We are delighted to launch our Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover with this post from Imogen Knox. Imogen is an M4C funded doctoral researcher at the University of Warwick whose work focuses on suicide, self-harm and the supernatural in Britain, 1560-1735. Find her on twitter at @Imogen_Knox.

CONTENT WARNING: this post contains discussion of suicide.

Self-destruction was interwoven with the roles of both witch and bewitched in early modern Britain. Witches committed spiritual suicide in signing themselves over to the devil, and in turn the devil tempted his imprisoned servants to self-destruction to secure his grip on their souls. The spiritual and actual suicide of witches, like criminals, reinforced their guilt in the contemporary imagination. Witches also tormented their victims with temptation to self-destruction.

Both those afflicted by witchcraft and witches themselves expressed self-destructive temptations. One such admission would produce sympathy, the other scorn. In this post I examine the case of the witchcraft of Anne Bodenham and her victim Anne Styles to show how, by mirroring each other’s self-destructive behaviours, the women negotiated contemporary ideas around innocence, guilt, female nature, and spirituality. One would emerge as an innocent victim, the other an unrepentant sinner.

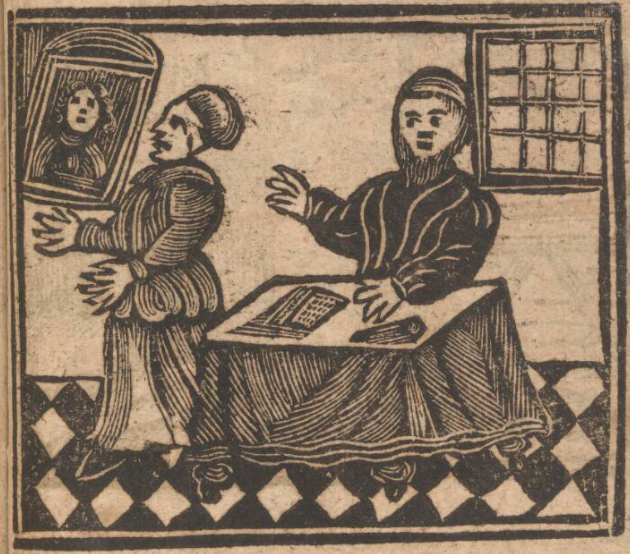

Anne Bodenham, of Fisherton Anger, near Salisbury, was a reputed cunning woman. It was her ability to locate stolen goods that first brought Anne Styles to her in 1653. Styles, a young woman employed as a maid in the Goddard household, was illiterate and ‘altogether ignorant of the Fundamentall grounds of Religion’ according to the court clerk Edmund Bower. In contrast, the eighty-year-old Bodenham owned ‘a great many notable books’ and claimed to have been taught by the infamous Dr Lambe. Styles made multiple visits to Bodenham, to consult on various issues for the Goddard family, chief among the fear of Styles’ mistress that she was to be poisoned. After several visits, Bodenham offered to take Styles on, ‘to live with her’ and ‘teach her to doe as she did’. However, when Bodenham transformed herself into a cat, Styles was ‘very much affrighted’. Bodenham, seeing that she had misjudged the situation, let Styles go. To ensure that Styles would not ‘discover her’, Bodenham had Styles sign her name in blood in a book, while two conjured spirits looked on.

Unfortunately for Styles, not only had she just unwittingly signed herself over to the devil, but she was also embroiled in a poisoning plot against her mistress. The purchase of arsenic from the local apothecary, apparently for use in a countercharm, was traced back to her and she became the chief suspect. Styles fled, but was caught. Upon her apprehension, to exonerate herself of the poisoning charge, she ‘did confess and acknowledge all the transactions and passages between the Witch and her’. Styles then fell into fits, crying out ‘that base and plaguy Witch Mistress Boddenham hath bewitched me’.

Whether Styles knew it or not, she was employing tropes of bewitchment in crying out against spectral tormentors, demonstrating supernatural strength, and exhibiting suicidal tendencies, attempting to throw herself into the fire and tearing at her own skin. She was nevertheless committed to prison for attempted poisoning, where she joined Bodenham, who was also languishing in jail.

