Brodie Waddell

Gavin Robinson, over at Investigations of a Dog, asks ‘Why weren’t there any comics in the 1640s?’

He uses to the wikipedia definition:

a sequence of drawings arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often serialized, with text in balloons and captions

This seems rather strict for my taste. Perhaps this is the nature of wikipedia – an article on ‘comic books’ is bound to be dominated by comic ‘purists’ (even ‘puritans’) with a prescriptive outlook. The OED, in contrast, simply gives one definition of ‘strip’ as

A sequence of small drawings telling a comic or serial story in a newspaper, etc. Freq. as comic strip. Also transf. orig. U.S.

It gives the first use in 1920, which slightly predates the first supposed ‘comic book’ in 1933.

Apparently the first ‘comics’ (by the strict wikipedia definition) only appeared in the nineteenth century, and Gavin Robinson offers some possible reasons why, all of which seem plausible.

However, is it really true that ‘comics’ only emerged in the nineteenth century?

If we go by the OED definition, certainly not. As Gavin points out, ‘sequential art’ goes back to the Romans at least, and there are plenty of early modern examples. Here is Hogarth’s famous series:

William Hogarth, A Harlot’s Progress (1732). Image borrowed from here.

If we go by the wiki definition, we need ‘text in balloons and captions’, both of which are found in many early modern sources, but which was not normally paired with sequential panels. Here, for example, is some dialogue in balloons from a ballad in the Pepys collection:

All of this is just a lengthy prologue to my own attempt at a small contribution. Whilst I haven’t found anything that unambiguously matchs the narrow definition, I think this comes pretty damn close.

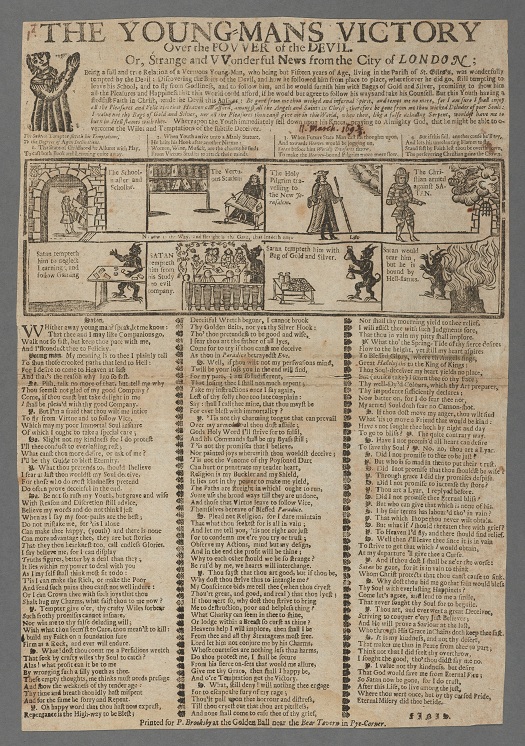

The Young-Mans Victory Over the Povver of the Devil Or Strange and VVonderful News from the City of London (?1693), from the Haughton Library at Harvard.

I came across this broadsheet when looking for an image for the cover of my book. You’ll note that although it doesn’t have dialogue in balloons, it does tell a sequential story through pictorial panels with accompanying in-panel text.

Detail of panels from The Young-Mans Victory Over the Povver of the Devil Or Strange and VVonderful News from the City of London (?1693).

My favourite panel (and the one that ended up on my book cover) is that which shows the devil trying to tempt the ‘Young-Man’ with ‘Bag of Gold and silver’. It makes literal the age-old association between ‘gold’ (i.e. riches) and ‘temptation’ (i.e. sin and damnation), neatly encapsulating one of my arguments: traditional Christian moral codes continued to be a popular way to think about economic life at the end of the seventeenth century.

So, is this an early modern comic strip?