Brodie Waddell

In 1658, the Czech scholar John Amos Comenius published what’s been called ‘the first children’s picture book’. It proved extremely popular and was republished many times, in many different languages. What brought it to my attention was the fact that it included 150 pictures of ‘the visible world’, a rare treat in an early modern publication.

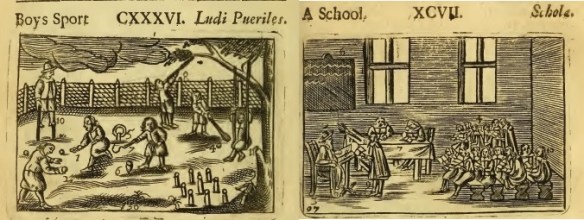

It was designed to teach Latin and, in the 1705 edition, English to young people, so most of its illustrations depicted the sorts of things a child might be expected to know from life. They would find, for example, pictures of youth at study and at play, stilt-walking or bowling.

However, the ones that caught my eye were the many illustrations of working life. If you, like me, teach or write about early modern economic history, you’ll know that this particular subfield has an ‘image problem’. Perhaps thanks to a strong seam of ‘iconophobic’ Calvinism, post-Reformation England was not exactly awash in imagery of any kind and I have often found it particularly difficult to find images of economic life. One can find many pictures of kings and noblemen. But there are frustratingly few depictions of ordinary people doing their jobs, whether as artisans, traders or labourers. This gap is partly filled by the broadside ballad woodcuts on EBBA that Mark Hailwood has discussed here before. However, it remains difficult to find the sort of rich visual material that one can find, for instance, in Dutch ‘Golden Age’ paintings or in nineteenth-century periodicals. Continue reading

However, the ones that caught my eye were the many illustrations of working life. If you, like me, teach or write about early modern economic history, you’ll know that this particular subfield has an ‘image problem’. Perhaps thanks to a strong seam of ‘iconophobic’ Calvinism, post-Reformation England was not exactly awash in imagery of any kind and I have often found it particularly difficult to find images of economic life. One can find many pictures of kings and noblemen. But there are frustratingly few depictions of ordinary people doing their jobs, whether as artisans, traders or labourers. This gap is partly filled by the broadside ballad woodcuts on EBBA that Mark Hailwood has discussed here before. However, it remains difficult to find the sort of rich visual material that one can find, for instance, in Dutch ‘Golden Age’ paintings or in nineteenth-century periodicals. Continue reading