Brodie Waddell

Busy though I may be, I can’t help but note the death of Eric Hobsbawm and offer a few thoughts.

No doubt our readers will already be familiar with Hobsbawm and his work. If not, the lengthy obituary in the Guardian or this article by the historian Mark Mulholland will make clear his perhaps unmatched contributions to historical knowledge, both popular and academic.¹

Eric Hobsbawm at his typewriter. Source: John Brown via Jacobin.

Rather than recount his fascinating life or delve into his most famous works, I’d like mention how he (unknowingly) touched my life at a couple of important moments.

The first took the form of his book Uncommon People: Resistance, Rebellion and Jazz (1998) which I received as a gift for, I believe, my seventeenth or eighteenth birthday from my infinitely thoughtful uncles. At the time, I was vaguely interested in history but my contact with truly artful historical writing was negligible. Then I opened this book and found an essay entitled ‘Political Shoemakers’:

The political radicalism of nineteenth-century shoemakers is proverbial. Social historians of a variety of persuasions have described the phenomenon and assumed it needed no explanation. A historian of the German revolution of 1848, for example, concluded that it was “not accidental” that shoemakers “played a dominant role in the activities of the people”. Historians of the “Swing” riots in England referred to the shoemakers’ “notorious radicalism” and Jacques Rougerie accounted for the shoemakers’ prominence in the Paris Commune by referring to their “traditional militancy”. Even so heterodox a writer as Theodore Zeldin accepts the common view on this point. The present paper attempts to account for the remarkable reputation of shoemakers as political radicals.²

The essay goes on to provide plenty of colourful examples drawn from across the globe, but by the time I’d read the first sentence I was already hooked. The image of the militant shoemaker, writing radical manifestos and taking to the barricades, was simply too wonderful for a nerdy teenager to forget.³

Not long after receiving Uncommon People, perhaps in my first or second year as an undergraduate, I came across his Primitive Rebels (1959) in a used book store. I think this may have been the first time I found a work of history that was not only interesting and politically appealing, but also made an important argument about the nature of past societies. Indeed, the book almost single-handedly created a whole new analytical category: ‘social crime’.⁴ I’m not going to claim it was the light on the road to Damascus that turned me into a budding historian, but in retrospect I think it helped to push me in that direction. It’s no accident that the undergrad module I put together for this year includes a week focusing on the debate that this concept spawned.

Hobsbawm’s writing room, reassuringly messy. Source: Eamon McCabe via the Gaurdian.

And then, many years later, whilst looking around for something to do at the expiration of my fellowship at Cambridge, imagine my delight at being invited for an interview for a post at Birkbeck. Founded in a tavern as the London Mechanics’ Institute back in 1823, this was the place that Hobsbawm made his academic home when become a lecturer there in 1947. He was still its nominal President when I applied there last year and, despite being in his nineties, my colleagues recount vivid memories of him still occasionally strolling into the department to chat and of course frequently showing up at conferences to engage in conversation (and disputation) with historians less than half his age. I am saddened to have never met him myself, but I hope that in some very small way I can help carry on his legacy at this wonderfully unusual institution.

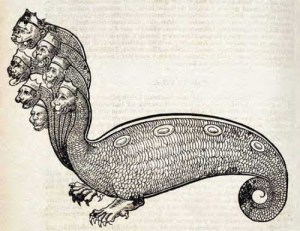

I would be very curious to hear how some of the monster’s other heads or perhaps some of our readers encountered Hobsbawm’s work. Does anyone have any stories to share?

Footnotes

¹ See also this nice little collection of quotations from the great man himself. The final one ‘On his writing room’s bookshelves’ is particularly pleasing.

² ‘Political Shoemakers’ was co-authored with Joan Wallach Scott and originally published in Past & Present, no. 89 (1980), pp. 86-114

³ Note that this also means, strangely, that I read Hobsbawm before reading E.P. Thompson or Christopher Hill, two other members of the Communist Party Historians Working Group, whose work I cite infinitely more often.

⁴ The Wikipedia article on ‘social bandits’ isn’t bad, but for a more detailed recent discussion, see John Lea, ‘Social Crime Revisited’, Theoretical Criminality, 3:3 (1999) [ungated]. For early modernists, the work on this by Douglas Hay, Peter Linebaugh and E.P. Thompson, especially but not exclusively Albion’s Fatal Tree (1975) and the responses it provoked, is essential reading.