The next post in our Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover is by Dr Robert W. Daniel of the University of Warwick. Robert is a Post-Doctorate Researcher and General Secretary of the International John Bunyan Society. Follow him at @BunyanSociety. In this post, he offers us insights into the petitions and diaries of women who lost their children as a direct result of religious persecution.

CONTENT WARNING: This post contains accounts of miscarriage and stillbirth.

Women who did not conform to the Established Church of seventeenth-century England – labelled ‘puritans’, ‘fanatics’, ‘nonconformists’, ‘plotters’, or ‘dissenters’, paid a heavy, if not the heaviest price, in their fight for religious equality. They resisted religious uniformity by courageously, often peacefully, contesting pecuniary laws prohibiting alternative forms of worship, unjust imprisonments and the distrainment of goods, and the law making weekly parish church services compulsory. In researching the history of this struggle, I was struck at how frequently these women, as mothers, suffered child loss as a direct result of State sponsored religious persecution. Through their diaries, petitions and pamphlets, women depicted the trauma of stillbirths, miscarriages and neo-natal deaths as one of the tragic consequences of their struggle for religious freedom during a period of intense religious intolerance.

In this blog post I want to examine some examples of maternal suffering that need to be re-incorporated into our reading of the history of English religious nonconformity. Doing so will reveal not only the horrific (and underexamined) effects of religious persecution during this period, but also the affective discourse and mediums in which a denominationally and politically diverse cross-section of women (Baptists, Presbyterians, Quakers and Levellers) sought to make these known to a broader audience.

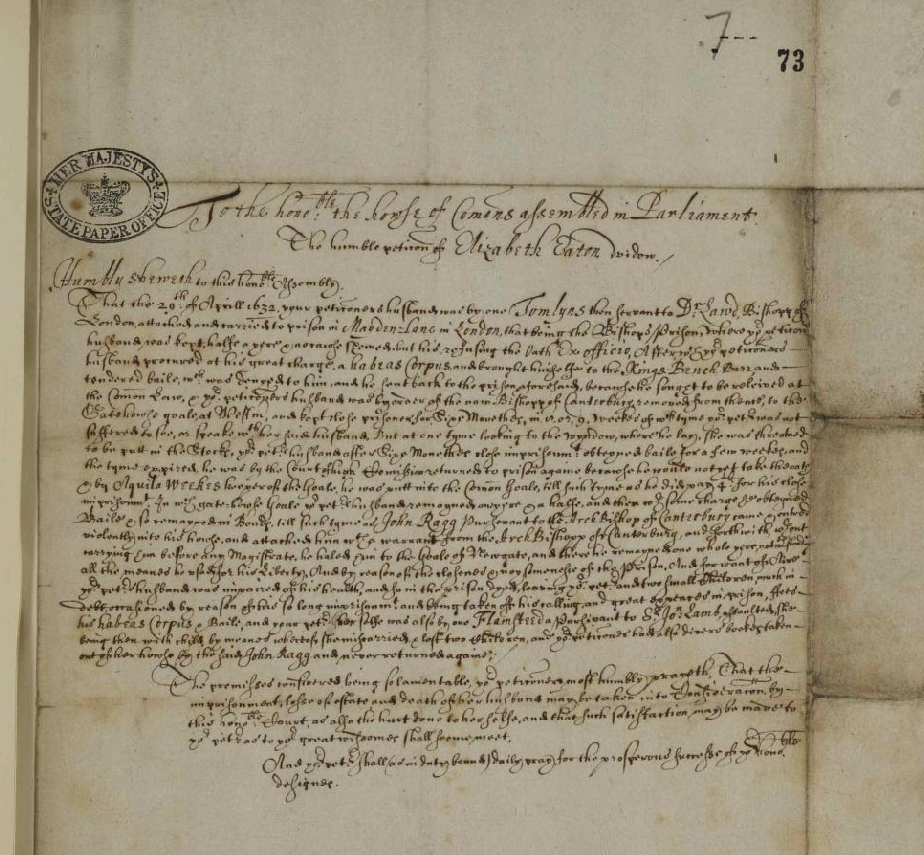

The homes of religious dissenters were constantly under siege. Men, women and children were routinely roused in the middle of the night, chivvied and dragged – at times quite literally – to be interrogated or thrown in prison. The result of such upheavals, if a woman was with child, could be miscarriage or a stillbirth. Elizabeth Eaton (fl. 1632–1641) was an active member of the Baptist Lathrop congregation in London who, along with several other women, was questioned by the High Commission court in the early 1630s. In 1641 she wrote a petition to the House of Commons (see Figure 1). Elizabeth explained that she was now a widow having lost her husband, Samuel Eaton (d. 1639) (who was also a Baptist), by his ‘wrongful imprisonment’. On one of several occasions that Samuel was arrested, Elizabeth describes how one John Ragg, Archbishop William Laud’s pursuivant, ‘violently entered his [Samuel’s] house and … haled him to Newgate’. Elizabeth, ‘being then with child’, was ‘assaulted by Flamsteed, a pursuivant to Sir John Lamb’, which ‘caused her to miscarry’. She was not alone in reporting such violence. Other women of the Lathrop congregation said that their own miscarriages were a result of the rough treatment they had received when arrested. Elizabeth’s petition clearly made an impression on the Commons. It was later included amongst papers relating to the trial of Archbishop Laud, as evidence of his excessive cruelty in prosecuting religious sectaries.

When a pregnant 18-year-old Elizabeth Bunyan (d. 1691), wife to the Baptist minister and author John Bunyan (bap. 1628, d. 1688), heard that her ‘husband was first apprehended’ in 1660, she was so ‘[di]smayed at the news’ that she ‘fell into labour’ at home for eight days. Soon after, in a petition she thrice delivered to Bedford judges to obtain her husband’s release, Elizabeth relates how she had given birth to an infant boy, but being stillborn, ‘my child [had] died’.[1] Her plangent pleas, however, did not convince enough of her auditors. Elizabeth’s harrowing account chimes with other cases of early modern neo-natal deaths that were caused by an equally traumatic ‘fright’ or event.

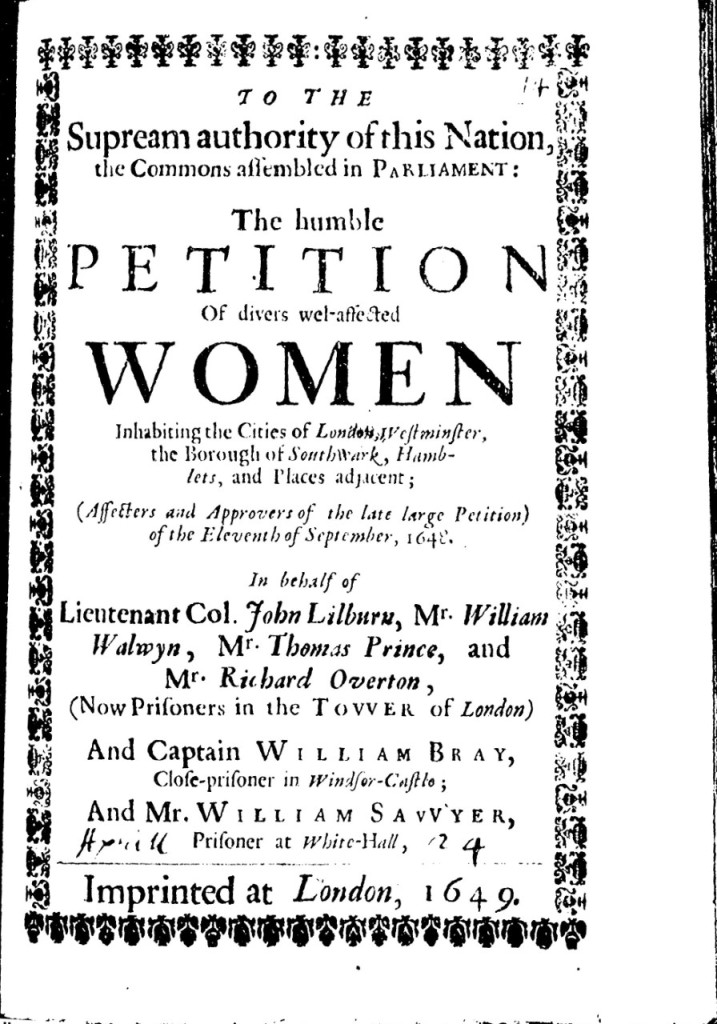

This was precisely the kind of harassment that one mass petition by Leveller women in 1649 was referring to whereby husbands were snatched ‘out of their beds, and forced out of their houses by Souldiers, to the affrighting and undoing of themselves, their wives, children’ (see Figure 2, my emphasis). Such documents reaffirm recent research into the vulnerability displayed, and sympathy commanded, by seventeenth-century petitions involving women which described physical trauma.

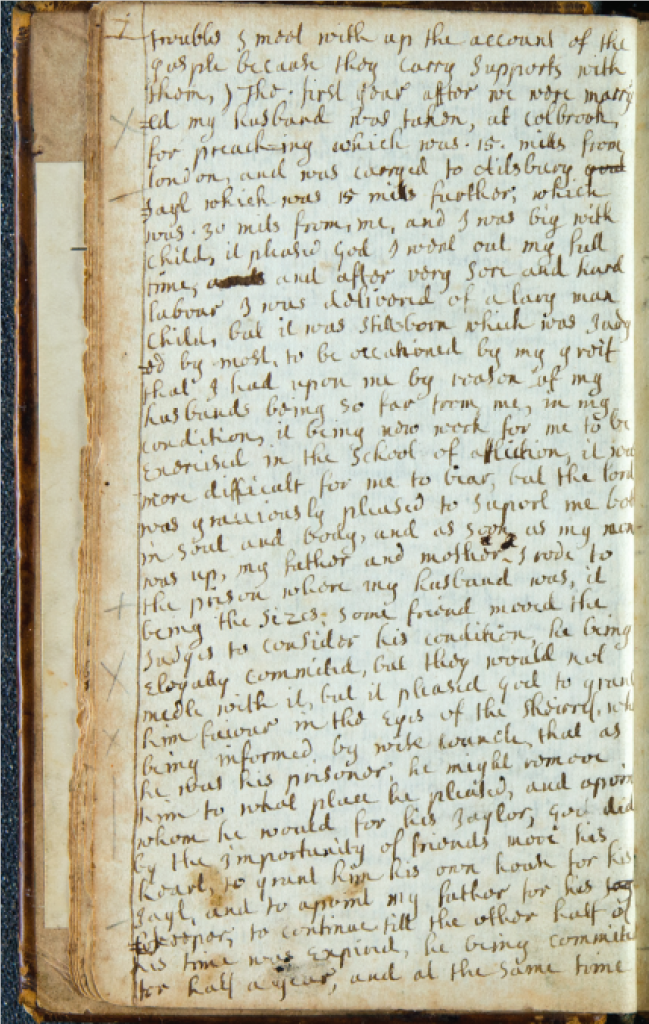

Married to a Presbyterian clergyman, Mary Franklin’s (d. 1711) spiritual autobiography also movingly recounts the personal loss she suffered at her London home during her family’s persecution after the Restoration (see Figure 3). Though this was written in manuscript, it, like the petitions by the two Elizabeths, had a potentially wide audience as it was read and circulated by succeeding generations of her own family and religious community. When her husband, the ejected minister Robert Franklin, (1630–1703), was taken to Aylesbury jail in 1670, Franklin records:

The first year after we were married my husband was taken at Colnbrook for preaching, which was fifteen miles from London, and was carried to Aylesbury jail which was fifteen miles further; which was thirty miles from me, and I was big with child. It pleased God I went out my full time, and after very sore and hard labor I was delivered of a large man-child, but it was still-born, which was judged by most, to be occasioned by my grief that I had upon me by reason of my husband’s being so far from me in my condition. It being new work for me to be exercised in the school of affliction, it was more difficult for me to bear.

Mary’s understandable anxiety over her husband’s arrest, coupled with the financial insecurity of having all her household ‘goods’ seized to pay the fine for breaching the Act of Uniformity (1662) – a devasting law which deemed her husband’s unlicensed preaching (his only means of income) illegal – was, in her own words, ‘difficult for me to bear’. Like Elizabeth Bunyan, Mary was inexperienced in married life, and also, like many younger wives of nonconformist preachers, inexperienced in the ‘school of affliction’. The result was a personal tragedy ‘which was judged by most’ to be avoidable.

More cases sadly followed and were publicised in printed pamphlets, broadsides and news-sheets. In October 1680, when authorities arrested the Quaker minister Elias Osborn (bap. 1643, d. 1720) and sixty-nine others at a meeting in Ilminster, Somerset, Osborn’s wife, Mary (d. 1675), ‘being then big with Child’, due to the shock of the situation ‘miscarry’d upon it’ when she returned home. Martha Webster (d. 1774), wife of John Nelson (bap. 1707, d. 1774), a Methodist preacher, suffered a miscarriage when she had been attacked by a mob at Wakefield in 1755. Regrettably, such examples could be replicated endlessly.

The emotional, physical and psychological abuse these women and their unborn children endured within and beyond their homes appears almost endemic to the experience of religious dissent during the post-Reformation era. In demanding that their suffering and child loss be recognized, seen as avoidable and thus reprehensible, women brought these domestic tragedies to the fore of the public sphere. Through printed pamphlets, repeated petitions, and circulated diaries, they maligned the idea that their voices belonged only to ‘household affaires’ and not ‘statematters’, affirming how infringements by the latter drastically and determinately effected the former. Though it is harder to chart how such accounts were read and received, the fact that many women engaged in literary and petitionary activities after such deeply personal losses speaks volumes to their determinacy, resiliency and political agency. Recovering and exploring such instances of child loss in the archive of religious dissenters may shed light on a darker history of persecution that is yet to be fully fleshed out.

Further Reading

Franklin, Mary, and Hannah Burton, She Being Dead Yet Speaketh: The Franklin Family Papers, ed. by Vera J. Camden (Toronto: Iter Press and the Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2020), pp. 131–52. Available here.

Howard, Sharon, ‘Women, gender and non-lethal violence in Quarter Sessions petitioning’, The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England (2020), available here.

Read, Sara, and Jennifer Evans, “‘Before Midnight she had Miscarried’: Women, Men and Miscarriage in Early Modern England”, Journal of Family History, 40 (2015), 3–23. Available here.

Thorne, Alison, ‘Narratives of female suffering in petitionary literature of the Civil War period and its aftermath’, Literature Compass, 10:2 (2013), 134-145. Available here.

[1] John Bunyan, ‘A Relation of My Imprisonment’, in Roger Sharrock (eds), John Bunyan: Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners (Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1963), 103–131 (p. 128).

This is an excellent topic. I hope you are/will send this to a journal soon. Although the trauma these women experienced is very possible and likely, should you consider the possibility that this was a trope to engender sympathy (e.g. the suffering of women, mothers).

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster