In this guest post Dr Peter K. Andersson reflects on the challenges of trying to write a biography of Henry VIII’s court fool, Will Somer. Dr Andersson is based at Örebro University in Sweden and works on the history of fools and clowns from the early modern to the modern age. His previous research has looked at Victorian streetlife and popular culture from below.

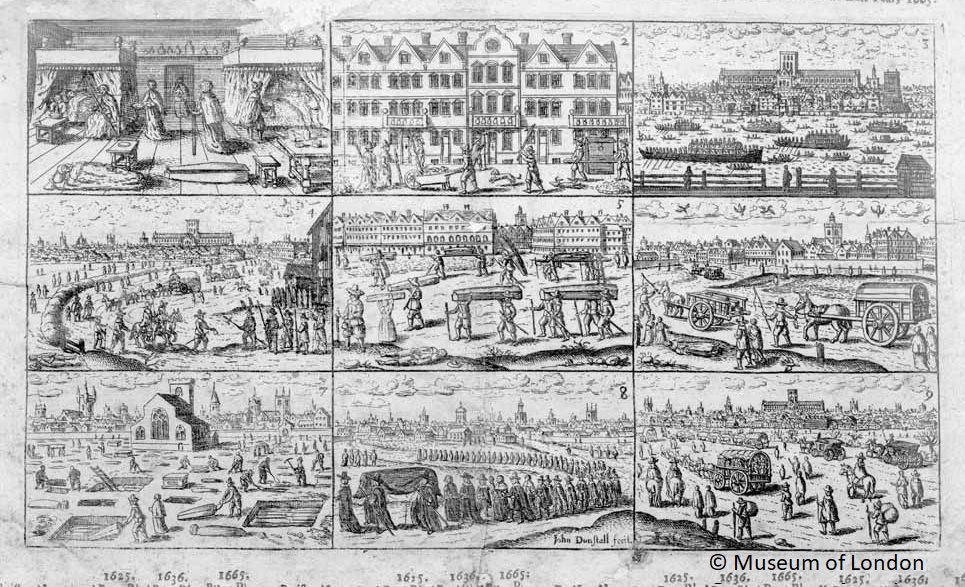

It’s strange to think that among the people who were closest to King Henry VIII was a man who, by all accounts, was a humble commoner and possibly intellectually disabled. In the early modern period, there was virtually only one way in which a person of low birth from a poor background could become close to a monarch and spend as much time with him or her as their family members. Naturally, it was possible for a commoner to enter the royal household as a servant, but I think it’s safe to say that there was only one occupation that transgressed the social hierarchy in such an extreme way. I am, of course, referring to the position of court fool.

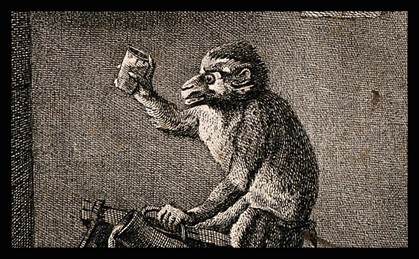

There were many hundreds of court fools and jesters from the Middle Ages until well into the eighteenth century, and most of them enjoyed a status not far from that of a stable boy or scullery maid, or, at the other end of the spectrum, a hired entertainer living at best close to the court, but only seeing the king when called for to entertain. One of the most famous fools in all of history, however, appears to have lived as close to the monarch as possible, and he did so for an unusually long time.

To posterity, his name is often known as Will Summers, or Sommers, but this spelling only really emerges after his death. To his contemporaries, he was Will, or William Somer – sometimes with an -s added. During the sixteenth century, he grew to become one of the most legendary comics of the age, and after his death turned into a recurring folk hero, cropping up in ballads, jestbooks and pamphlets – not to mention plays, most famously by Thomas Nashe and Samuel Rowley. When Shakespeare omitted him from his play about Henry VIII, he had to include a prologue that explained to the audience that they would not be seeing the beloved fool, so as not to force anyone to sit through it waiting for him to come on.

Continue reading