Our latest post in the Postgraduate and Early Career Takeover is from Joe Saunders. Joe has just started a PhD at the University of York using wills to study the social networks of the print trade in England c.1557-1666. Find Joe on twitter at @joe_saunders1.

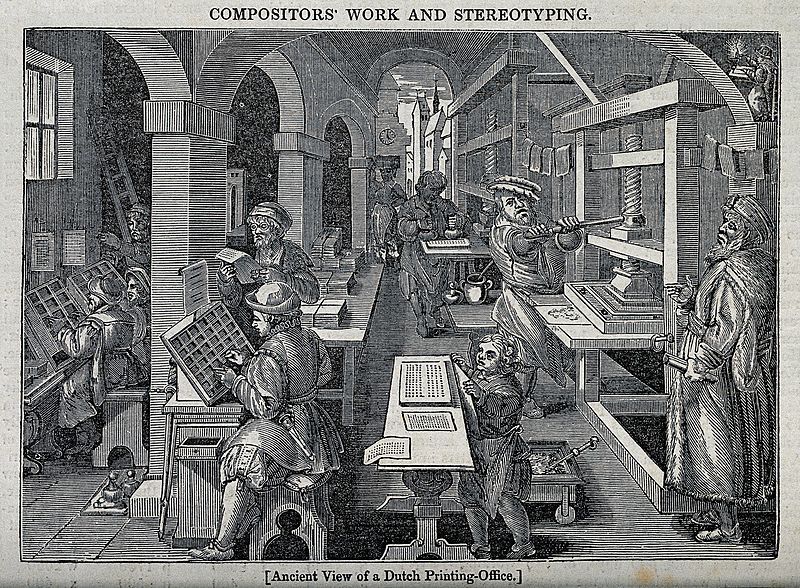

We are this year ‘working from home’; struggling with work-life balance; and have ‘Key Workers’ in our supermarkets, hospitals and care-homes. What constitutes important labour is a contemporary debate but also interests historians who seek to define and locate work. Histories of literature are a case-in-point, with focus oscillating between the labour of authors, readers and publishers. In recent decades we have come to know a great deal about text creation and circulation during the hand-press era with work on the producers and movers of texts; publishers, printers and booksellers as they turned an author’s ideas into something tangible and passed them to an audience. The transfer from the author’s mind to printed page and then to the reader required a significant amount of labour from a variety of actors in a myriad of roles from financing a text through to those who carried the finished products along country roads.

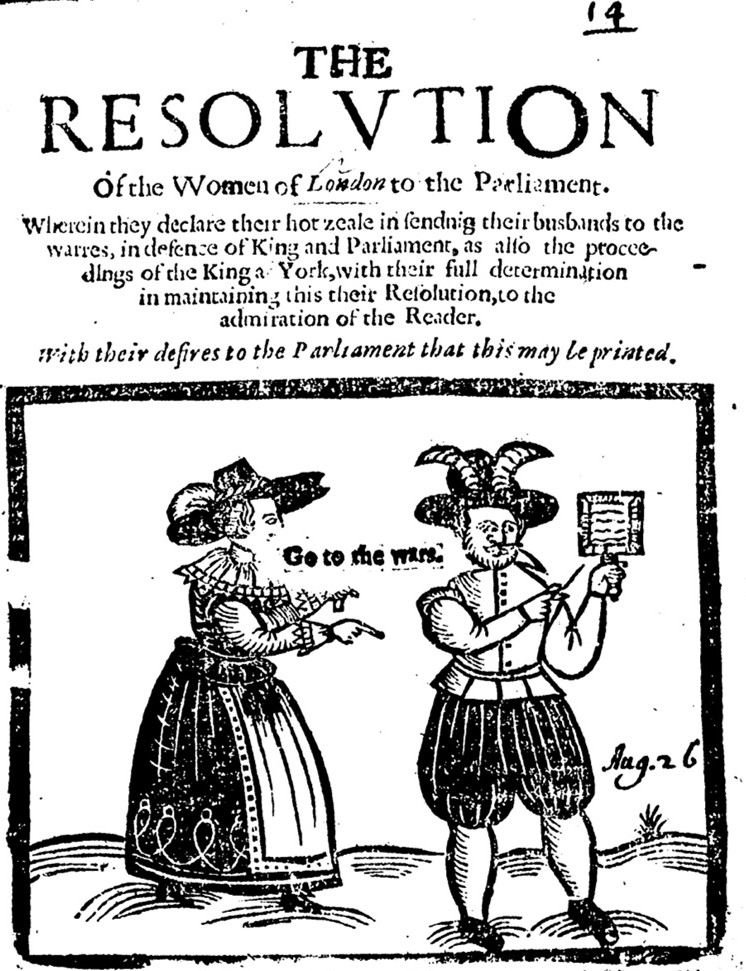

Bertolt Brecht in his 1935 poem ‘A Worker Reads History’ imagined how the workers who built the great monuments of the world figured into histories dominated by great men. He asked ‘but was it kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone?’. Of course, the answer is no, but their names adorn these structures nonetheless. Though the process of text creation and movement in early modern England was gendered, classed and regionalised research has necessarily focused on the better offs who left their names on imprints and records of the Company of Stationers; the livery company which held a theoretical control over the membership and products of the print trade. This is the case across the History of the Book where source survival means most work on reading and authorship is also done on the middling sorts and elites.

The 2020 publication Women’s Labour and the History of the Book in Early Modern England brought together a range of essays dealing with reading, authorship and production. The focus was more towards countesses than chapmen-or-women but an exception was Craig’s essay on the rag-women who collected material for papermakers. This research recovered the labour of people who were critical to the production of texts but are largely absent from the records and therefore from our understanding. It was argued implicitly that to look for the lowest sort of women in the trade is the first step to finding them.

Continue reading