington Library, HM 31201, Vol. 1, p. 36.

1792 In Newman Street London

February 1st Wednesday Rose at 8. Breakfasted. Settled much family business above to London for the Winter, came there to dinner. Our Waggon followed us. We dined near 5. Evening I wrote to Farquhar concerning my sister … to miss Garmeaux on the business of her his Lord Neice coming to town &c. Tea rest of the Evning worked &c. Tired.

February 2nd Thursday Rose at 8. Breakfasted. Very busy in family matters and teaching myself. Received the Miss Fanshawes dressed. Evening made a White Silk petticoat then tea. I then red through the Critical Review &c. prayed went to bed after.

February 3rd Friday Rose at 8. Red part of one of Christie’s Letters on the French Revolution. Breakfasted. Taught George to read, spell, write, learn Latin &c. then drove out saw old Mrs Larpent. Mrs & Mis. Crofter. I called at Shops. Dined. Wrote the Journal of the preceding day. Red Christie. Worked. Prayed to bed at 11.

February 4th Saturday Rose at 8. Prayed. Red part of Christie’s letters. Breakfasted. Taught George to spell, read & Latin. Drove to mrs Jeffrey’s saw her then to Mrs Larpent Kennington Green. Only returned to dinner. Eveng worked part of a flounce for my sister. Then wrote to Mrs Pickering about getting a Servant. Rest of ye Eveng Chatted prayed to bed at 11.

February 5th Sunday Rose at 8. Prayed. Breakfasted. Attended divine service at St Anns. Mr Eten preached on Providence, on the Gospel System as proving that providence. That dispensation was finely traced – returned home. Recd. Mr and Mrs Planta, Mr S. Sargent. Mrs Belson & her family. We then went out. Saw Miss Fanshawe, Miss Buchanan and Mrs Beaver. Returned home to dinner. Dined. Eveng till tea red the Bible. Psalms. Corinthians. & 2d – through & two Chapters of Matthew. Then copied the journal of a fortnight past in this book. Prayers. To bed at 11.

On this page we see a snapshot of Larpent’s life over a single week, focused on the life of her family, rather than a record of London news or events of national importance. While Larpent moved in important circles, worked as a theatre censor and had an eventful social life, it is the minutiae of her daily routine, the details of her time at home and her solitary reading which she devotes the most space to.

As she records her daily goings-on within the diary, so too does diary-writing shape her routine. She sets aside time to write an entry every day. She frequently breaks the fourth wall of the diary, reflecting upon her method of writing the very journal the reader is holding, noting time spent copying out past entries from a different book.

What is most striking is Larpent’s education. She reads French, Italian, and Latin and appears to spend a couple of mornings each week teaching these languages to her son George. She uses the journal to log details of the books she reads and her responses to them, immersing herself in volumes as diverse as a recent history of the French Revolution and The Critical Review. She structures prayer into her daily life; praying first thing in the morning or before she goes to bed, reading the bible, (Corinthians, Psalms, Matthew) and when, on the Sunday, she hears a sermon a short walk away from Newman Street in St Anne’s Soho, she critically engages with the content of it.

As well as dividing her time between her London and Surrey homes, Larpent records visiting friends across London and its environs, travelling four miles down to Kennington Green and frequently receiving visitors in her own home. While some scholars have suggested that Larpent had been stifled by her husband, this page gives the impression of an independent woman immersed in London society, a woman who combines the traditional roles of running the household with her involvement in the male-dominated theatre business, a woman of learning and agency.

Yet it is also the diary itself that helps fashion Larpent as a woman of learning and agency. The journal is a tool that permits her to reflect upon the books, sermons, and people she encounters; it both documents and facilitates her introspection, her desire to record and self-edit. While the process of writing fulfilled Larpent’s desire for self-improvement, so too has the end product solidified her place within the historical record.

Sir Martin Archer Shee portrait of Anna Margaretta Larpent (date unknown)

Source: Huntington Library, HM 31201, Vol. 1, p. 36.

Pingback: A Page in the Life | the many-headed monster

Your page in the life posts are utterly fascinating. To see into the daily lives or ordinary – and not so ordinary – people, the details of which might otherwise be unknown is so interesting. They just reveal so much. A great series

Thanks for this fascinating contribution Emily. One of the things that has struck me about all of the posts so far is that these forms of life writing not only serve as evidence of literacy skills, they also detail a whole host of other everyday skills and competencies – be that numeracy in Jacob Bee’s financial accounts, language skills and clothes-making here with Larpent, and the ability to tell time and date events that crops up here and there. They all provide a fascinating insight into the everyday skills that people deployed in negotiating their daily lives. Anyway, not really a question, but an interesting emerging theme in this series, and something it will be interesting to think about in relation to variables of gender, occupational, geography, chronology etc as it develops.

Wonderful source, Emily! She certainly does write a lot about writing, doesn’t she? As you say, she writes about her diary writing but also about writing letters (e.g. ‘I wrote to Farquhar concerning my sister’). Do you think this is because she is just recording all her tasks throughout the day (i.e. she sees writing letters as an important part of her social/economic role)? Or perhaps as a sort of practical calendar of her correspondence? My Joseph Bufton has a list of all the letters he sends and receives from his brother in Ireland in the 1680s.

Pingback: Anna Larpent, 18th Century Diarist and Lover of Plays | Every Woman Dreams…