Jonathan Willis

Tag Archives: the craft

Marooned On An Island Monographs: An Early Modern Social History Summer Reading List

Mark Hailwood

Memorial and history, Part 5: in which history delivers a warning from history, and I talk about ‘feelings’

Laura Sangha

This is a final post in a short series relating to Exeter’s martyrs memorial, the others are on the following:

- The story of the two martyrs commemorated on the memorial, Thomas Benet and Agnes Prest.

- Our main source of information about Tudor martyrs, John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments, and it’s own role as a memorial to the past.

- Other English examples of monuments to martyrs and when and why they were erected.

- The remarkable Harry Hems, designer of Exeter’s monument and an important collector of historical artefacts in his own right.

In this final post I conclude with some thoughts on the ways that objects and places are invested with meaning, and the relationship between space, memory and history.

My final question about Exeter’s martyr memorial was: what is ‘Livery Dole’? The plaque on the monument stated that Thomas Benet had suffered at ‘Livery Dole’ but although I knew what an aircraft livery was, or could countenance a livery stable, otherwise I was drawing a blank. Exeter Memories came to my rescue again: Livery Dole is an ancient triangular site between what is now Heavitree Road and Magdalen Road. It was used as a place for executions – the last took place in 1818, when the unfortunate Samuel Holmyard was hanged for passing a forged City Bank one pound note.

Liverydole now made sense – it meant that the Exeter memorial had therefore been erected near to the spot where Thomas Benet had been burnt to death. Hence my final post is about the meanings and significance that are attached to particular places and features of the landscape. All of the Protestant monuments that I have uncovered are erected as close as possible to the original site of the martyrdom, they are a deliberate attempt to attach particular memories to those sites, for later generations to read. Nearby, Heavitree’s almshouses represent a similar attempt to shape historical memory – they were erected in 1591 by Sir Robert Dennis, by tradition in penance for the part his ancestor had played in the execution of Thomas Benet in 1531. The ancestor in question was Sir Thomas Dennis, who had been the Sheriff of Exeter at the time and who had sentenced Benet to death. This act of charity proved that the current Sir Dennis was now firmly on the side of the true Church, unlike his unenlightened Catholic ancestor. Continue reading

Memorial and history, Part 3: in which Mary Beard sits on a bench

Laura Sangha

This is the third in a series of posts relating to Exeter’s martyr memorial. The first post, contains the details of the martyrs themselves, the second, is on John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments.

What I really wanted to know about Exeter’s martyr monument, was who paid for and created it – when was it erected, how and why? A third plaque on the memorial yielded some information:

To the glory of God & in honour of his faithful witnesses who near this spot yielded their bodies to be burned for love to Christ and in vindication of the principles of the Protestant Reformation this monument was erected by public subscription AD 1909. They being dead yet speak.

Thus the obelisk dates from the twentieth-century, which makes sense – the English Reformation was profoundly iconoclastic and it is hard to imagine money being spent on erecting monuments in an age when destruction of imagery was a mark of Protestant identity. In fact the image of Agnes Prest from the 1887 edition of Foxe that I mentioned  in my previous post supports just this point. It depicts a visit that Prest paid to Exeter Cathedral, where she met a ‘cunning’ Dutch craftsmen who was apparently repairing the images and sculptures that had been disfigured during the previous, iconoclastic reign of Edward VI. Prest supposedly said to the Dutchman ‘what a mad man art thou… to make them new noses, which within a few dayes shall all lose their heades’. In response to this rather prophetic prediction of further reform, the stonemason replied with a well thought out theological argument: ‘Thou art a whore!’. Quick as a flash, Prest replied ‘Nay, thy Images are whores, and thou art a whore hunter: for doth not God say you goe a whoring after straunge Gods, figures of your owne making?’ Continue reading

in my previous post supports just this point. It depicts a visit that Prest paid to Exeter Cathedral, where she met a ‘cunning’ Dutch craftsmen who was apparently repairing the images and sculptures that had been disfigured during the previous, iconoclastic reign of Edward VI. Prest supposedly said to the Dutchman ‘what a mad man art thou… to make them new noses, which within a few dayes shall all lose their heades’. In response to this rather prophetic prediction of further reform, the stonemason replied with a well thought out theological argument: ‘Thou art a whore!’. Quick as a flash, Prest replied ‘Nay, thy Images are whores, and thou art a whore hunter: for doth not God say you goe a whoring after straunge Gods, figures of your owne making?’ Continue reading

