This post is part of the Monster Carnival 2022 – Why Early Modern History Matters Now. Christophe Schellekens (@Christophe_Fir) works as a non-permanent lecturer in social and economic history at Utrecht University (The Netherlands). His main research interest is the history of commerce and capitalism in the pre-modern period.

Christophe Schellekens

“How are your dead Florentine merchants doing today?” A friend and fellow PhD-researcher regularly asked me that question when we ran into each other in the corridors of the European University Institute. In that institution, where we both did our doctorate between 2013 and 2018, a small but vibrant group of early modern historians (at the time five faculty members) was often confronted with such questions about their topic from colleagues working in other disciplines.

Why did my doctoral research on (absolutely certainly physically very dead) Florentine merchants in sixteenth century Antwerp matter to my friend, who studies EU administrative law? What did I have to share with my EUI flat mate researching contemporary welfare state regimes, or with one of the many other colleagues at the institute who were tackling topics that are more readily considered as socially or policy relevant? How dead or alive is the early modern world that I study?

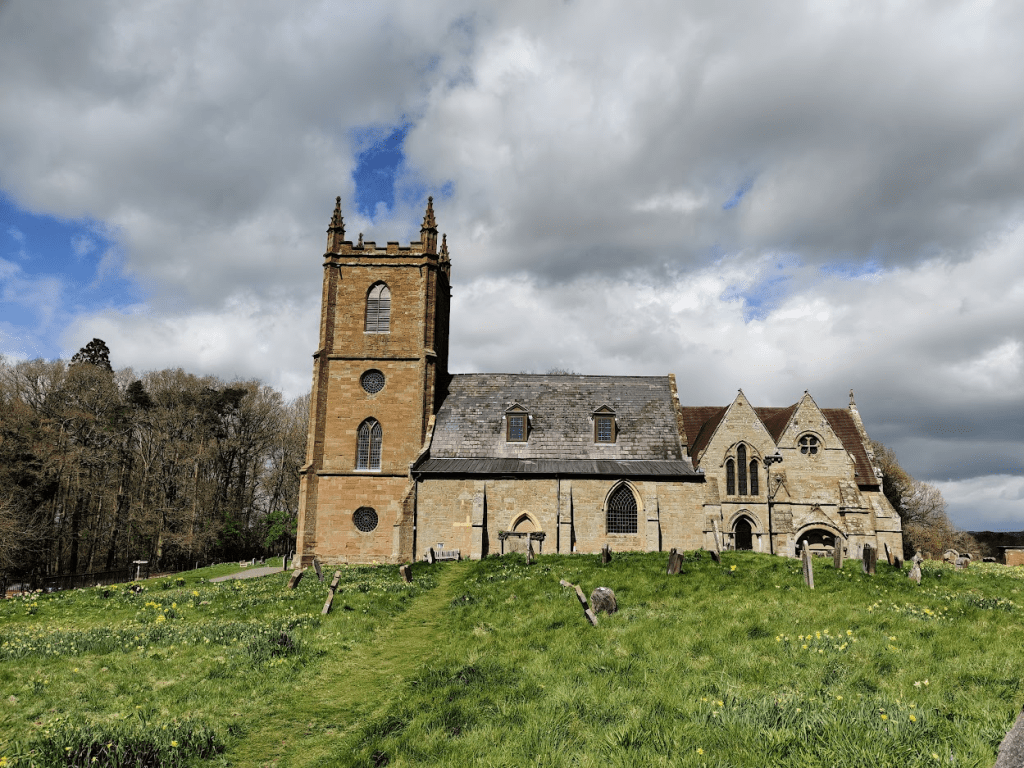

The EUI’s Villa Salviati, a Renaissance building where lawyers inquire about the dead subjects of historians. Photo by Sailko on wikimedia.

The question how early modern history matters can be approached from a variety of angles and experiences. As I later worked as a postdoc in a EU Horizon 2020 project with a strong focus on societal impact, and then started to work as a lecturer in a PPE-program, my take on it is strongly shaped by working over the past decade as an early modernist in environments where early modern history is not at the institutional and intellectual core of the agenda of my direct workplace. In that sense it is thus a take from the margin. Continue reading