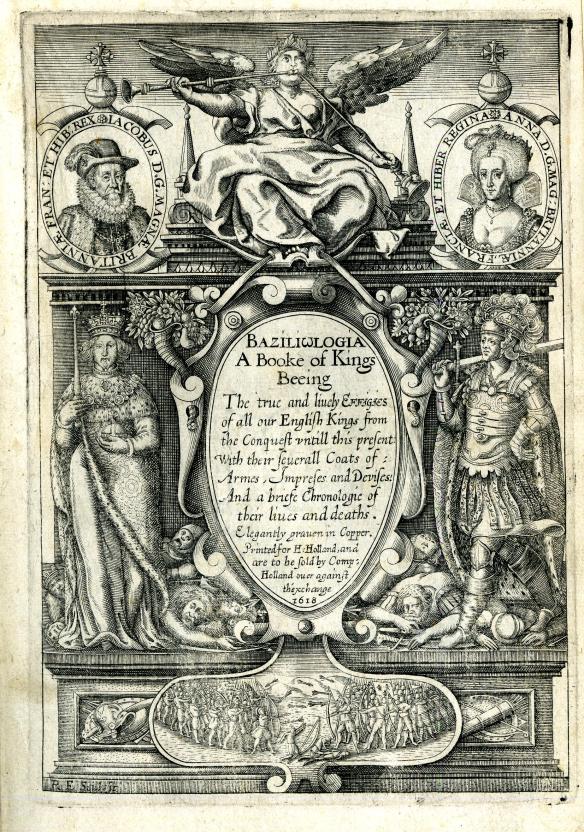

This post is part of a series that marks the publication of The Experience of Work in Early Modern England. The book is co-authored by monster head Mark Hailwood, along with Jane Whittle, Hannah Robb, and Taylor Aucoin. It uses court depositions to explore everyday working life between 1500 and 1700, with a particular focus on how gender shaped work. It is an open access publication (i.e. it is available to view/download for free, here). The post first appeared on the ‘Women’s Work in Rural England, 1500-1700′ blog as a ‘work in progress’ piece in 2019 – it is reposted here to whet your appetite for finding out where the research ended up, which you can do by reading the book!

Mark Hailwood

As Clare Leighton put it so elegantly in her 1933 The Farmer’s Year, it is that time of year when ‘summer begins to tire’. For centuries of farmers it has been the time when ‘the supreme moment of his year is upon him’, and across the ‘vast sweep of landscape there is the golden glow of harvest.’ It is August, and ‘harvesting is due’.

Of course, it is not only the supreme moment of the year for the individual farmer: for our preindustrial forebears the harvest was, as Steve Hindle has put it, ‘the heartbeat of the whole economy’.[1] The economic fortunes of early modern societies were bound up with the quality and quantity of grain gathered from the fields at summer’s end.

The importance of the early modern harvest, a process so evocatively captured by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1565, can hardly be overstated, and when the time came to set it in motion it dominated men’s work schedules above all else: ‘the harvesting draws all men to it. Ploughboy and cowman, carter and shepherd, all are in the fields’ (Leighton again). But what of the role played by women in the ‘supreme moment’ of the agricultural cycle? It is another question our project can shed some light upon.

Continue reading