Mark Hailwood

In this second of three posts introducing some key theoretical concepts through the history of food and drink (see here for the first) I’m going to move on to think about some of those borrowed from sociologists. The last post ended by stating that a concern with change over time plays an important role in the types of theories historians tend to like and dislike: and it helps to explain why they have been taken with our next key concept – the notion of the ‘civilising process’.

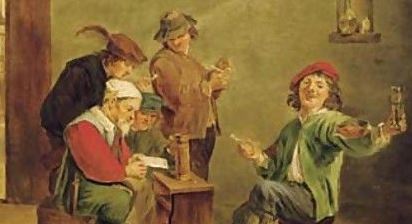

This was a theory first posited by the German sociologist Norbert Elias, back in 1939, but its main impact on Anglophone historians only came when it was translated into English in 1969, as: The Civilizing Process, Vol. 1: The History of Manners (1969). Its central claim was that between the middle ages (c.800AD) and the nineteenth century the manners of Europeans had become gradually more ‘civilised’ – by which he didn’t necessarily mean ‘better’ or more ‘progressive’ (he wasn’t passing judgement) but marked by increasing levels of self-restraint and self-control, especially with regards to violence, sexual behaviour, bodily functions, table-manners and forms of speech. By reading conduct manuals – guides to appropriate forms of social etiquette, a very popular genre – from across these centuries, Elias identified a shift away from an aristocratic honour culture in the middle ages which had seen aggression, violence, and the excessive consumption of food and drink as acceptable and laudable, towards an increasing sense of shame and repugnance towards all of these behaviours. Continue reading