[In our mini-series ‘A Page in the Life’, each post briefly introduces a new writer and a single page from their manuscript. In this post, Dr Robert W. Daniel of the University of Warwick offers us insights into the diary of the Church of England clergyman Isaac Archer and his experiences of preaching whilst ill. Robert is a Post-Doctorate researcher and General Secretary of the International John Bunyan Society. Follow him at @BunyanSociety]

25 of September [1679] in the night I had an hott fitt of an ague…

28 [September]… [ague] not so bad; and on October 1 worse…

[13 October] Munday discovered it selfe a quartane, which continues stil…

1st [December?], for a fortnight, ’twas tedious [the ague], but I went to Isleham, and tooke physick, and then it shortned, and now I can bear it, only I am not able to preach…

December 25. I ventured to preach, and so onwards

February 12 [1680]. I have the ague stil… I can officiate [in church]

March 10. I tooke a small journey, and came home wett, upon which my ague came that night… I ventured to preach twice for about a month, but gatt hurt, and my speech was difficult, and my breath shorter than ever I knew it… I agreed to preach only in afternoons…[1]

These are the entries that appear in a page of the diary of the Church of England clergyman Isaac Archer (b. 1641, d. 1700) when he was the resident vicar at Freckenham, Suffolk. His efforts to preach whilst suffering from a nine-month ‘ague’ (likely malaria) are astonishing in part because these attempts, whilst sporadic, were potentially fatal.[2] His sickly preaching exacerbated serious respiratory difficulties which must have been quite unsettling.In light of the recent CFP from the Ecclesiastical History Society on, ‘The Church in Sickness and in Health‘, I was struck by Archer’s experience of illness, and was left with some nagging questions. Did he often preach when ill? If so, what other ailments did he experience while officiating in church? Did he take any sick days? How did Archer rationalize risking his health to preach God’s Word? In this blog post I will attempt to answer some of these questions by examining the motivations and occasions of Archer’s sickly pulpit exertions. Doing so may tell us something surprising about the convictions of, and cost incurred by, England’s pulpiteers.

Continue reading

After a brief mid-term hiatus, in this last post marking the publication last month of my latest monograph,

After a brief mid-term hiatus, in this last post marking the publication last month of my latest monograph,

Nowhere was this aspect of ‘making it up as they went along’ more visible than in discussions of the Eighth Commandment – for while certain sins were pretty much universals of human nature (sins of violence and lust, for example) the realities of economic life in sixteenth century England were very different from those of the ancient Middle East.

Nowhere was this aspect of ‘making it up as they went along’ more visible than in discussions of the Eighth Commandment – for while certain sins were pretty much universals of human nature (sins of violence and lust, for example) the realities of economic life in sixteenth century England were very different from those of the ancient Middle East.  The Seventh Commandment, ‘Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery’, was one of the most commented upon in the whole Decalogue. ‘Adultery’ was quickly expanded by Protestant authors to include all forms of ‘uncleanness’, in thought, word and deed, alone and with other humans and creatures, both in and outside of wedlock. Fornication, buggery, masturbation and bestiality were some of the headline crimes, but authors also sought to proscribe all ‘occasions’ and ‘enticements’ to sins of the flesh, including mixed dancing, excess consumption of food and alcohol, as well as lewd pictures, cosmetics, alluring gestures and coquettish glances. In contrast to such filthy living, the commandment enjoined chastity, both in and out of marriage: ‘immoderate use of the marital bed’ was as much a sin as pre- and extra-marital sex.

The Seventh Commandment, ‘Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery’, was one of the most commented upon in the whole Decalogue. ‘Adultery’ was quickly expanded by Protestant authors to include all forms of ‘uncleanness’, in thought, word and deed, alone and with other humans and creatures, both in and outside of wedlock. Fornication, buggery, masturbation and bestiality were some of the headline crimes, but authors also sought to proscribe all ‘occasions’ and ‘enticements’ to sins of the flesh, including mixed dancing, excess consumption of food and alcohol, as well as lewd pictures, cosmetics, alluring gestures and coquettish glances. In contrast to such filthy living, the commandment enjoined chastity, both in and out of marriage: ‘immoderate use of the marital bed’ was as much a sin as pre- and extra-marital sex. The four short monosyllables of the Sixth Commandment – thou shalt not kill – were therefore stretched and twisted by expositors of the Decalogue into some quite astonishingly intricate patterns, which reflected the religious and moral climate of the day. The godly vicar of Ryton, Francis Bunny, explained that the commandment forbade killing with hand, heart and tongue, ‘and all the things that tend to the hurt of any mans person’, including bereaving him, spoiling his goods and possessions, or omitting ‘such duties, as tend to the safety or good of other men’.

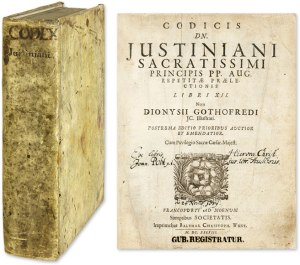

The four short monosyllables of the Sixth Commandment – thou shalt not kill – were therefore stretched and twisted by expositors of the Decalogue into some quite astonishingly intricate patterns, which reflected the religious and moral climate of the day. The godly vicar of Ryton, Francis Bunny, explained that the commandment forbade killing with hand, heart and tongue, ‘and all the things that tend to the hurt of any mans person’, including bereaving him, spoiling his goods and possessions, or omitting ‘such duties, as tend to the safety or good of other men’. The Fifth Commandment was the first precept in the Second Table of the Reformed Decalogue, heading the list of precepts which ordered man’s relationship with his fellow man. The Edwardian reformer and Bishop of Gloucester John Hooper, in his Declaration of the Ten Commandments of Almighty God, explained that in the Second Table ‘is prescribed how, and by what means, one man may live with another in peace and unity in this civil life, during the time of this mortal body upon the earth’. None of the great lawmakers of the classical world – Lycurgus, Plato, Cicero, Constantine, Justinian – individually or together had ‘prescribed so perfect and absolute a form of a politic wealth, as Almighty God hath done unto his people in this second table and six rules’.

The Fifth Commandment was the first precept in the Second Table of the Reformed Decalogue, heading the list of precepts which ordered man’s relationship with his fellow man. The Edwardian reformer and Bishop of Gloucester John Hooper, in his Declaration of the Ten Commandments of Almighty God, explained that in the Second Table ‘is prescribed how, and by what means, one man may live with another in peace and unity in this civil life, during the time of this mortal body upon the earth’. None of the great lawmakers of the classical world – Lycurgus, Plato, Cicero, Constantine, Justinian – individually or together had ‘prescribed so perfect and absolute a form of a politic wealth, as Almighty God hath done unto his people in this second table and six rules’.