In the spring of 2020, as much of the world was plunged into ‘lockdown’ by the advance of a global pandemic, regular forms of face-to-face interaction were swiftly replaced by online alternatives. We all found ourselves coming up with new ways to recreate our scholarly activities online, as the classroom morphed into the online seminar; the conference trip was replaced by a day tucked away in a corner of the bedroom staring at Zoom; the common-room catch-up was transferred to the Departmental WhatsApp group.

As the UK lockdown eased at the end of June, we invited our readers to contribute to this ongoing mini-series reflecting on the best way to build communities online.

Contents

> Laura Sangha & Mark Hailwood, ‘The Virtual Parish: Scholarly Communities Online’

Laura and Mark introduce the series and reflect on eight years of running this blog as an online scholarly community. What do we gain from taking our conversations online? What do we lose? What needs to be improved?

> Will Pooley, ‘Online Conferences: Four Reflections’

Will examines his experience of co-organising an online Zoom conference during a global pandemic. He discusses how things were adapted, what online spaces had to offer, and accessibility.

> Clare Griffin, ‘Time Zones Still Exist’

Many of us are facing the prospect of teaching across time zones in the autumn of 2020. Here Clare Griffin reminds us of the access implications of time zones for online events, and suggests that the move online could provide an opportunity to improve the experience of delegates across the globe.

> Jennifer Farrell, ‘The Digital Delegate: attending on online international conference’

What is it like to attend a huge international conference from the comfort of your own home? Jennifer considers reduced costs, technology, trolls and community.

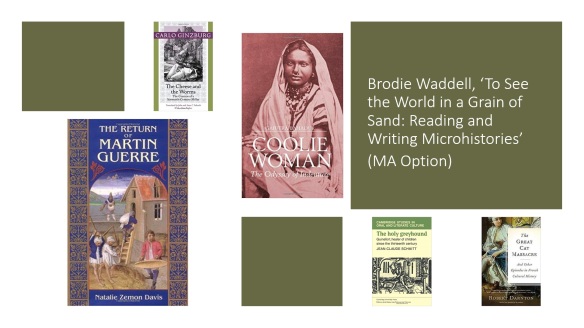

> Brodie Waddell, ‘Teaching Microhistory: small things, big questions and a global pandemic’

How can we teach students the value in studying small things to answer big questions, online, during a pandemic? Brodie explains what it was like to teach an online MA module on theory and methodology, and gives away the handbook for free!

> Elizabeth Watts, ‘Evading the Hounds: Online Scholarly Collaboration and Crowd Sourced Harrassment’

Taking our scholarly communities online has opened up a world of conversation. Yet in grounding our collaboration in spaces which are subject to rampant organised harassment and surveillance, the well-known threats that marginalised scholars at in-person events face from individuals are exchanged for the instantaneous threat of abuse at menacing, escalating scale. In this post Elizabeth shares her own experience as a victim of online of such online abuse.

> Marianne C.E. Gillion, ‘Cultivating a (Virtual) Conference Community

Marianne discusses what it was like to rise to the challenge of hosting a major conference online. The 2020 Medieval and Renaissance Music Conference created a virtual environment that facilitated the unique combination of scholarship, music, networking, and the sociability integral to the annual event.

> Laura Sangha, “‘You’re on mute!’: How can we make online meetings better?”

Online meetings have become a common feature of our working lives this year, but many people are frustrated at the amount of time they take up. How do they compare with a face-to-face version – beyond the potential technical pitfalls, might they be an improvement? And what can we do to make them more accesible, inclusive and effective?

> Brodie Waddell, ‘How are we going to teach in Autumn 2020? A Survey of UK Historians.

It’s August, but in many UK institutions there is still much uncertainty about what form teaching will take when term starts next month. Here Brodie offers some thoughts based on a quick informal survey of scholars based in 26 different UK history departments, asking them what proportion of teaching they are planning to conduct face-to-face in the autumn.

> Mark Liebenrood, ‘Serendipities of Online Community’

In this post Mark Liebenrood reminds us that serendipity is not the preserve of archival research: it can be one of the great strengths of online scholarly communities too.