This is the fourth guest post in the mini-series Visual Culture in Early Modern England (read the introduction and find links to other posts here). Adam Morton shares his experience of using images to get students talking in seminars, exploring their ability to get students thinking about things like opinion, polemic and ambivalence in primary material.

Adam Morton is Reader in Early Modern British History at Newcastle University. He researches the long-Reformation in England, with a particular focus on anti-popery and visual culture. His publications include Civil Religion in the early modern Anglophone World (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) (with Rachel Hammersley), The Power of Laughter & Satire in Early Modern Britain: Political and Religious Culture, 1500-1820 (Boydell & Brewer, 2017) (with Mark Knights), Queens Consort, Cultural Transfer and European Politics, c.1500-1800 (Routledge, 2016) (with Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly), and Getting Along? Religious Identities and Confessional Relations in Early Modern England – Essays in Honour of Professor W.J. Sheils (Routledge, 2012). His current project considers the visual culture of intolerance in early modern England.

Adam Morton

I’ve always found that images get History students talking. They see things I don’t see and ask questions I’ve not thought to ask. The chattiest students are often the ones I least expect, the ones who have been quiet in previous weeks, the ones you worry are struggling with or not enjoying the course. Approaching a seminar topic through images can bring those students out of themselves.

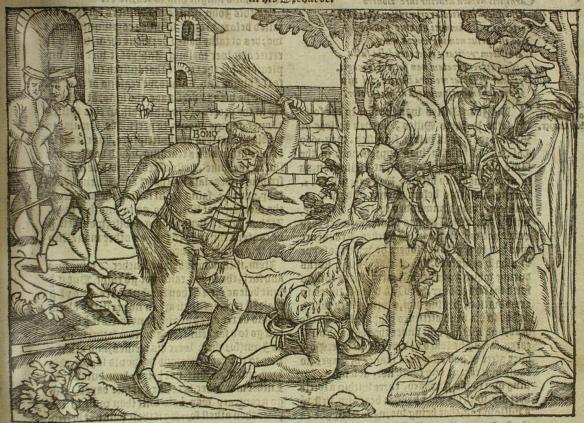

I remember one instance, long ago on a second year Reformation course timetabled in the drabness and drizzle of the autumn term’s Friday afternoon slot, with fondness. A woodcut from John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments showing Edmund Bonner, the Bishop of London, stripped to his underwear and thrashing a Protestant’s buttocks, left one usually quiet student tripping over her tongue with things to say [Fig. 1].[1] She prodded the seminar to life with thoughts about humour, about cruelty and humiliation, about images as acts of revenge, and about the control involved in having the power to portray someone. Long dead Reformers suddenly seemed very human to her. “Is the image sexual?”, she asked the room. The discussion took off. Now I was the silent one: the teaching was going well.

Foxe’s woodcuts are an obvious candidate for primary sources in undergraduate seminars, of course. Although they are no longer as rooted in public life as firmly as they were two generations ago, ‘The Book of Martyrs’’ images still provide a way into the big problems of Reformation history in the seminar room because they offer us dramatic vignettes that pare abstractions – martyrdom, heresy, theology, and memory – down to something tangible. But images can be much more than ice breakers. They can be the bedrock of seminar discussion, too. Continue reading