Brodie Waddell

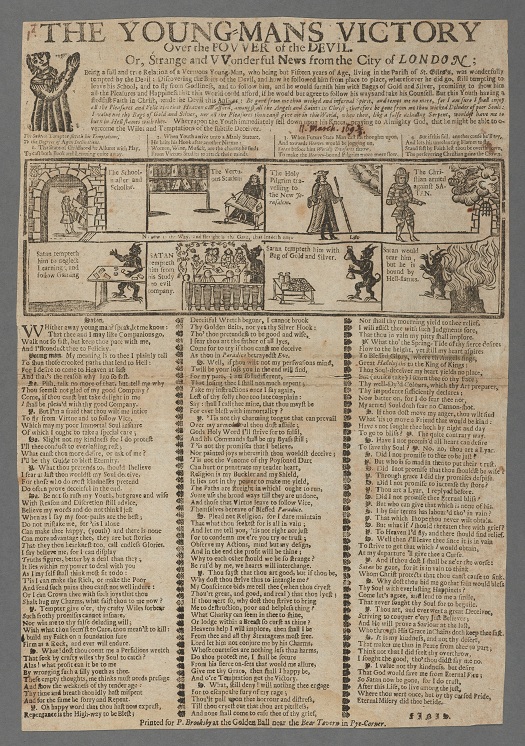

Several months ago, inspired by a post by Gavin Robinson, I shared an image of a broadsheet called The Young-Mans Victory Over the Povver of the Devil that seemed to fit the definition of a comic strip. That one, dating from the 1690s, was the earliest I had found at the time and it remains my favourite of the genre, but I’ve since come across an earlier contender.

I discovered it on a wonderful blog called The 1640s Picturebook where Ian Dicker has posted dozens of images from the period along with detailed analysis of the costumes depicted. In June of last year, they posted an image of The Malignants Trecherous and Bloody Plot (1643), which depicted a plan apparently launched by the MP, Edmund Waller, bring an end to the first of the English Civil Wars. According to the confession of one of the plotters quoted in the ODNB, it began peaceably enough:

‘It came from Mr. Waller under this notion, that if we could make a moderate party here in London, to stand betwixt the gappe, and in the gappe, to unite the King and the Parliament, it would be a very acceptable work, for now the three Kingdomes lay a bleeding, and unlesse that were done there was no hopes to unite them.’

But the peace plan quickly turned to war: in its final form, the plot apparently called for an armed rising and seizure of the key points of the City in order to let the king’s army in.

The plot ended before it had begun when the plotters were betrayed and arrested. Somehow, seemingly through a mixture of powerful rhetoric and shameless bribery, Waller managed to escape the grisly punishment inflicted on some of his co-conspirators and was permitted to go into exile after only a year and a half in prison.

The Malignants Trecherous and Bloody Plot (1643) via The 1640s Picturebook.

The upshot of all this was a detailed broadsheet published in August of 1643. It has twelve panels, each of which includes a running narration of the events as they unfolded, from the hatching of the conspiracy to the execution of some of the offenders.

‘Come let us joyne our selves to the Lord in an everlasting Covenant which shall not be forgotten’, citing Jeremiah 50:5.

It even included some text in a speech bubble, said to be a key part of a ‘true’ comic strip – though as befits a seventeenth-century comic it is a quotation from scripture rather than a supervillain’s monologue.

So have we pushed the date of the first comic strip back still further? Or is this too much of a stretch?