[In our mini-series ‘A Page in the Life’, each post briefly introduces a new writer and a single page from their manuscript.]

Laura Sangha

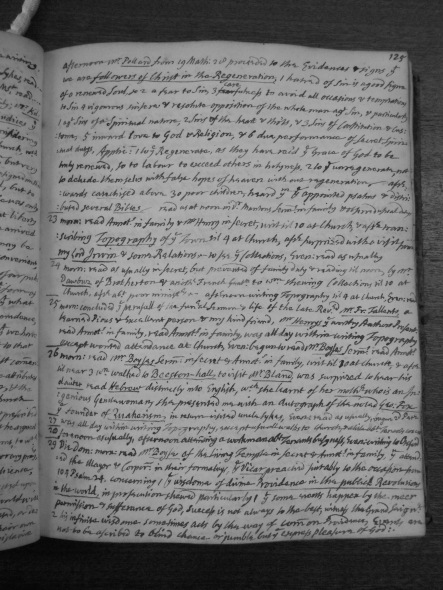

The Leeds antiquarian and pious diarist Ralph Thoresby (1658-1725) wrote a lot. An awful lot. Between the ages of nineteen and sixty-seven he kept a diary, often recording entries on most days of the week. Seven volumes of Thoresby’s life-writing survive, and at approximately 500 pages per volume that’s 3,500 pages of text. The page transcribed below is fairly typical at 550 words, so that makes close to two million words of Thoresby’s self-reflection out there. You don’t have to read them all though, because this page below provides a relatively good sense of the content and scope of Thoresby’s written self:

The Leeds antiquarian and pious diarist Ralph Thoresby (1658-1725) wrote a lot. An awful lot. Between the ages of nineteen and sixty-seven he kept a diary, often recording entries on most days of the week. Seven volumes of Thoresby’s life-writing survive, and at approximately 500 pages per volume that’s 3,500 pages of text. The page transcribed below is fairly typical at 550 words, so that makes close to two million words of Thoresby’s self-reflection out there. You don’t have to read them all though, because this page below provides a relatively good sense of the content and scope of Thoresby’s written self:

Brotherton Library, Yorkshire Archaeological Society MS 24.

[22 May 1709][1]

afternoon Mr Pollard from 19 Math:28 proceeded to the Evidences & signs that we are followers of Christ in the Regeneration, 1 hatred of sin is a good signe of a renewed Soul, so 2 a fear to Sin, 3 carefulness to avoid all occasions and temptations to Sin 4 vigorous sinsere & resolute opposition of the whole man against Sin, & particularly 1 against sins of a spiritual nature, 2 Sins of the heart and tho’ts, & 3 Sins of Constitution & Custome, 5 inward love to God & Religion, & 6 due performance of secret Spiritual dutys, Application: 1 to the Regenerate, as they have rec’d the Grace of God to be truly renewed, so to labour to exceed others in holiness, 2 to the unregenerate, not to delude themselves with false hopes of heaven with out regeneration – afterwards catechised above 30 poor children, heard them the appointed psalms & distributed several Bibles – Read as at noon in Dr. Mantons Sermons in family & observed usual duties

23 morn: read Annotations in family & Mr Henry in secret, writ til 10 at Church, & after transcribing Topography of the Town til 4 at Church, after surprized with a visit from my Lord Irwin & some Relations, to see the Collections, Even: read as usually Continue reading