Styles’ fits continued throughout her three week stay in prison, during which she was held down to prevent her from tearing at herself. During this period, Styles managed to position herself as the penitential victim of Bodenham and the devil’s trickery. Negotiating cultural expectations of her sex, age, and social position, Styles lamented her ‘wretched’ nature and hinted at the suicidal temptation she was subjected to by the devil:

‘I see him also now standing on the top of the house… he strives to get me from the people, and I think I were as good goe with him, for then I shall be at better ease and quiet’.

In her newfound religious awareness, Styles exhibited her despair that she had caused her ‘own damnation’ and ‘cut [her]self off from Heaven’. There was ‘no hope’ now that the devil had ‘entered within [her]’. Edmund Bower, who spoke with both women during their imprisonment, reassured Styles that ‘salvation is to be had for the worst of sinners’.

Bodenham, when asked the same questions about the state of her soul, appeared more assured of her salvation, and her ability to affect this herself. Bower was not impressed with Bodenham’s lack of repentance, while the torments and grovelling of Styles were ‘so sad a spectacle’ that they could only evoke pity. Bodenham was cast as guilty, and Styles, despite having signed herself over to the devil, manipulated the complex interplay of innocence and guilt to emerge as the innocent party, displacing her guilt and sin onto Bodenham.

Bodenham, sharing the prison with her victim, picked up on Styles’ ability to garner sympathy. In the maid’s presence, Bodenham railed against her, and screamed that the devil would tear her, imitating Styles’ description of her suffering. Bodenham’s cries that she would be ‘torn in pieces, and the devil would fetch [her] away’ had little impact. While Styles repeatedly termed Bodenham a ‘wicked base woman’, Bodenham was reproached for calling Styles a ‘whore’.

Styles articulated herself as moving from ignorant young woman, to religiously awakened victim of despair, to receptacle of God’s grace, a narrative which was lapped up by onlookers. Bodenham only increased her appearance of guilt by attempting to mimic Styles’ actions. While Styles had been consoled and cosseted upon her admission of suicidal temptation, Bodenham’s suicidal outburst was reprimanded. Being informed that she was to be executed, Bodenham ‘fell into a rage, and wished for a knife, she said she would run into her heart-blood’. The reproachful response to her desperation was, ‘Oh Mistress Bodenham, you would not offer to do such wickedness, would you?’ and she was led away to the gallows.

Whether either woman was genuinely suicidal at any point during the narrative is besides the point, though their imprisonment, the looming threat of trial, and particularly for Bodenham, the possibility of execution, would certainly have been enough to provoke despair. This narrative exposes the ways in which the same behaviours would be met with different reactions, due to the predetermined roles in which each woman had been cast, something influenced by the cultural expectations around their gender and respective ages. The elder Anne, despite mirroring the self-destructive behaviour of the younger Anne, only reinforced her guilt, while the younger provoked sympathy through her sufferings. Admissions of temptation to suicide could create sympathy for some, but not others.

All quotes taken from Edmund Bower, Doctor Lamb revived, or, VVitchcraft condemn’d in Anne Bodenham (London, 1653), accessible through Early English Books Online (£).

Another, more sensationalist and simplified narrative of the case exists in Anon, Doctor Lambs Darling: or, strange and terrible news from Salisbury (London, 1653), accessible through EEBO (£).

Further reading:

Malcolm Gaskill, ‘Witchcraft, Politics, and Memory in Seventeenth-Century England’, The Historical Journal 50:2 (2007), 289-308

Louise Jackson, ‘Witches, wives and mothers: witchcraft persecution and women’s confessions in seventeenth-century England’, Women’s History Review 4:1 (1995), 63-84

J. Lonnqvist and Kalle A. Achte, ‘Witchcraft, religion and suicides in the light of The Witch Hammer and contemporary cases’, Omega 5:2 (1974), 115-125

Jonathan Willis, ‘Mental Illness: An Early Modern Perspective’, The Many Headed Monster (2020)

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster