[In our mini-series ‘A Page in the Life’, each post briefly introduces a new writer and a page from their manuscript. In this post, Brodie Waddell explores the wider implications of a rather clumsy poem about the cloth industry written by a seventeenth-century tradesman.]

The Essex town of Coggeshall was not known for literary genius. It inspired no Hamlet nor Paradise Lost nor even a Pilgrim’s Progress. Its only published authors were two clergymen who spent a few years there in the 1640s.

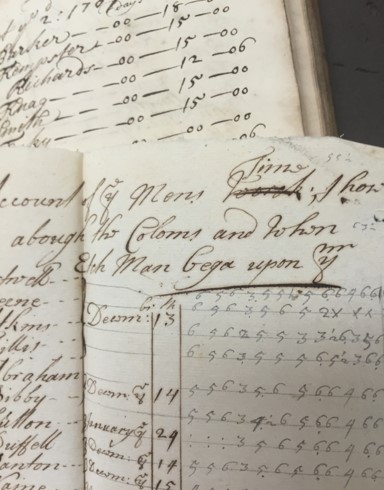

However, in the late seventeenth century, it was home to a tradesman named Joseph Bufton, who filled up notebook after notebook with a diverse array of writings. He devoted a great many pages to chronicling his local community and the state of the nation as a whole, a practice which I discussed in an earlier post.

But he also filled many volumes with other sorts of writing, including devotional texts, financial accounts and even a bit of poetry. I’ve just published a new article in the Journal of Social History that looks at what Bufton and others like him can tell us about literacy, work and social identity in early modern England, so I thought I would mark the occasion by offering another page from his notebooks that illuminates some of these themes. Continue reading

I’m reading the chapter in my 1982 edition of Alice Clark (the only history book I stole from my mother’s bookshelves), complete with a woodcut of a woman haymaking on the cover (although this image has been edited to remove the couple canoodling in the background which is present in the original below). Is this deeply significant? Probably not …

I’m reading the chapter in my 1982 edition of Alice Clark (the only history book I stole from my mother’s bookshelves), complete with a woodcut of a woman haymaking on the cover (although this image has been edited to remove the couple canoodling in the background which is present in the original below). Is this deeply significant? Probably not … Those who have never read Alice Clark’s Working Life of Women might wonder why we would pay any attention to a work that is a hundred years old, and superseded by recent research on women. Yet anyone who works on the history of women, and particularly the history of women’s work, in early modern England owes a debt to Alice Clark’s work. It was reissued in 1982 with an introduction by Miranda Chaytor and Jane Lewis, and again in 1992 with an introduction by Amy Erickson. As Natalie Davis noted in a paper delivered at the Second Berkshire Conference in 1974, Clark consulted archives, differentiated among women, and had an overarching theory.

Those who have never read Alice Clark’s Working Life of Women might wonder why we would pay any attention to a work that is a hundred years old, and superseded by recent research on women. Yet anyone who works on the history of women, and particularly the history of women’s work, in early modern England owes a debt to Alice Clark’s work. It was reissued in 1982 with an introduction by Miranda Chaytor and Jane Lewis, and again in 1992 with an introduction by Amy Erickson. As Natalie Davis noted in a paper delivered at the Second Berkshire Conference in 1974, Clark consulted archives, differentiated among women, and had an overarching theory. At first glance Alice Clark seems the most unlikely of historians. Due to ill health she managed only sporadic periods at school and she never went to university. She was a capitalist, not a scholar, spending most of her adult life as a director of the family business, known today as Clarks Shoes Ltd. Yet from a young age she was a voracious reader and would have joined her sister at Cambridge had her parents not felt strongly that the shoe company would benefit from the involvement of a female family member.

At first glance Alice Clark seems the most unlikely of historians. Due to ill health she managed only sporadic periods at school and she never went to university. She was a capitalist, not a scholar, spending most of her adult life as a director of the family business, known today as Clarks Shoes Ltd. Yet from a young age she was a voracious reader and would have joined her sister at Cambridge had her parents not felt strongly that the shoe company would benefit from the involvement of a female family member. The centenary of the publication of this seminal work presents a great opportunity to both celebrate the scholarship of Alice Clark, and to reflect on the current state of the history of early modern women’s work. And so, we would like to invite you, dear reader, to join an online reading group here on the many-headed monster that will do just that.

The centenary of the publication of this seminal work presents a great opportunity to both celebrate the scholarship of Alice Clark, and to reflect on the current state of the history of early modern women’s work. And so, we would like to invite you, dear reader, to join an online reading group here on the many-headed monster that will do just that.