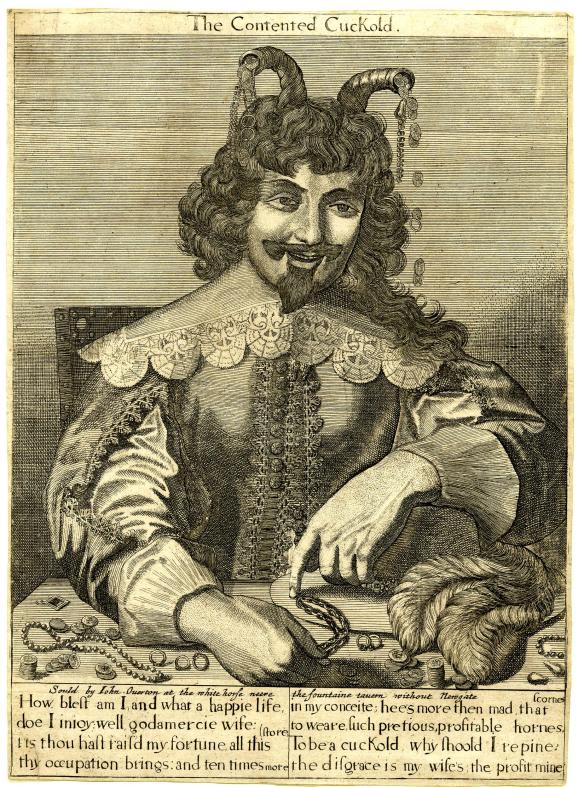

This is the first guest post in the new monster mini-series Visual Culture in Early Modern England (read the introduction here). To begin, Adam Morton considers what historians should do with the alien and often cruel humour of past ages and in particular the subversive content of satirical prints.

Adam Morton is Reader in Early Modern British History at Newcastle University. He researches the long-Reformation in England, with a particular focus on anti-popery and visual culture. His publications include Civil Religion in the early modern Anglophone World (Boydell & Brewer, 2024) (with Rachel Hammersley), The Power of Laughter & Satire in Early Modern Britain: Political and Religious Culture, 1500-1820 (Boydell & Brewer, 2017) (with Mark Knights), Queens Consort, Cultural Transfer and European Politics, c.1500-1800 (Routledge, 2016) (with Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly), and Getting Along? Religious Identities and Confessional Relations in Early Modern England – Essays in Honour of Professor W.J. Sheils (Routledge, 2012). His current project considers the visual culture of intolerance in early modern England.

Adam Morton

Old jokes unsettle me. Not only because I don’t always get them, but because the ones I do get are often brazenly cruel. They mock, scoff, and jeer at the butt of the joke in a laughter of scorn and humiliation. This cruelty unsettles me because humour is intimate, it speaks to the most human aspects of a culture, the intimate ties, social bonds, and moral norms that glue people into a society. We laugh when something disrupts or breaks those conventions, and laughter therefore takes us close to what made people in the past tick, their assumptions about the world, their emotions, and their view of what was proper.[1]

Laughter, in short, is intuitive, something that Clive James captured succinctly. “Common sense and a sense of humour are the same thing moving at different speeds. A sense of humour is common sense, dancing”. Early modern people? Their ‘common sense’ led them to laugh at rape victims, at the disabled, at those who experienced devastating misfortune, and at domestic violence, among other cruelties.[2] Studying humour takes us closer to early modern people. I am unsettled because I don’t always like what I see.