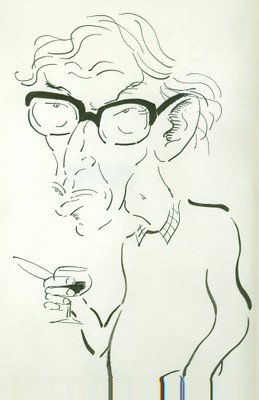

Early modern history after Hobsbawm

Brodie Waddell

Eric Hobsbawm was not an early modernist. Although he wandered into the seventeenth century every once and awhile, his scholarship was focused on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yet it would be unjust to dismiss him as irrelevant. Not only did he come up with some of the key concepts used by early modernists – such as ‘primitive rebels’, ‘invented traditions’ and even ‘the general crisis of the seventeenth century’ – he also very publically wrestled with the problem of politically informed and socially committed history.

Two weeks ago, a truly extraordinary gathering of historians met to explore these issues at the ‘History After Hobsbawm’ conference in London. I don’t exaggerate when I say this was a remarkable group – Sam Wetherell suggested the line-up was ‘like the Glastonbury of modern British history’, which seems about right. The result was a lot of great conversations at the event, online and of course at the pub afterwards. There are a bunch of reports, reviews, podcasts and tweets collected at the conference website.

I wanted to draw attention to a few of those pieces written by early modernists that may be of interest to our readers. If you have any comments or questions I’d encourage you to put them here as there are no comments on the conference blog. I’ll pass comments here on to the authors.

The ‘spectres of Marx’ that haunted many of the conference conservations were very visible in the commentaries from early modernists. Hillary Taylor discussed how Jane Whittle, Andy Wood and Lucy Robinson dealt with issues such as ‘class’ before the industrial revolution and ‘primitive rebels’ outside of formally organised protests. She suggested that some ‘ecumenical sampling’ of Marxist analysis – by both Marx himself as well as less well-known thinkers like Ferruccio Rossi-Landi and Nicos Poulantzas – can still illuminate key aspects of early modern society. Mark Hailwood agreed and suggested that the label ‘post-Marxist’ might be appropriate as such an approach is neither anti-Marxist nor even strictly non-Marxist, but instead ‘picking up some of the pieces’ left behind after the ‘purgatory of the 1990s’. Indeed, he noted that many so-called Marxists – including Hobsbawm – have been doing this all along. Dave Hitchcock looked specifically at Gareth Stedman Jones’s discussion of the supposed ‘paradox’ of ‘good Marxist history’. Jones seemed to claim that Marx was merely a distraction from the strength of the longer tradition of intellectual critique that preceded him. Dave, in contrast, argued strongly that without Marx and successors like Hobsbawm historians would have a much weaker awareness of the history of social experience and of the brutal realities of material existence.

The second major theme to emerge from these discussions was the link between past and present in historical scholarship. This was perhaps most prominent in Lucy Robinson’s talk, summarised by Hillary, as it focused on the ‘history’ of the 2010 Brighton school students protest, in which the ‘historian’ was amongst the crowd! However, it is also very relevant to early modernists. Hillary, Mark and Dave all noted the power of ‘socially committed’ scholars in bringing to light previously neglected topics such as protest and subordination. Moreover, the crushing defeats of organised labour and international communism in the 1980s clearly had an effect on how historians used concepts like ‘class’: the shifting political climate directly influenced academic debates and methodologies. The panellists discussed by Robert Stearn made this very clear in their analysis of the retreat of traditional ‘labour history’ over the last generation. Here, the impact of a changing political situation are plain to see. This final point was driven home for me in the panel I wrote about, in which John Elliot, Geoffrey Parker and Sanjay Subrahmanyham talked about ‘the seventeen-century crisis’. It is not difficult to find some of the momentous events of the twentieth century – namely the Depression, the World Wars, the rise of globalisation and the discovery of climate change – shaping the way scholars conceived of early modern society. It’s often said that we can’t escape the past, but it’s clear that even historians can’t escape the present either.

- Mark Hailwood, ‘In Search of Post-Marxism’

- David Hitchcock, ‘Gareth Stedman Jones on Marxism’

- Hillary Taylor, ‘Marxist and Post-Marxist Social History: Lucy Robinson, Jane Whittle and Andy Wood’

- Robert Stearn, ‘What happened to class? Sean Brady, Sonya Rose, Marjorie Levine-Clark’

- Brodie Waddell, ‘The Seventeenth-Century Crisis: John Elliott, Geoffrey Parker and Sanjay Subrahmanyam’

There are also some earlier thoughts on Hobsbawm from me and (in the comments) Mark, Jonathan, Laura and Newton Key, that might be relevant.

Grave-robbing and heritage: the problem of conserving the past – Part 2

Laura Sangha

In the first post of this heritage double-header, I discussed my recent visit to Sir John Soane’s Museum – a trip that raised a number of questions about the best way to preserve the past, and the difficulties of doing so. Here I continue the theme by drawing out some key areas and offering some possible solutions:

Open access to the past – no doubt we would like all archives and historical artefacts to be freely available to the public, but that is hardly practicable. In reality open access damages the relics of the past and shortens their life span.

Do the Soane’s museum’s limited walkways validate limited access?

Limited access to the past – do some people have more right to see collections than others? Do those who help fund preservation, or whose interest goes beyond mere curiosity (the benefactor, the architecture student, the historian) have a better claim? How can that be squared with public funding of heritage or with sites with particular national, international or global importance?

Resources – conservation is an expensive business, and rightly is not at the top of a government’s budgetary plans. One way to raise funds is to attract visitors who will spend money in the gift shop, on the guide book, or on a tour. Some collections wouldn’t survive without this income, but attracting large visitor numbers brings further preservation problems.

Meaning of preservation – surely the crux of the heritage questions lies here – why do we want to keep this stuff anyway? The past can help us to understand ourselves as a society or nation, but only if people actually encounter it. Perhaps we should limit access to a few chosen experts, whose remit is to tell other people about it? But isn’t that unfair? And who gets to choose who the experts are and polices their outputs?

Process of preservation – How do we decide what is worth protecting, especially given that historical tastes shift so dramatically over time? Something that one generation values might be seen as rubbish by the next. During the dissolution of the monasteries, manuscripts that we would consider to be priceless were used to wipe boots and wrap food in, highlighting the tendency for ritual and deliberate destruction of the past for political or propaganda purposes. What universal priorities might there be to identify what is important and to provide rules for preservation?

Means of preservation – a recent trend is for historically important buildings to be adapted in order to preserve them. Old meeting houses and chapels that have fallen into disuse are renovated to create characterful homes or blocks of apartments. Abandoned warehouses become nightclubs, archaic power stations art galleries. On my street in Exeter, the old electricity building has become a climbing centre – inside photographs show the interior as it used to be, and original features such as the floor to ceiling tiling can now be seen by anyone that wanders in (you don’t have to pay or climb!). Across the river the splendid seventeenth-century Custom House is now a shop, complete with original plasterwork, wood paneled walls and a sweeping staircase – again, when the shop is open then the public can explore to their heart’s content.

Making the past benefit the present – changing the purpose of a building is of course a compromise – it will alter the contours and function of the original, and in the case of a conversion to private dwellings, only preserves the exterior for the benefit of the public. But I have to admit to being rather sympathetic to this. Evidently we do not have the means to secure every historical monument that we would like to, and a change of purpose does give buildings a more secure future, albeit an altered one. But this is not simply pragmatic – I also think that if the social function of a building has become redundant, then it is a virtue to open the space up to a new constituency by making it useful and appealing to them. The ‘Wetherspoons’ pub chain has a strong track record here. In Exeter it has two pubs in historic repurposed buildings: George’s Meeting House with its cavernous, airy interior, splendid stained glass, twin galleries and pews, is a particular delight (even with the gaming machines that now obscure the magnificent pulpit).

Meanwhile the ‘Imperial’ has gone through many transformations recently: originally a nineteenth-century grand private dwelling, it became a hotel in the 1920s before being bought by the chain in the 1980s. None of this has reduced the visual impact of the magnificent orangery.

And ultimately I am left wondering – what is the purpose of preserving something for as long as humanly possible, to the exclusion of everything else? Surely the stuff of the past is only useful if we actually benefit from it? Intrinsically it is all just bits of stone, wood and paper, lumpish and meaningless until a human actively engages with and imparts meaning to it. Isn’t it preferable that millions of people get to see Pompeii before the inevitable happens and it dissolves back into the dust, rather than pointlessly extending its life whilst nobody is allowed near it?

And ultimately I am left wondering – what is the purpose of preserving something for as long as humanly possible, to the exclusion of everything else? Surely the stuff of the past is only useful if we actually benefit from it? Intrinsically it is all just bits of stone, wood and paper, lumpish and meaningless until a human actively engages with and imparts meaning to it. Isn’t it preferable that millions of people get to see Pompeii before the inevitable happens and it dissolves back into the dust, rather than pointlessly extending its life whilst nobody is allowed near it?

Thus perhaps sensitive compromise is the order of the day. To return to the Sir John Soane’s Museum, given the chance, there were things that I would have liked to discuss further with my volunteer. Currently the museum does limit the number of people allowed into the museum at any one time, but other measures might alleviate overcrowding. Could a one-way system be introduced to allow visitors to navigate the house? Maybe this could be co-ordinated with the times of guided (paid) tours to prevent blockages in the narrow walkways. For smaller heritage sites (often those most in need of cash) perhaps we should reconsider the principle that all museums are free – currently collections that are funded directly by the central government are all free to view. Yet charging admittance to some places could raise revenue and redirect the more casual tourist away to larger, better equipped, free attractions. My first post provoked lots of response from archivists and historians on twitter and this issue was raised by several people. Probably better than paid entrance is Manya Zuba’s suggestion that free viewings should be by appointment, with slots available throughout the day (short term exhibitions at various museums and galleries, including the British Museum, already use a booking system like this). As Sjoerd Levelt pointed out, this would add a threshold, ‘but one that can be ameliorated by some proper thinking about well-aimed inclusive policies’. Access would therefore be open to all, if they were sufficiently interested to plan ahead and spend the time making an appointment.

Finally, Soane’s museum also currently houses the original series of paintings for William Hogarth’s ‘A Rake’s Progress’, although you can only view them briefly if the attendant is on hand to open up panels to reveal them. My guess would be that the paintings are important in drawing visitors to the museum – perhaps they might be better placed somewhere where greater numbers of people could see them to better advantage. Maybe more, and more friendly information should be given to visitors to explain the current arrangements and to encourage visitors to be especially careful when navigating around the museum.

Detail from painting four of The Rake’s Progress – ‘A Rake Arrested, going to court’. The incredible detail in William Hogarth’s paintings richly rewards sustained examination, but there is little opportunity for this currently.

But these are just the musings of an amateur who knows very little about this complex issue. There aren’t any simple answers as to how we should conserve our national heritage, and at every stage the interests of different groups must be carefully balanced and weighed. And of course I wouldn’t really steal a finger out of a grave, however long-dead and important it’s owner was.

Grave-robbing and heritage: the problem of conserving the past – Part 1

Laura Sangha

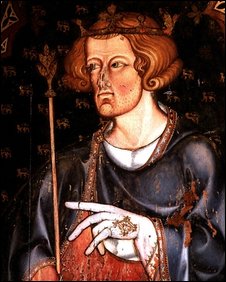

When the tomb of Edward I was opened in Westminster Abbey in 1771, the renowned antiquarian Richard Gough allegedly reached into the gaping coffin and snagged himself a little royal memento. The incident was recorded by William Cole, and it is recounted by Rosemary Sweet in her Antiquaries: The Discovery of the Past in Eighteenth-Century Britain (p. 278):

Mr G was observed to put his Hand into the Coffin and immediately apply it to his Pocket: but not so dexterously that the Dean of Westminster saw it: he remonstrated against the Proprietary of it, and Mr G denying the Fact, the Dean insisted on the Pocket being searched: when they found that he had taken a Finger; which was replaced.

In Gough’s defence, I should add the proviso that Cole was not sure whether to believe the story or not. But let’s assume the story is true and that Gough had attempted to make off with a macabre souvenir of this momentous occasion. At first it seems shocking that a well-respected antiquarian, someone dedicated to uncovering and preserving the nation’s past, might act in such a selfish and self-centred way. But the more you think about it, the less surprising it is. Put yourself in Gough’s shoes – wouldn’t you be tempted to take a piece of the nation’s glorious history for your own? Or would your sense of ‘proprietary’ and your respect for the dead stay your hand? What harm would it do to lift one of those smaller bones, wouldn’t there still be plenty left? You would look after it and treasure that little finger, and get great pleasure from possessing it, wouldn’t you?

Beyond this particular dilemma the reality is that conserving the documents and objects of the past is a cultural, technical, economic, intellectual and moral minefield. Wherever you turn conservation is fraught with ideals in tension and competing interests, and each contributor to the argument has perfectly reasonable logic to support their point of view. Tricky questions abound: who owns the relics of the past, and who should be given access to them? How to you balance preservation with exhibition? What’s the point of conserving anything, and how do you decide which bits should be kept? Preservation or restoration? Open access or aggressive protectionism?

We have all heard stories of archivists who are so intent on protecting their collection that they become more a hindrance than a help in attempting to access the stuff of the past. Yet at the same time we can sympathise with the impulse to protect and extend the life of the fragile documents that are so crucial to being able to understand our history – it’s just that, if no one gets to see them, how can those histories be written? It’s not only paper that needs to be protected either. For many years now, worrying stories about the disintegration of the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, a UNESCO world heritage site, have littered the news, with the site becoming a symbol for what some see as decades of mismanagement of Italy’s cultural sites. Pompeii is fundamental to our understanding of everyday life in ancient Rome, and it receives about 2.5 million visitors each year. It isn’t hard to make a case for its international significance and value, but it does seem that it is very hard to effectively conserve it.

We have all heard stories of archivists who are so intent on protecting their collection that they become more a hindrance than a help in attempting to access the stuff of the past. Yet at the same time we can sympathise with the impulse to protect and extend the life of the fragile documents that are so crucial to being able to understand our history – it’s just that, if no one gets to see them, how can those histories be written? It’s not only paper that needs to be protected either. For many years now, worrying stories about the disintegration of the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, a UNESCO world heritage site, have littered the news, with the site becoming a symbol for what some see as decades of mismanagement of Italy’s cultural sites. Pompeii is fundamental to our understanding of everyday life in ancient Rome, and it receives about 2.5 million visitors each year. It isn’t hard to make a case for its international significance and value, but it does seem that it is very hard to effectively conserve it.

For me, it was a recent visit to Sir John Soane’s museum in London’s Lincoln’s Inn Fields that brought the issues into sharp focus. It’s a fascinating place – Soane was a Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy and a great collector, with a houseful of books, casts and models. In 1833 he negotiated an Act of Parliament to settle and preserve the house and collection for the benefit of ‘amateurs and students’ in architecture, painting and sculpture, on the condition that the interiors be kept as they were at the time of his death. In the nineteenth century some alterations were made to the house however, and a five-year restoration programme to restore the museum is just reaching its final stages.

Today this little museum is enormously popular. It is on the tourist trail and appears on the Lonely Planet’s list of best museums and galleries in London. Indeed, it is a wonderful place, and was of particular interest to me, given that my current research is on Ralph Thoresby, another chap whose house also doubled up as a museum. However, Soane’s museum was very busy and overcrowded, and it wasn’t easy to negotiate around the narrow walkways and tight corners whilst also keeping well away from the innumerable artefacts that clogged every available surface. Whilst waiting to go into one room, we had an illuminating discussion with the volunteer who was guarding the door. Having started with a pleasantry that it was rather busy, the volunteer curtly told us that the popularity of the museum was a disaster. We wondered why that was – surely high visitor numbers helped to secure the museums future? Not so – it is free to enter the museum, so large numbers of visitors bought more trouble and damage than they were worth. The volunteer went on to state that it was ridiculous that the site had become a tourist attraction, and that he believed the museum should be returned to its original function – as a library and resource for architectural students only.

This brief exchange left me with lots of questions. Instinctively, as a professional historian, I felt that I was a more worthy visitor that the gaggling mass of rather uncomprehending tourists who zoomed round the museum before consulting their guidebooks to check out the next stop on the museum trail. But according to the volunteer, I had as little right to view the museum as them, and admittedly it is true that seeing the museum was hardly vital to my research. I do pay taxes in the UK though, and given that a large part of the museum’s funding comes from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, surely I was a stakeholder in the museum? And what about the trustees’ responsibility to ensure that the collection is accessible to the general public? Soane’s museum is therefore an excellent window into the heritage problem, which I will be exploring further in my second post on this topic next week.

This brief exchange left me with lots of questions. Instinctively, as a professional historian, I felt that I was a more worthy visitor that the gaggling mass of rather uncomprehending tourists who zoomed round the museum before consulting their guidebooks to check out the next stop on the museum trail. But according to the volunteer, I had as little right to view the museum as them, and admittedly it is true that seeing the museum was hardly vital to my research. I do pay taxes in the UK though, and given that a large part of the museum’s funding comes from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, surely I was a stakeholder in the museum? And what about the trustees’ responsibility to ensure that the collection is accessible to the general public? Soane’s museum is therefore an excellent window into the heritage problem, which I will be exploring further in my second post on this topic next week.

The many stages of writing: a personal take

Laura Sangha

For the past few years, I have been asked to contribute to a postgraduate training session on ‘Preparing to write’ which I deliver jointly with a professor in the English department. It is something that I really enjoy doing, because it is a chance to compare my own experiences and practice with other researchers. And each year I am struck anew by the similarities in the way that we approach our research, as well the fact that there are always new techniques and ways of working out there that I haven’t considered. Whilst the English professor has a complicated system of index cards and quotations, I tend towards colour-coded excel spreadsheets, both of which methods have something in common with Keith Thomas’ labour (and envelop) intensive working practices. The informal and inclusive nature of the discussion of the training sessions are a great way to encourage reflection on our working practice, many of which seem to organically emerge and ossify throughout our training and early career.

Alongside thinking about preparing for writing, I have just bashed out my first paper on my new research into Ralph Thoresby, and found this blog post on what we might mean by ‘pace’ in writing incredibly useful for thinking about the processes involved. Recently Matt Houlbrook’s lyrical photo essay/ biography of a book chapter had also set me wondering just how similar our experiences are when it comes to writing. Does everyone feel the same deep unease [terror] when you open the new document and begin to formulate that first sentence? Or derive the same small comfort from putting the title at the top of the page, formatting it nicely, and saving the (as yet still blank) document to file? Why is it that I can only write 1,000 words a day, whether I have finished them by 11am, or 9pm, and does everyone have a ‘natural’ daily word limit? Is there an optimum number of jokey asides to include in a paper? And how do you turn off autocorrect in the latest version of Word?

With all that in mind, I thought I would be therapeutic to briefly summarise the main stages that I pass through when I am writing.

The dreaded introduction.

Undoubtedly my least  favourite part of writing. The uncertainty, the weight of expectation, the fear that you have forgotten how to do it. The enormously intimidating existing scholarship and the huge pile of primary material. The plan that made sense when you wrote it but which is now an undecipherable mass of crossed out paragraphs, arrows pointing to nowhere, and an obscene number of question marks. NB. This entire post could have been written just about this point.

favourite part of writing. The uncertainty, the weight of expectation, the fear that you have forgotten how to do it. The enormously intimidating existing scholarship and the huge pile of primary material. The plan that made sense when you wrote it but which is now an undecipherable mass of crossed out paragraphs, arrows pointing to nowhere, and an obscene number of question marks. NB. This entire post could have been written just about this point.

The false start.

Continuing the theme, the false start. You finally start getting something down, you pick your way through a particularly difficult bit of historiography, and you are feeling quite pleased with yourself. You stop for a cup of tea, and when you return, realise that you have 2,000 words of a 4,000 word paper, but you haven’t even mentioned the topic in the title yet. None of your 2,000 words are essential and most will need to be cut so you can actually address some of the important things. But the great news is: a false start is infinitely better than no start, and you can just deal with the editing later. NB. Save the original file because you might be able to use it somewhere else.

The comforting middle bit.

Before this post descends into paralysing misery, I usually find that once I get going, I tend to get into a groove and progress reasonably steadily. I generally target either a certain number of words each day (c. 1,000) or completion of a particular section from my plan. Attacking longer pieces of writing in bite sized chunks is essential and helps to make me feel accomplished every day, not just at the last. That said, there will inevitably be…

![Possibly blasphemously, I also fondly think of the darkest day as the Slough of Despond [William Blake, Frick Collection New York].](https://manyheadedmonster.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/william_blake_-_john_bunyan_-_cristian_reading_in_his_book_-_frick_collection_new_york.jpg?w=221&h=300)

Possibly blasphemously, I also fondly think of the darkest day as the Slough of Despond [William Blake, Frick Collection New York].

There are lots of reasons for the darkest day, that day when your muse deserts you, and writing simply does not happen, or progress is so slow that an outsider wouldn’t notice it. For me it is usually when I am tackling a bit that is tricky conceptually, or if I am trying to synthesise and reduce something rather complicated into a manageable and not too distracting size. After hours of furrowing my brows, picking up and putting down books, groaning, re-reading articles, chewing my fingernails, cutting, pasting, and standing up to look out of the window, I usually have something useable. That’s the moment I save those precious 300 words, put my whip down, and leave that dead horse alone.

The race for the finish.

Finally, your steed has miraculously revived, the wind is in your hair, and you are heading into the final straight! Everything is great. You have crossed out the majority of your plan, you have discarded all the boring and inessential parts, you have mastered that horrible bit about predestination. You are so excited about finishing you write two sections in one day. Your conclusion is so close you can smell it. Your examples are fitter, your jokey asides are funnier, your analogies more similar, and your argument more persuad-ier. It turns out that dreaded introduction was worth it after all. Now – to the pub*!

*It is important to celebrate your accomplishments, but please drink responsibly.

Measuring misery?

Brodie Waddell

In the late sixteenth century, the famed Elizabethan poor laws commanded every parish in the kingdom to relieve their poor residents though local taxation rather than private charity. By around 1800, England’s parishes were spending more than £4 million per year on poor relief.

One of my current research projects is an attempt to examine the nature of this massive expansion in formal, institutional support for the most vulnerable members of the community – that is to say, the rise of the so-called ‘parish welfare state’. I’ve been doing this by looking at the amounts spent by local officers – the overseers of the poor – in a set of sample parishes from across the country. Jonathan Healey at Oxford has been doing much the same, and we have recently decided to work together, combine our data and attempt to come up with a new analysis of this oft-noted development.

I will be discussing some of the early findings from this project at a talk on Friday, February 28th, at the Institute for Historical Research in London, so please do come along if you are interested. However, I thought I might offer one image from the talk here as I think it raises some potentially interesting questions.

What you see above is an estimate for national annual spending on poor relief based on my sample of 81 parishes. There are some significant methodological problems with these estimates – especially for the first few decades – that I will discuss in my talk. But, for the sake of argument, if we assume that this is actually an accurate measure of relief spending in England, the question then becomes: What does this tell us?

What you see above is an estimate for national annual spending on poor relief based on my sample of 81 parishes. There are some significant methodological problems with these estimates – especially for the first few decades – that I will discuss in my talk. But, for the sake of argument, if we assume that this is actually an accurate measure of relief spending in England, the question then becomes: What does this tell us?

It seems to tell us that there was not simply steady growth in relief in the 17th and 18th centuries. Instead, we see periods of extraordinary expansion, of stability and of retrenchment. We also seem to see a shift in the trajectory of the rise sometime in the decades around 1700, when growth seems to have accelerated markedly.

Yet, this graph is also extremely opaque. There is much that it does not tell us.

For example, what about non-parochial poor relief, such as formal charitable bequests or informal personal giving? Did this follow a similar pattern? Or was it working in the opposite direction?

What, too, about regional differences? Was there similar growth in sleepy country villages as in booming industrial towns?

Even more significantly, this graph tells us little about why parish welfare was expanding in this period. Although we can speculate based what we know about the periods of greatest expansion, the raw numbers in themselves cannot reveal short-term economic pressures or changing legal contexts.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, this bare line may obscure the nature of relief, which was after all a relationship between human beings who normally knew each other – not simply an anonymous financial transaction.

Did those who received relief actively demand it or passively accept it? Did those who distributed it do so gladly, grudgingly or fearfully – as an act of Christian charity, or out of mere legal obligation, or to stave of the threat of disorder? Was such relief considered the poor’s rightful entitlement? Or was it conditional upon their obedience and reputation for morality?

In other words, whilst this chart may offer a useful bird’s eye view of the emergence of perhaps the world’s first nation-wide welfare system, its lack of a human dimension may also actively mislead us about the nature of this system. For that, we must look to records in which real individuals – such as Mary Stevens, the 101-year-old vagrant – step out of the page to meet us.

Acknowledgements

The 81 sample parishes upon which the chart is based include 24 whose totals were generously provided by other historians. I am therefore very grateful to the late Joan Kent via Steve King (for 9 parishes), Henry French (7 parishes), Jeremy Boulton (3 parishes), Tim Hitchcock & Bob Shoemaker (2 parishes), John Broad (2 parishes) and Steve Hindle (1 parish). If you or any of your colleagues have data on parish poor relief before 1834 that you are willing to share, please get in touch!

Dead white men

Brodie Waddell

There has been rather a lot discussion on this blog of two pioneering historians: E.P. Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm.

For those of you who are keen to hear more about these two, I’d like to mention a couple of events that will be of interest. For those of you who are tired of me blathering on about dead white men, I can promise that both of these events are actually focused on the impact of Thompson and Hobsbawm’s ideas – rather than on the men themselves – and that after this post I’ll shut up about them for a while.

The first event was a panel on the legacy of Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963). The talks and discussion were recorded, and the podcasts are now freely available here. I believe the slides will also be available for download at some point soon.

There were three panellists. Professor Sander Gilman (Emory) focused on the ‘Englishness’ of The Making and the problematic place of Jews in this story. Professor Jane Humphries (Oxford) presented a wonderfully incisive look at the how the ‘sentimentalist’ and ‘pessimistic’ interpretation of the Industrial Revolution has been recently reinvigorated by rigorous quantitative research, including her own book on Childhood and Child Labour British Industrial Revolution (2011). Last, and definitely least, I expanded on some of the ideas that I had presented in my earlier piece on the future of ‘history from below’, drawing on the wider discussion in our online symposium, particularly the contributions from Mark Hailwood and Samantha Shave.

The second event I’d like to mention is the huge conference on ‘History after Hobsbawm’ that will be held at Birkbeck at the end of April. It’s going to be quite an occasion – I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many big-name ‘Munros’ from the world of history on a single programme. Although the event will partly be a celebration of Hobsbawm’s legacy, it also promises to be a forum for leading historians to tackle big issues such as nationalism, protest, class, environment, and so on. I won’t attempt to list all the speakers except to say that I’m particularly looking forward to the panels on ‘the crisis of the 17th century’ (Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Geoffrey Parker, John Elliott), on ‘Marxist and post-Marxist social history’ (Andy Wood, Jane Whittle, Lucy Robinson), and on ‘Frameworks of historical explanation’ (Peter Burke, Joanna Innes, Renaud Morieux). I hope to see some of you there.

The second event I’d like to mention is the huge conference on ‘History after Hobsbawm’ that will be held at Birkbeck at the end of April. It’s going to be quite an occasion – I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many big-name ‘Munros’ from the world of history on a single programme. Although the event will partly be a celebration of Hobsbawm’s legacy, it also promises to be a forum for leading historians to tackle big issues such as nationalism, protest, class, environment, and so on. I won’t attempt to list all the speakers except to say that I’m particularly looking forward to the panels on ‘the crisis of the 17th century’ (Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Geoffrey Parker, John Elliott), on ‘Marxist and post-Marxist social history’ (Andy Wood, Jane Whittle, Lucy Robinson), and on ‘Frameworks of historical explanation’ (Peter Burke, Joanna Innes, Renaud Morieux). I hope to see some of you there.