The next post in our Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover is by Eleanor Hedger. Ellie is an M4C doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham, and she has recently submitted her thesis, entitled ‘Soundscapes of Punishment in Early Modern England’, for examination. Find her on twitter @ellie_hedger.

It’s December 11, 1633. After hearing St. Sepulchre’s Church toll its ominous passing bell, you’ve made your way to Tyburn to witness the latest spectacle of public execution. This time, a woman found guilty of infanticide faces the scaffold. Hundreds of spectators have gathered in the surrounding streets and fields, with onlookers peering out of nearby windows or clambering onto rooftops. You jostle amongst the crowd in an attempt to catch a glimpse of the spectacle, but to no avail. As the victim makes her final speech you strain to hear her words, but her voice is drowned out by the noise of the crowd. Once the grisly spectacle has come to a close you make your way home, but the doleful sounds of a nearby ballad monger selling copies of a song about today’s execution catches your attention. Having seen or heard very little of her demise, you want to know more, so you hand over a penny to the ballad monger. You fold up your copy of the large, single-sheet song, slip it into your pocket and return home, ready to sing, read, and listen to it with friends and family later that day.

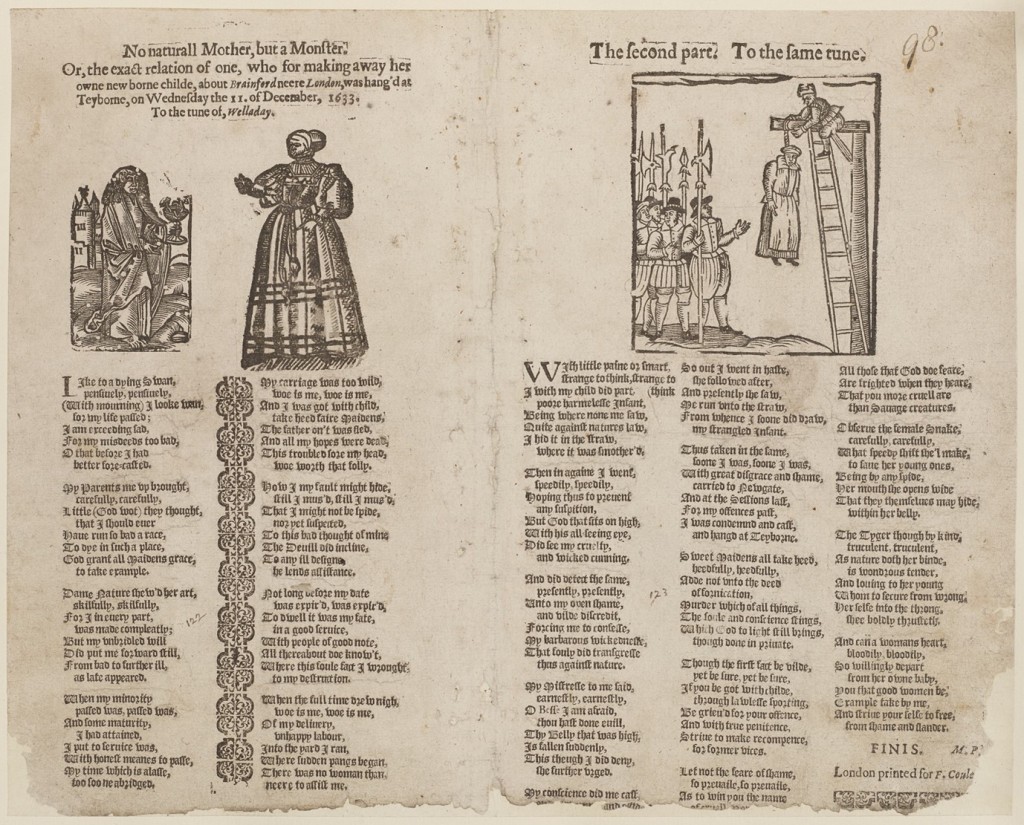

Execution ballads, such as the one illustrated above, were an extremely popular form of news media in early modern England. Taverns, marketplaces, homes, and even the execution space itself resounded with the singing of these macabre ditties, allowing the public to reflect upon and relive the brutal spectacle of execution through the medium of song. Whilst ballads were probably read out loud, they were, first and foremost, intended to be sung, and the majority of ballad sheets usually contain an inscription under the title indicating its tune. These popular and memorable melodies were used over and over again, garnering new thematic and emotional associations with each rendering. The reuse of familiar tunes for new texts—a technique known as ‘contrafactum’—raises important questions concerning the reception and experience of execution ballads: how did the cultural associations of a melody amplify or subvert the meaning of a ballad text? And to what extent did the melodies of these songs influence the perception of public executions in the popular imagination? In this post I explore some of these intriguing questions by tracing the evolution of a well-known ballad tune called ‘Welladay’.

‘Welladay’ is named as the tune for at least six extant execution ballads from the seventeenth century. Musically, it has many of the characteristics associated with popular and memorable ballad tunes: it consists of just four musical phrases, the first two of which mirror each other closely in melodic shape and rhythm, as do phrases three and four, aiding the memorisation process. If you listen to the tune, it might seem surprisingly jovial considering it was used for songs about death. Here’s why: ‘Welladay’ is written in the mixolydian mode, which is essentially a major scale with a flattened seventh, and in contemporary Western music we usually associate major keys with happiness and minor keys with sadness. Early modern people also believed that modes could stir up specific emotional responses, but these responses have changed over time. According to Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, the mixolydian mode ‘had an absolute dominion over Grief and Sadness’, and was ‘only fit for Tragedies, and to move Pity and Compassion’.[1] It is not surprising, therefore, that ‘Welladay’ was named as the tune for various execution ballads.

During the first few decades of the seventeenth century, ‘Welladay’ was named as the tune for a number of ballads recounting the executions of virtuous noblemen. The first of these is A lamentable Dittie composed upon the death of Robert Lord Deuereux, which offers a sympathetic account of the life and downfall of the Earl of Essex. The text fashions a posthumous depiction of Devereux as a brave, virtuous, and generous hero, emphasising his military accomplishments and loyalty to his country. Following Essex’s death in 1601, a ballad celebrating the accession of James I in 1603 also named ‘Welladay’ as its tune. Although the text celebrates James’ accession, it also mourns the passing of the ‘prudent’, ‘carefull’, and ‘kinde’ Queen Elizabeth: indeed, the theme of loss is heightened in the choice of melody, due to the tune’s previous association with the death of a beloved hero. In 1618, a ballad about the execution of Sir Walter Raleigh was also set to ‘Welladay’, and like the ballad about Devereux, the text evokes sympathy for Raleigh throughout. By this stage in its life then, ‘Welladay’ was infused with elements of virtue, nobility, and masculinity.

Let’s return to the ballad you hypothetically purchased upon witnessing a public execution at Tyburn. In contrast to the noble deaths of Devereux and Raleigh, this ballad, entitled No naturall Mother, but a Monster, narrates the downfall and execution of a deviant woman who murdered her child shortly after giving birth. The ballad text offers a detailed, first-person account of her reprehensible sins, describing her as ‘barbarbous’, ‘wicked’, and ‘cunning’; a woman that was ‘more cruell…than Savage creatures’. But as you start to sing your newly purchased ballad, which is also set to ‘Welladay’, the tune stirs up memories of songs about Sir Walter Raleigh, James I, and Robert Devereux. Whilst the text encourages you to revile this murderous woman, the tune evokes feelings of sympathy and compassion as you remember Raleigh and Devereux’s noble fate. On the other hand, the melody might help remind you of the protagonist’s act of gender subversion: by murdering her child she has departed from traditional values of femininity and motherhood, and this violent disruption to the patriarchal order is amplified through the virile associations of the ‘Welladay’ melody.

We can never truly know how early modern men and women received and understood these songs, but it is important to consider the potentially unstable and contradictory interpretations that ballad tunes could engender: whilst text and image could say one thing, melody could imply another. It is only when we consider ballads as musical, as well as textual, phenomena, that we can fully grasp the various possible messages that these songs conveyed.

Further reading:

Christopher Marsh, ”Fortune my Foe’: The Circulation of an English Super Tune’, in Dieuwke Van Der Poel, Louis P. Grijp, and Wim van Anrooij (eds.), Identity, Intertextuality, and Performance in Early Modern Song Culture (Leiden: Brill, 2016), pp. 308-330.

Una McIlvenna, ‘The Power of Music: The Significance of Contrafactum in Execution Ballads’, Past & Present, 229/1 (2015): pp. 47-89.

Una McIlvenna, ‘When the News was Sung: Ballads as News Media in Early Modern Europe’, Media History, 22/3-4 (2016): pp. 317-333.

Sarah Williams, Damnable Practises: Witches, Dangerous Women, and Music in Seventeenth-Century English Broadside Ballads (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).

[1] Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, The vanity of arts and sciences (London, 1676), pp. 56-7.

Looks like the “ballad monger” put considerable work preparing this, or were they generic and printed up for chaps like him to earn a few pennies?

Great post Eleanor. It was a good idea for the writers of the execution ballads to use the same familiar tune for their semi literate London audience of the 17th century. “Welladay” must be a spiffy or at least melodious and repetitive tune, thus easy for the crowd to remember. However, using the same tune for the execution ballad of the noble Essex and Raleigh and then for the unfeminine like woman who committed infanticide seems incongruous. But as you say, Eleanor, the manly tune of Welladay can emphasize the odd behavior of the child murderer. With no details about this woman, we can only wonder if the child’s death was unintentional due to the mother’s lack of midwifery skills and possibly giving birth alone. These executions ballads appear to be easy to obtain on your way home from the big event. And I see a comparison to social media today where a tweet or a post is instantaneous.

Cheers

Patricia

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster