The second post in our Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover comes from Scott Eaton, an ECR interested in early modern witchcraft, religion, art and print cultures. His book on the witch-finder John Stearne is available from Routledge now. You can follow him on twitter: @StjEaton.

On 22 August 1651 Christopher Love was executed for treason for conspiring with Royalists to restore the King, Charles II, to the throne. His wife, Mary Love, had worked tirelessly to try and save him. While he was being held in the Tower of London, Love petitioned, ‘stood dailie’ at Parliament’s doors and even sent messages to Cromwell in Scotland (at the cost of £100!) in the hope she might secure her husband’s release. Unfortunately, she failed in her efforts. Shortly after Christopher’s death, however, Mary published her petitions and included letters they had written to each other before he was executed. Her publications can provide insight into petitioning, print and gender roles in seventeenth-century England.

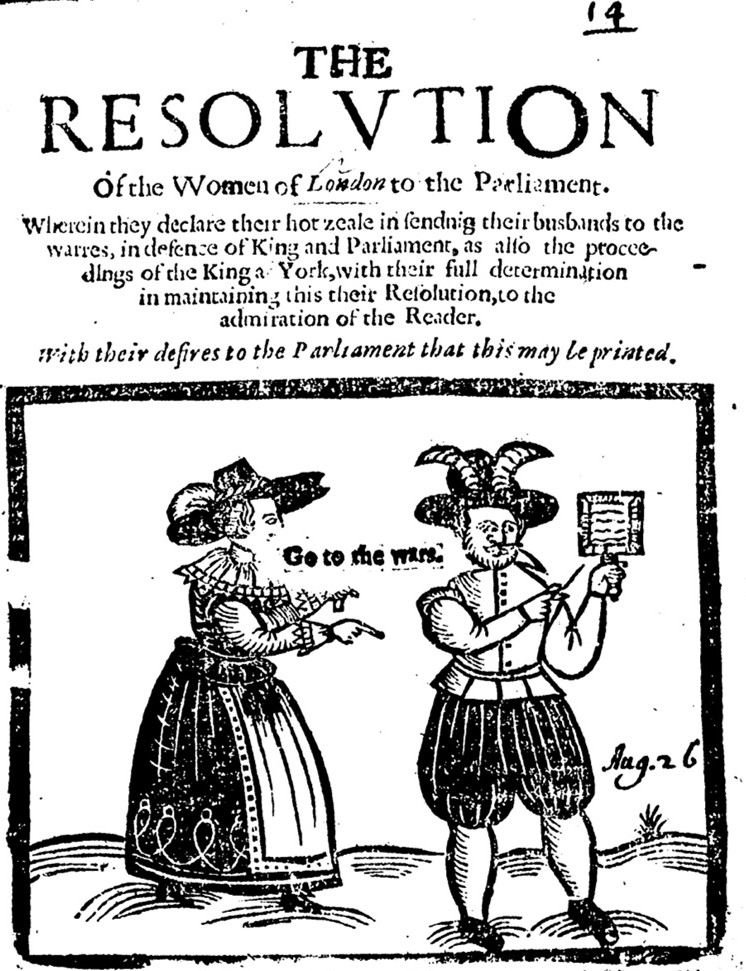

Petitioning was an acceptable way for the ‘ruled’ to address the authorities and make their voices heard, whether seeking action, intercession or mercy, like Love. The 1640s saw a breakdown over censorship of the press and a rise of female assertiveness in the political arena, allowing printed petitions attributed to women to proliferation more widely than before. Mary Love’s printed petitions obviously came after these events had happened, giving her a precedent to follow.

Mary Love (fl.1639–d.1663) was the wife of Christopher Love (1618–1651), the Presbyterian minister of Lawrence Jewry in London. Aside from that, little is actually known of Love’s life. Her father, Matthew Stone, was a London merchant, who, along with her mother, died when Love was young. She then became ward to John Warner (Mayor of London), where she met her husband who was employed as Warner’s chaplain in 1639. In 1642, Christopher left to serve as a Parliamentary chaplain, and on his return in 1645 he married Mary. They had five children but only two survived, their last child dying six months after Christopher’s execution. Mary Love truly appears on the historical radar once her husband is accused of treason, which spurred her into action.

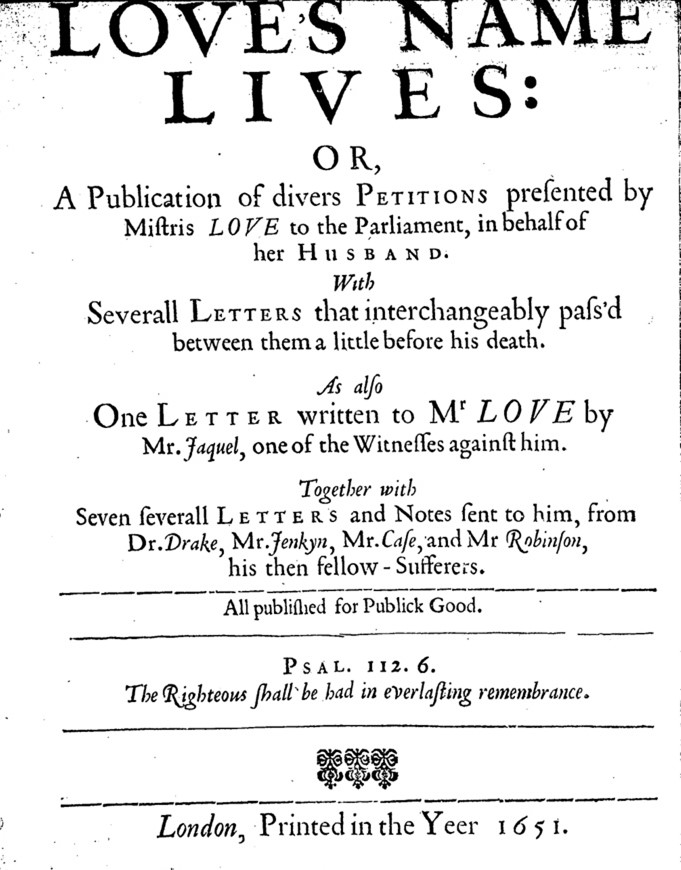

In her publications, Love’s works follow tropes that were common in women’s petitions of the 1600s. In Love’s Letters and Love’s Name Lives, Mary deploys language which is based on contemporary gender stereotypes. She refers to herself as a mother, a wife, a ‘poor hand-maid’, and a soon-to-be ‘unhappy widow’. She begged the godly men of Parliament to take pity on her children who were distraught at the prospect of Christopher’s death. Love even uses metaphors based around the womb and breasts, and suggests to Parliament that the release of her husband would bring great joy to her unborn child and ‘all the tender-hearted Mothers in England’ and would glorify God.

Alison Thorne noted that female petitioners were not ‘averse to milking gender stereotypes for their own ends; they tended to harp on women’s “fraile condition” as “the weaker vessel”, declaring that they “cannot but tremble at the very thoughts of the horrid and hideous facts which modesty forbids us to name”’. Thorne uses Elizabeth Lilburne’s petition of 1646 as an example, which mirrors Love: Lilburne appealed to the House of Commons on behalf of husband John, protesting, ‘her husband and children … be very nigh ruine and destruction, unlesse your speedy and long-expected justice, prevent the same. Which your Petitioner doth earnestly intreat at your hands, as her right, and that which in equity, honour, & conscience, cannot be denied her’. Using feminine language was clearly an attempt to elicit sympathy from its readership. The public could have found displays of feminine vulnerability more moving, maximising the pathos of their situation. Although Love’s use of gendered language was conventional, it was also strategic, showing some rhetoric and political astuteness.

From 1651, Mary Love started crafting a biography of Christopher, resulting in three printed works and two manuscript versions which detailed his life. Love ultimately failed to save her husband, but petitioning did give her some success. After realising an acquittal was unlikely, she implored Parliament to banish Christopher (a minister) to New England where he could proselytize to its natives, resulting in his execution being delayed by a month. According to Mary’s printed letters, by this point Christopher had resigned himself to the fact he was going to die, and made peace with the fact. He was even joyous that their marriage was being annulled at his death, knowing that they would eventually be reunited and be married to Christ the ‘bride-groom’.

Mary’s main success was saving her husband’s reputation, portraying him as a godly man, not a criminal. Love cast her husband as a prophet who had been murdered for condemning the regicide and, in the manuscripts, accused Parliament of manipulating the law and warned that his murderers would answer to divine vengeance. The printed works exclude the latter, as Love’s primary aim was to defend her husband’s name in print. However, Mary was able to garner plenty of support in her campaign because of her husband’s position. As an executed Presbyterian minister, he became central to the propaganda circulated by London Presbyterians who, with Mary, styled him as a martyred saint. Mary Love was an important contributor to their propaganda, providing much fuel. Whether Mary’s writing intended to reflect her stance as a mother and wife to Christopher seeking justice, or as a political activist furthering the Presbyterian cause is unknown. Nonetheless, she succeeded in both endeavours with her letters being reprinted well into the 1700s. Mary Love’s printed works show how gendered language could effectively be deployed in petitions and how the powerless had means to elicit popular opinion to turn the tables on their rulers, challenging authority and our concepts of early modern society.

Further Reading

Love, Mary, ‘Life of Mr Christopher Love’, Dr William’s Library, MS 28.58.

———, Love’s Letters, His and Hers, to each Other (London, 1651).

———, Love’s Name Lives (London, 1651).

Rhodes, Emily, ‘Crime and women’s petitions to the post-Restoration Stuart monarchs’, The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England (2021), available here.

Thorne, Alison, ‘Narratives of female suffering in petitionary literature of the Civil War period and its aftermath’, Literature Compass, 10:2 (2013), pp. 134-145.

Weil, Rachel, ‘Love [néeStone], Mary (fl.1639–1660)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Bibliography (2010), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/74442.

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster