Our latest Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover post is by Tyler Rainford. Tyler is a first year PhD student at the University of Bristol, funded by the SWW DTP. His research focuses on alcohol consumption and Atlantic exchange in early modern England, 1650-1750. You can find him on Twitter @Tyler_Rainford

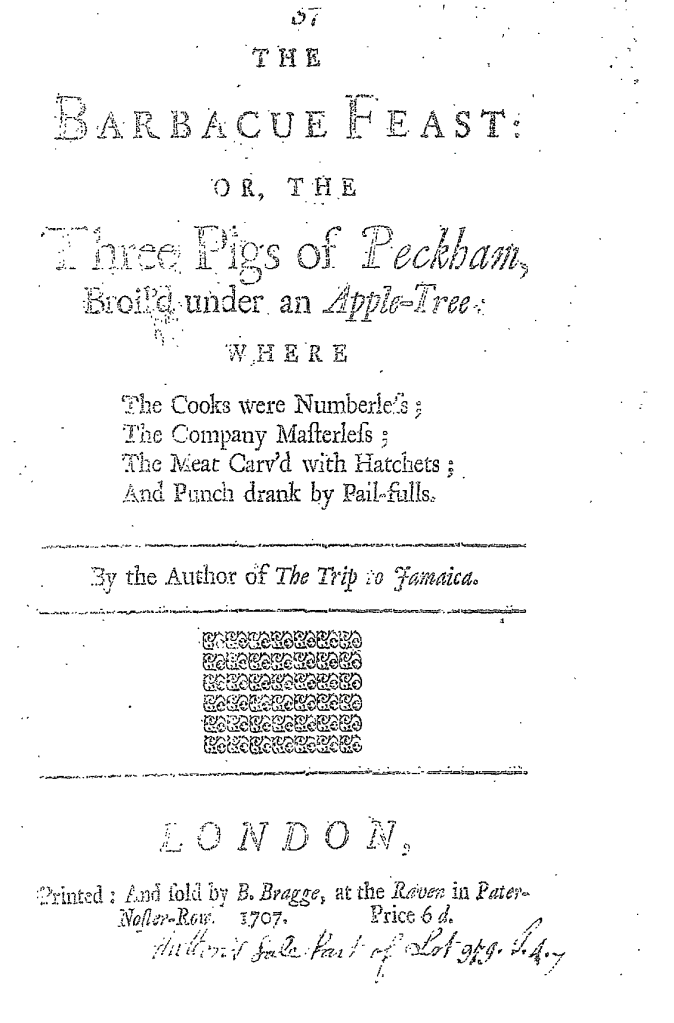

How did ordinary people experience colonial groceries in early modern England? Thanks to the pioneering work of Carole Shammas we now know that ‘being poor and being a consumer […] were not mutually exclusive conditions.’ Ordinary people were able to get their hands on an array of goods, which were previously believed to be the reserve of their betters (at least initially). But the way certain individuals and communities engaged with new commodities is often hard to articulate. It’s all too easy to imagine consumption as something that “trickles down” the social scale, as commodities became cheaper and more accessible. Take tea, for example. It is generally argued that tea drinking, at first a peculiar and exotic ritual, became popular amongst more elite and middling members of society, before making its way into the daily lives of ordinary women and men. But such a model hides a more complex reality. Colonial groceries and cooking techniques could be experienced first-hand by those we might consider “plebeian,” and the cultural influence of these goods could prove profoundly transformative. The Barbacue Feast: Or, The Three Pigs of Peckham, penned by Ned Ward in 1707 provides one such example.

Ward’s scintillating verse and prose provides a fascinating glimpse into the nature of urban life in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Best known for his opus, The London Spy, which originally appeared in the form of eighteen instalments between 1698 and 1700, Ward’s work is decidedly visceral. The Barbacue Feast is no exception. Unsurprisingly, food and drink take centre stage in Ward’s description of this distinctly raucous affair, and their sensational influence is apparent from the outset. Alcohol is so prominent that it acts as the catalyst for the whole event. Indeed, Ward describes how a jolly group of mariners from Rotherhithe in Southwark became so ‘over-heated with that West-India-Diapente, call’d Kill-Devil [Rum] Punch’ that their thoughts turned to another Caribbean treat:

‘… By the powerful Ascendancy of the American Tipple, their Natures were so wonderfully chang’d, and their English Appetites so deprav’d and vitiated, that nothing would satisfy the squeamish Stomacks of the fanciful Society but a Litter of Pigs most nicely cook’d after the West-India Manner.’

The intoxicating effect of rum punch was powerful enough to usher in a new set of thoughts and appetites amongst the mariners, rekindling experiences tasted across the Atlantic. The liquor’s inebriating influence lasted long enough for the merry band to liaise with a local alderman and organise a site for the feast in nearby Peckham, advertise and sell tickets for the event, and source the all-important pigs for the fire.

A few days (and a nasty hangover) later, the feast day itself had arrived and the company assembled, each with ‘whetted Knife, a sharp Stomack, and a Pair of nimble Jaws’ in feverish anticipation. The sight and smell of the broiling porkers caused another (metaphorical) transformation, with the participants at one point ‘expressing as much Joy in their Looks and Actions, as a Gang of wild Cannibals, who, when they have taken a Stranger, first dance round him, and afterwards devour him.’ Additionally, when Ward asked the participants why they drank their punch out of pails, a man suggested: ‘fore as it is a Pig-Feast, the more Hoggishly we are serv’d, the more agreeable.’ Human nature itself was temporarily suspended during the festivities. The unsettling metamorphosis from Englishman, to ‘savage’, to swine, is echoed continually throughout Ward’s narrative, suggesting that the intrinsic qualities contained within the food and drink present could transform and dehumanise those who consumed them.

The context surrounding the event is crucial to understand. This wasn’t a commonplace occurrence but a unique social event, engineered by a specific social group. The festivities described by Ward are undeniably carnivalesque and subversive in their character, with participants (depicted as) reverting to an almost primitive state, liberated from the traditional social bonds of English society. Indeed, the parodying of a traditional English feast day is complete with a mock prayer led by a ‘Man that we pitch upon for our Chaplain.’ Another man, ‘screweing up his Countenance to a very grave Pitch of Hypocrisy’ delivered a sermon on moderation before ‘strip[ping] off his Puritannical Habilements’ and becoming ‘as frolicksome as a Merry-Andrew,’ dancing for the company’s entertainment. Similarly, although there is evidence to the contrary within the text, Ward claims on his title page that the company was ‘Masterless,’ suggesting the very social order of English society had been suspended through the festivities, albeit temporarily. Although the food and drink may have been strange, the carnivalesque atmosphere was all too familiar. The colonial goods and cooking techniques may have been depicted as exotic and barbaric by Ward, but there is evidence to suggest they could be appropriated into more conventional social rites and rituals.

What’s interesting about the food and drink present here is that neither had been appropriated into the rituals of elite or middling groups. Barbecue, a Native American cooking technique, was virtually unknown in Europe, and this source is perhaps the earliest example of its application in England. Rum, a product of the Caribbean plantation system was a drink for servants, sailors, and slaves, described in 1651 as a ‘hott hellish and terrible liquor.’ In 1707, the liquor was still relatively unfamiliar to English palates. Both food and drink were first experienced (and appropriated in the case of barbecue) by ordinary people in a manner which largely ran counter to the emergent ‘civilising appetite’ of the age. The event was simultaneously a confirmation of the old, through the ritualistic feasting of an earlier age, and an acknowledgement of the new, through the use of colonial groceries and cooking techniques. The Barbacue Feast, therefore, is but one example of how England’s colonial enterprise could be interpreted and experienced by diverse social groups in unique and multifarious ways.

Further Reading:

Bakhtin, Mikhail, Rabelais and His World, translated from the Russian by Helene Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984).

Lemire, Beverly, “Men of the World:’ British Mariners, Consumer Practice, and Material Culture in an Era of Global Trade, c.1660-1800’, Journal of British Studies, 54 (2015), pp. 288-319.

Mennell, Stephen, All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press).

Shammas, Carole, The Pre-Industrial Consumer in England and America (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990).

Walvin, James, Fruits of Empire: Exotic Produce and British Taste, 1660-1800, (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997).

Pingback: Merkwaardig (week 17) | www.weyerman.nl

Pingback: The Early Career Researcher Takeover | the many-headed monster