Our latest post in the Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover is from Joe Saunders. Joe has just started a PhD at the University of York using wills to study the social networks of the print trade in England c.1557-1666. Find Joe on twitter at @joe_saunders1.

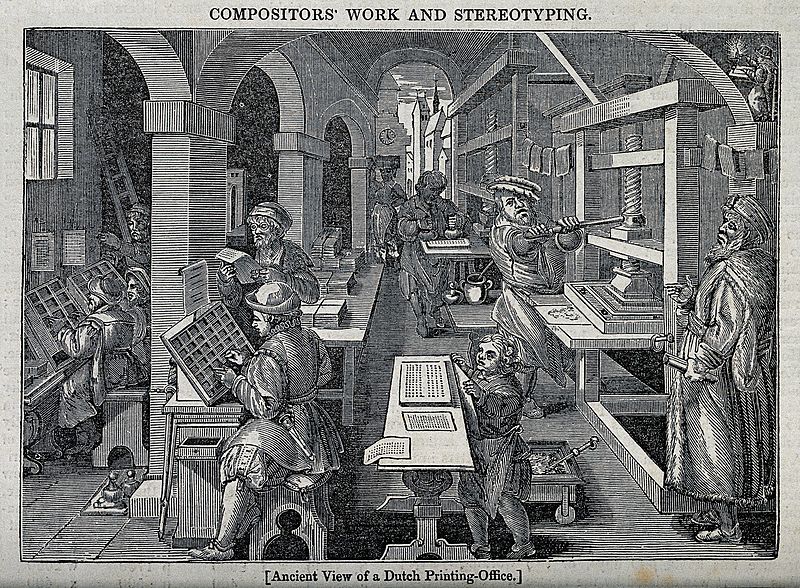

We are this year ‘working from home’; struggling with work-life balance; and have ‘Key Workers’ in our supermarkets, hospitals and care-homes. What constitutes important labour is a contemporary debate but also interests historians who seek to define and locate work. Histories of literature are a case-in-point, with focus oscillating between the labour of authors, readers and publishers. In recent decades we have come to know a great deal about text creation and circulation during the hand-press era with work on the producers and movers of texts; publishers, printers and booksellers as they turned an author’s ideas into something tangible and passed them to an audience. The transfer from the author’s mind to printed page and then to the reader required a significant amount of labour from a variety of actors in a myriad of roles from financing a text through to those who carried the finished products along country roads.

Bertolt Brecht in his 1935 poem ‘A Worker Reads History’ imagined how the workers who built the great monuments of the world figured into histories dominated by great men. He asked ‘but was it kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone?’. Of course, the answer is no, but their names adorn these structures nonetheless. Though the process of text creation and movement in early modern England was gendered, classed and regionalised research has necessarily focused on the better offs who left their names on imprints and records of the Company of Stationers; the livery company which held a theoretical control over the membership and products of the print trade. This is the case across the History of the Book where source survival means most work on reading and authorship is also done on the middling sorts and elites.

The 2020 publication Women’s Labour and the History of the Book in Early Modern England brought together a range of essays dealing with reading, authorship and production. The focus was more towards countesses than chapmen-or-women but an exception was Craig’s essay on the rag-women who collected material for papermakers. This research recovered the labour of people who were critical to the production of texts but are largely absent from the records and therefore from our understanding. It was argued implicitly that to look for the lowest sort of women in the trade is the first step to finding them.

This work is difficult given the scarcity of what the lowest sort of people left to the historical record but also because of our own notions of where we centre labour in the early modern text trade. Much labour was conducted outside what we consider as being trade work including people ostensibly belonging to other trades and people like financial brokers, warehousemen and transporters whose status was more uncertain. Journeymen and apprentices are a clear route for enquiry, but as Craig has shown there was also an array of people doing work that while contributing to the conduction of trade, wasn’t properly print trade work at all.

By studying the trade outside of trade records, using other historical sources we can gain an alternative perspective. Wills of printers and booksellers are valuable as they named their friends and family but also their servants. In the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, the highest court in southern England are 59 wills of members of the London trade between 1624-41. Fourteen testators left a bequest to someone they called their servant, maid or maidservant as well as several bequests to apprentices. Apprentices were often called servants but most of these bequests were to servants recruited on a more temporary basis who were paid for their labour rather than paying to learn a craft. Although the lowest sort, like these servants, appear only in small incidences it is in this fragmentary way that they have to be recovered.

Maidservants were a key part of many households in early modern England and their presence in Stationers’ wills underlines their presence in and around print trade work. With each bequest they are given names and become real in our minds. The bookseller Robert Allot bequeathed to his maidservants Judith and Mary £5 each. Allott appeared on numerous imprints that year including Lewis Bayly’s The Practice of Piety. During his life he had been involved in the publishing or sale of works by Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare among many others. The work that Judith and Mary did, even if they never laid hands on a text, would have been domestic labour that enabled Allott to carry out his trade. Maidservants like them are named throughout wills. John Haviland the printer and publisher gave to his maidservant Ellinor Galley ‘the sume of twentie shillinges’. He had worked on many texts in the year before he died including by Sir John Suckling, Inigo Jones and Francis Bacon. The bookseller Anne Boler’s maidservant Winifred Ellis received from her 40s. The bookseller Edward Aggas bequeathed to his servant Anne Parry £5. John Grismond, the ballad publisher and typefounder gave his servant Joan Black 40s and another 40s to make her a mourning gown.

Stretching our concept even further we can also think about those working in and around book shops and printing houses but not belonging to them. The bookseller and many times Master of the Stationers’ Company Thomas Man gave to Isabel Garbidge ‘my late water bearer’ 40s while the bookseller Richard Ockould bequeathed to Robert Sanders ‘the water bearer’ 10s.

Books contain the names of their authors, printers and booksellers but early modern print culture was enabled by the work of the lower sort of people whose labour was not glamourous, well recorded or even ‘of’ the trade. Historians of early modern print must look hard and marshal our imaginations to conceptualise them into our analysis. Their names are just the start.

Wills from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury are at The National Archives. Referenced here: Edward Aggas. PROB 11/145/69 [21 January 1625]; Thomas Man. PROB 11/146/50 [16 June 1625]; Richard Ockould. PROB 11/166/522 [20 November 1634]; Robert Allott. PROB 11/169/271 [10 November 1635]; Anne Boler. PROB 11/176/126 [3 February 1638]; John Haviland. PROB 11/178/459 [20 November 1638]; John Grismond. PROB 11/178/749 [31 December 1638].

Further reading:

Heidi Craig, ‘English rag-women and early modern paper production’ Valerie Wayne (ed.), Women’s Labour and the History of the Book in Early Modern England. (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 29-46

Stephen Bernard, ‘Establishing a Publishing Dynasty: The Last Wills and Testaments of Jacob Tonson the Elder and Jacob Tonson the Younger’, The Library 17:2 (2016), 157-166

Helen Smith, ‘Grossly Material Things’: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012)

Adrian Johns, The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998)

James R. Farr, ‘On the Shop Floor: Guilds, Artisans, and the European Market Economy, 1350-1750’ Journal of Early Modern History 1:1 (1997), 24-54

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster