Laura Sangha

For the past few years, I have been asked to contribute to a postgraduate training session on ‘Preparing to write’ which I deliver jointly with a professor in the English department. It is something that I really enjoy doing, because it is a chance to compare my own experiences and practice with other researchers. And each year I am struck anew by the similarities in the way that we approach our research, as well the fact that there are always new techniques and ways of working out there that I haven’t considered. Whilst the English professor has a complicated system of index cards and quotations, I tend towards colour-coded excel spreadsheets, both of which methods have something in common with Keith Thomas’ labour (and envelop) intensive working practices. The informal and inclusive nature of the discussion of the training sessions are a great way to encourage reflection on our working practice, many of which seem to organically emerge and ossify throughout our training and early career.

Excel is currently my favourite note taking tool.

Alongside thinking about preparing for writing, I have just bashed out my first paper on my new research into Ralph Thoresby, and found this blog post on what we might mean by ‘pace’ in writing incredibly useful for thinking about the processes involved. Recently Matt Houlbrook’s lyrical photo essay/ biography of a book chapter had also set me wondering just how similar our experiences are when it comes to writing. Does everyone feel the same deep unease [terror] when you open the new document and begin to formulate that first sentence? Or derive the same small comfort from putting the title at the top of the page, formatting it nicely, and saving the (as yet still blank) document to file? Why is it that I can only write 1,000 words a day, whether I have finished them by 11am, or 9pm, and does everyone have a ‘natural’ daily word limit? Is there an optimum number of jokey asides to include in a paper? And how do you turn off autocorrect in the latest version of Word?

With all that in mind, I thought I would be therapeutic to briefly summarise the main stages that I pass through when I am writing.

The dreaded introduction.

Undoubtedly my least  favourite part of writing. The uncertainty, the weight of expectation, the fear that you have forgotten how to do it. The enormously intimidating existing scholarship and the huge pile of primary material. The plan that made sense when you wrote it but which is now an undecipherable mass of crossed out paragraphs, arrows pointing to nowhere, and an obscene number of question marks. NB. This entire post could have been written just about this point.

favourite part of writing. The uncertainty, the weight of expectation, the fear that you have forgotten how to do it. The enormously intimidating existing scholarship and the huge pile of primary material. The plan that made sense when you wrote it but which is now an undecipherable mass of crossed out paragraphs, arrows pointing to nowhere, and an obscene number of question marks. NB. This entire post could have been written just about this point.

The false start.

Continuing the theme, the false start. You finally start getting something down, you pick your way through a particularly difficult bit of historiography, and you are feeling quite pleased with yourself. You stop for a cup of tea, and when you return, realise that you have 2,000 words of a 4,000 word paper, but you haven’t even mentioned the topic in the title yet. None of your 2,000 words are essential and most will need to be cut so you can actually address some of the important things. But the great news is: a false start is infinitely better than no start, and you can just deal with the editing later. NB. Save the original file because you might be able to use it somewhere else.

The comforting middle bit.

Before this post descends into paralysing misery, I usually find that once I get going, I tend to get into a groove and progress reasonably steadily. I generally target either a certain number of words each day (c. 1,000) or completion of a particular section from my plan. Attacking longer pieces of writing in bite sized chunks is essential and helps to make me feel accomplished every day, not just at the last. That said, there will inevitably be…

![Possibly blasphemously, I also fondly think of the darkest day as the Slough of Despond [William Blake, Frick Collection New York].](https://manyheadedmonster.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/william_blake_-_john_bunyan_-_cristian_reading_in_his_book_-_frick_collection_new_york.jpg?w=221&h=300)

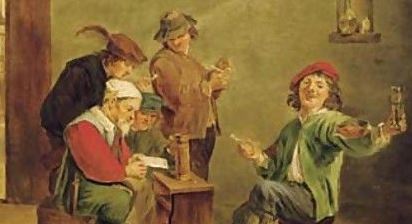

Possibly blasphemously, I also fondly think of the darkest day as the Slough of Despond [William Blake, Frick Collection New York].

There are lots of reasons for the darkest day, that day when your muse deserts you, and writing simply does not happen, or progress is so slow that an outsider wouldn’t notice it. For me it is usually when I am tackling a bit that is tricky conceptually, or if I am trying to synthesise and reduce something rather complicated into a manageable and not too distracting size. After hours of furrowing my brows, picking up and putting down books, groaning, re-reading articles, chewing my fingernails, cutting, pasting, and standing up to look out of the window, I usually have something useable. That’s the moment I save those precious 300 words, put my whip down, and leave that dead horse alone.

The race for the finish.

Finally, your steed has miraculously revived, the wind is in your hair, and you are heading into the final straight! Everything is great. You have crossed out the majority of your plan, you have discarded all the boring and inessential parts, you have mastered that horrible bit about predestination. You are so excited about finishing you write two sections in one day. Your conclusion is so close you can smell it. Your examples are fitter, your jokey asides are funnier, your analogies more similar, and your argument more persuad-ier. It turns out that dreaded introduction was worth it after all. Now – to the pub*!

*It is important to celebrate your accomplishments, but please drink responsibly.

![Possibly blasphemously, I also fondly think of the darkest day as the Slough of Despond [William Blake, Frick Collection New York].](https://manyheadedmonster.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/william_blake_-_john_bunyan_-_cristian_reading_in_his_book_-_frick_collection_new_york.jpg?w=221&h=300)